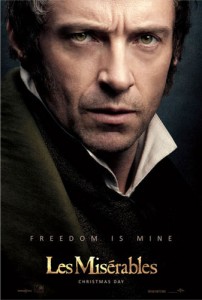

Hugh Jackman and Anne Hathaway are known for playing heroes on the silver screen – Jackman as Wolverine in the “X-Men” series, and Hathaway as the morally-challenged-but-trying-to-do-the-right-thing Selina Kyle in “The Dark Knight Rises.” It’s their current collaboration in the film adaptation of Broadway’s “Les Miserables,” however, that reflects faith and genuine heroic virtue in timely and timeless ways.

Hugh Jackman and Anne Hathaway are known for playing heroes on the silver screen – Jackman as Wolverine in the “X-Men” series, and Hathaway as the morally-challenged-but-trying-to-do-the-right-thing Selina Kyle in “The Dark Knight Rises.” It’s their current collaboration in the film adaptation of Broadway’s “Les Miserables,” however, that reflects faith and genuine heroic virtue in timely and timeless ways.

The night I saw a screening of the film (which opens Dec. 25) was the same day the story about New York City Police Officer Lawrence DePrimo buying socks and boots for a barefoot homeless man in Times Square went viral. Watching some of the selfless acts that took place in “Les Miserables” reminded me of that real-life situation.

That connection wasn’t lost on the film’s stars – Jackman (Jean Valjean), Hathaway (Fantine), Eddie Redmayne (Marius), Samantha Barks (Eponine) and Amanda Seyfried (Cosette) – who brought it up on their own at a press conference the following day.

Jackman described his character, Jean Valjean, as a quiet, humble hero like that police officer. He is a man who simply saw what needed to be done, then did it. Of course, Valjean’s journey to becoming that type of person lies at the heart of “Les Miserables.”

In the film, as in Victor Hugo’s original novel, Valjean is on the receiving end of a kindness that winds up changing his life. Prior to that, he is bitter and resentful after having been imprisoned and abused for 20 years for a minor crime. Then he’s given a second chance.

Jackman explains, “For me, Jean Valjean comes from a place of the greatest hardship that I could never imagine. And he manages to transform himself from the inside. Victor Hugo uses the word ‘transfiguration.’ It’s more than a transformation because he becomes more Godlike. It’s a religious or spiritual change, something that happens from within. To me, it’s one of the most beautiful journeys ever written. I didn’t take the responsibility of playing the role lightly.”

For her role as Fantine, the young mother forced to work as a prostitute in order to earn money to support her daughter, Anne Hathaway approached the character from a place of pain. Not just the pain of a 19th century character in France, but the agony of real women today who are victims of sexual slavery.

Hathaway said, “I read a lot of articles and watched news clips about sexual slavery. I came to the realization that I had been thinking of Fantine as someone who lives in the past, but she doesn’t. She’s living in New York City right now…So every day that I was her, I thought, ‘This isn’t an invention, this isn’t me acting. This is me honoring that this pain lives in this world, and I hope in all of our lifetimes we see it end.”

One woman she saw in a video clip had a particular effect on Hathaway and was, in fact, the person who influenced her characterization the most. She recalled, “She kept repeating, ‘I come from a good family. I come from a good family. We lost everything and I have children. So now I do this.’ She didn’t want to do this, but it was the only way her children were going to eat. Then she let out this sob like I’ve never heard before. And she raised her hand to her forehead, and it was the most despairing gesture I’ve ever seen. That was the moment I realized I wasn’t [just] playing a character; this woman deserves to have her voice heard. I needed to connect with that honesty and re-create that feeling. She’s nameless, I’ll never know who she is. She really was the one who made me understand why Fantine felt shame, what it’s like not just to go to a dark place, but to have fallen from a place where you didn’t think anything bad was ever going to happen to you – and the betrayal and rage you feel at life because you’ve gone through that.”

“Les Miserables,” of course, is ultimately a story of redemption and faith that may best be summarized by the popular lyric from the score, “To love another person is to see the face of God.”

Seyfried (Cosette) noted her belief that “Les Mis” has been such a phenomenon since the theatrical production premiered 27 years ago because the story reflects that ideal, because love “is what we’re left with at the end.”

Barks agreed because her character, Eponine, is a criminal who was raised by parents who, though comical in the film, are unscrupulous (played by Sacha Baron Cohen and Helena Bonham Carter). Eponine, therefore, never experienced love in its truest sense. But when she meets Marius (Redmayne), who is a “good man,” he stirs up the better angels in Eponine’s nature. Barks said, “In the end she does do the right thing because love has actually redeemed her.”

Redmayne was in awe of how the music behind that lyric was a thread that ran throughout the film, particularly in one scene where Valjean seeks sanctuary in a convent. He recalled, “You suddenly hear these nuns singing that piece, it’s suddenly a choral piece. And though Tom Hooper [the Director] has woven in religious imagery throughout the film, to suddenly hear this music in an ecclesiastical setting, something transcendental hit me in that moment.”

The transcendent ideal of seeing the face of God through loving another person wasn’t lost on Jackman either. Though the lyric was written for the musical, and is not a line from Victor Hugo’s original work, Jackman sees it as reflecting the message Hugo was trying to convey to members of the Church in 19th century France – a Church that Hugo believed had strayed from its founding principles resulting in extreme poverty, inequality, and feelings of abandonment by God.

Jackman explained, “For Victor Hugo, there’s a large comment in the book about the Church at the time. It made him very unpopular when he wrote it. It was the behemoth, powerful, distant, quite-excluding thing. There was a lot of fire and brimstone. I think he was reminding everyone at the time of Jesus Christ’s example, which is to love people.”

Though Hugo’s critique of the Church didn’t make it into the original Broadway show or the new film, the theme of Christ-like love is pervasive throughout. Jackman offers his own interpretation of the film’s message: “I don’t think you need to go to the top of a mountain in Tibet to find self-realization; you don’t necessarily need to do great things…The first thing to do is be present, know what you stand for and why, and face what is in front of you. As Anne reminded me this morning seeing that cop in Times Square, the humanity of just seeing what was required – that’s real love…That’s the answer to life.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Mercy, Love and Seeing the Face of God: A Review of “Les Miserables”