When I was younger, I remember watching the animated films All Dogs Go To Heaven and The Land Before Time. The themes and storytelling in both movies are quite terrifying, especially by today’s standards of family-friendly entertainment. What separates these films from even the darkest Disney movies is they shed light on things that are part of real life much more evidently – things like fear, pain, violence, suffering, evil and death. Nowadays, it seems like very few family films live up to the realism that is captured in most Don Bluth animated films. Although Pixar films seem to be the exception, movies geared towards children seem to be random, uninspired, slapstick, overly fluffy and focus more on the commercial entertainment value rather than reaching out to tug at the heartstrings of their viewers. Good art is hard to come by; and some of the best art seems to draw inspiration from endured hardship and makes you think deeply and forces you to reevaluate your perspective on life. I remember crying to my parents that I didn’t want my pet dog to die after watching All Dogs Go To Heaven. Then (SPOILER ALERT!) after watching a little, young dinosaur lose his mother in The Land Before Time, the realization that my parents are not going to be around forever was even more startling. The knowledge of the possibility of losing loved ones is something that shakes the very core of the adolescent mind.

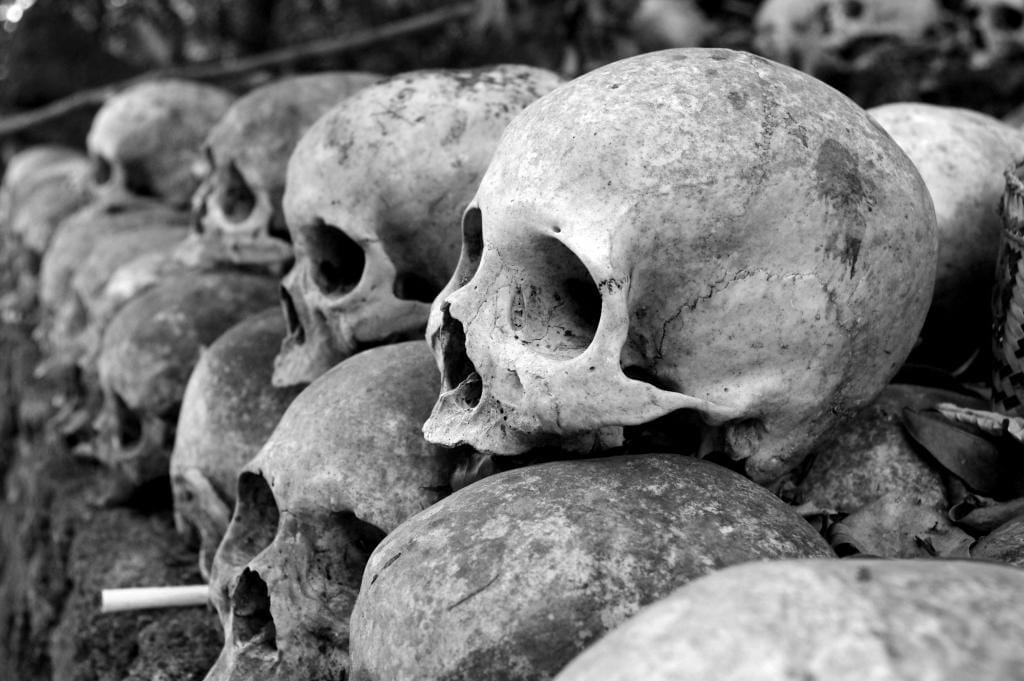

Death is such a strange thing to wrap our minds around. Subconsciously, we know it’s going to happen to us eventually, and we never know when our time on earth is up. It’s also easy to fear death because we have no idea what it’s like to cross that threshold. It’s that fear of the unknown that sometimes drives people to become overly zealous with nutrition, exercise, beautification and other forms of self-care. Old age and mortality are as inevitable as impending childbirth, yet many of us live as though it will never happen to us. It always comes as a slap in the face when we discover grey hairs, wrinkles, sore muscles and joints, or even sudden medical issues. It comes without saying that we ought to take good care of our bodies as the sacred temples they are.

But no matter how much organic food, vitamins, yoga or crossfit we fill our lives with, death will always be there waiting for us.

I experienced losing a family member for the first time when I was 7 years old. I remember how my grandpa and I used to make play-dough guns at the dinner table and he would tease me by poking my side with them while saying ‘PA-CHING!’ He also used to sit me on his lap and extend his dentures out of his mouth to rile me up, and I would try to grab them. Hearing he had passed away from heart failure seemed so unreal, especially right before Christmas. Realizing that he was not coming back was one of the most traumatic lessons I’ve had to experience as a child.

The second time I experienced a loss was when my dog died of old age. I was 15 years old at the time, and losing a pet whom I had grown up with was a difficult reality to grasp. I’ve had many fond memories of that dog, and it was easy for me to get choked-up every time I thought about it. Some relatives and friends from school would comment to me that he was just a dog, and upon hearing this I would get extremely angry. I get it that humans and animals aren’t created equal. But when you build a friendship with an animal after so many years, the value of that pet’s life to me seems to render the opinions of others as foreign cruelty.

Within a year of losing my dog, I lost my cousin as well as my other grandpa. My cousin was 22 when he lost his battle with cancer. My other grandpa had also been battling cancer in the last years of his life, but was taken by a stomach aneurysm after being released from the hospital. Losing both my cousin and my grandpa was still a shock to the system as though someone had reached into my chest and ripped out an artery. In the words of C.S. Lewis, “The death of a beloved is an amputation.”

One of my closest friends from high school had a brush with death after having a severe head injury at work. After finding out his emergency surgery was successful, I visited him at the hospital . When I saw him he was mostly high on painkillers, but I was so struck with grief I could not look at him in the eye. He had not lost his sense of humour though — most evidently after telling me to stop crying and suck it up. I was amazed at how such an accident should have killed him on the spot, and yet he managed to almost fully recover. Given he had hundreds of people praying for him throughout the country, his miraculous recovery was a testimony to me God really is real and answers prayer.

After bringing two little boys into the world, my wife and I experienced the most loss we had ever experienced within a span of 5 years. While the passing of her grandparents and uncle was one to be expected, losing her father had affected us the most deeply. Her uncle had been battling cancer for nearly two years and my father-in-law passed away within two months of being diagnosed with esophageal cancer. Although it was good we had the chance to say our goodbyes, what broke our hearts the most was the fact that our children would grow up without knowing their grandpa.

It seems once you enter a certain stage in your adult years, you begin to experience more funerals than weddings. Since my father-in-law’s passing, I attended a memorial for an old classmate from elementary school who had an accidental drug overdose. Even though we had not been close friends since we were young, his passing still caught me off guard. With every loss, it always comes as an initial shock and reminds us we are mere mortals with a finite existence on this terrestrial ball. As someone in my 30’s, knowing someone the same age as me had passed on was difficult to grasp. What makes it even more frightening is knowing how easy it is for life to slip away like a thief in the night.

The closest I have ever been to experiencing death, myself, was on my way to work when I was 21. I was driving down the highway during rush hour one January morning and I passed over a patch of black ice. I began to swerve back and fourth, and I tried to regain control of my ’91 Ranger. My truck started to spin out several times while hurdling 100 kilometers per hour uncontrollably. The drifting snow circulated all around and all I could see was a white shroud. I remember feeling like time began to stand still, and the first thought that ran through my mind was,

This is it. This is where my life ends.

The sense of having absolutely no control of what was going to happen next was so overwhelming that my heart sunk into my chest and I almost let go of the steering wheel. But then I felt my truck begin to slow down right down and the blowing snow all around me subsided. BANG! The front bumper of my truck hit a guard rail in the median of the divided highway just enough to halt the truck from moving any further. How I did not hit any of the surrounding vehicles when I initially spun out is beyond me. I quickly jumped out of the truck to see the damage, but my vehicle was the least of my worries. At that moment, a tow truck was exiting off the overpass close to where I had wiped out. It pulled over to the shoulder of the highway and the driver rolled the window down shouting,

“Holy s***! You have no idea how lucky you aren’t dead right now!”

The timing could not have been more perfect. Although the tow truck driver had to pull out two other vehicles from the ditch before helping me out, I attempted to drive myself out of the half-pipe until he came to rescue me. I was relieved, yet completely taken aback that I had managed to walk away from such a wipe-out with only a dented bumper.

Even as a person of faith, as nice as it is to believe in the afterlife, there are always those questions that linger in my mind — what if I’m wrong? What if this supposed relationship I have with God is an example of me only convincing myself that I have a unique place in this universe? What if there is no God, and the end of my life truly is the absolute end and there is only nothingness? Why continue living moralistically for myself and others if there are no eternal consequences? Why bother living at all if everything is vanity and utterly meaningless? The only good answer I have to these questions is, I would rather live my life as though there were a God and find out in the end there is none than to live as though there is no God and discover that He exists after all.

In my observation as a converted Christian, one of the biggest concerns people seem to have is whether or not a person has faith in Jesus. I will openly say that having faith is something that personally gives me a reason to keep living. There is something truly human about putting our hope in something mysterious that is infinitely larger than ourselves. But what I find most disturbing is when fellow Christians make assumptions about other non-religious people when their lives come to an end. Sometimes people who are religious or spiritual tend to come across quite arrogantly to others who might not share the same views on life. But on the flip-side, I’m sure my ill-thought out actions or words have caused similar hurt to others as well.

The problem I’ve noticed with how many Christians treat people who are non-religious is it seems like the only reason they build relationships with people outside of their religion is because they hope they will one day ‘accept Christ’ or covert to their ideologies. This isn’t to say that we ought not to be open about our faith. But I’ve noticed in almost every denomination I’ve associated with that churchgoers tend to favour to their own members as opposed to people outside of their denominational circles, or even family cliques. Should having faith give a person entitlement to be treated differently as a human being? Absolutely not! Evangelism should be more about caring for the lives around us as opposed to collecting butts in the pews.

If following Christ requires us to offer ourselves as living sacrifices to each other, we ought to do good to one another — not just out of a love for God, but also for the sake of putting others ahead of ourselves. Being kind to one another does not require us to compromise our values or our love for God, but much rather means respecting others without expecting them to submit to our beliefs. When any of our neighbors experience a loss, we should be standing in solidarity with them.

Do we ever stop thinking about our friends and family after they pass away? I like to believe that, after I die, I will get to see all my deceased relatives and friends once again. As a former Evangelical, I once believed that prayers for the dead were utterly pointless, as most would point out from the Bible that people are destined to die once and then face judgement (Hebrews 9:27). But one of the reasons why I’ve embraced praying for those who have died is because it really isn’t anyone’s job on earth to determine the final destination of any deceased person, Christian or not. If God is all-knowing, all-powerful and omnipresent, why wouldn’t He hear my prayers for the dead? Wouldn’t He know their hearts better than we know our own? If we are limited to what we can pray for, then wouldn’t this render God to be limited as well? C.S. Lewis, an Anglican-Protestant apologist had a surprisingly Catholic perspective on this particular subject,

“If, as I can’t help suspecting, the dead also feel the pains of separation (and this may be one of their pugatorial sufferings), then for both lovers, and for all pairs of lovers without exception, bereavement is a universal and integral part of our experience of love.”

— A Grief Observed, chapter 1

“Of course I pray for the dead. The action is so spontaneous, so all but inevitable, that only the most compulsive theological case against it would deter me. And I hardly know how the rest of my prayers would survive if those for the dead were forbidden. At our age the majority of those we love best are dead. What sort of intercourse with God could I have if what I love best were unmentionable to Him?”

— Letters To Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, chapter 20

One of the things I wanted to point out in this article is how, despite our differences in worldviews, we all share a common humanity. We were all conceived in our mother’s wombs, born into this world as infants, and we will all leave the world whenever our time is due. At the beginning of Lent on Ash Wednesday, people are usually marked with the ashes of blessed palms on their foreheads as a reminder of this profound truth. We are formed from the dust of the earth, and to dust we will return.

People are more valuable than ideology. This doesn’t mean we ought to disregard our religious beliefs to appeal to the masses, but sometimes sweating over the little details is not worth ruining relationships over. We ought to do good to everyone unconditionally — and if that leads more people to love Jesus by doing so, then fantastic! Having a relationship with Christ should mean loving our neighbors as well as our enemies. But if it involves valuing the rules more than we value people, then I would say it’s not an authentic relationship. This is where I understand why so many people have a huge disdain towards religion, and rightfully so.

We ought to love and be kind to one another, not because of whether or not we will suffer eternal consequences if we don’t, but because putting others ahead of ourselves is the most human and Christlike thing we can do.

Our time on earth is fleeting, and how we treat others is how we will be remembered. So, in turn, we must remember that death is always waiting.