As a Caucasian, I cannot speak for the experiences of my fellow humans who happen to have suffered oppression due to racism, but I hope I can offer my platform as an opportunity to share my observations with a healthy dose of nuance while simultaneously acknowledging those who have been victimized. A common phrase that is loosely tossed around nowadays is, “Check your privilege!” Anytime we are approached with such a direct phrase we are often overwhelmed with a sense of discomfort, followed by a knee-jerk, fight-or-flight reaction. With this in mind, I think it’s worth asking ourselves, “What exactly is privilege?”

It’s worth pointing out that privilege doesn’t even have to be limited to the context of race, ethnicity or gender. Privilege can come in a variety of forms and sometimes in a passive-aggressive manner. When I converted to Evangelical Protestantism as I neared adulthood, I was warmly welcomed into my new church community by the friends who have led me to faith in Christ, but I later discovered an underlying clique that was rarely addressed within the culture of my former denomination. Many of those who were longtime members of the congregation were connected either through blood-relation or by marriage. With that comes an underlying favoritism among people who are ‘family’ over those who may be newcomers or recent converts — especially when it comes to who becomes ordained or involved as volunteers, leaders, staff, pastors or elders. But to be fair, sometimes it’s just easier to approach people who you are already comfortable with, especially considering how involvement at a local church is sure to keep someone extremely busy. Though that always comes at the expense of excluding someone else for the sake of convenience or comfort.

I think what makes racism such a difficult and emotionally-charged topic to talk about is it’s extremely uncomfortable. It’s easier to put off, ignore or avoid an issue as opposed to tackling it head-on. And the longer an issue goes unaddressed, the longer it festers. In the wake of two recent events in the United States (one being the shooting of Ahmaud Arbery, the other being an incident where a white cop knelt on George Floyd’s neck causing him to die of asphyxiation), the widespread protests that have suddenly exploded is undoubtedly the result of a recurring problem that has been dismissed for far too long. The travesty of the loss of life ought to be a non-partisan issue, but I think the reason why racism is such an emotionally-charged topic is because it cuts close to the very core of our identity as humans.

To give an example of systemic racism from my own observations, the majority of the people I’ve grown up with in my rural Albertan hometown were of French-Canadian descent like myself (with the exception of a few Ukrainian folk). Mostly everyone attended Catholic Mass at the same parish, but I noticed whenever a newcomer was present (usually someone of Aboriginal descent), there was often tension in the air among my fellow parishioners as they would whisper to each other, “What are THEY doing here?!” Even while attending school in our rural small town community, it wasn’t uncommon to hear racial slurs among my peers — and it pains me to admit that I have partaken in such talk without realizing at the time what the gravity of racism really was. One of my best friends in junior high was of Lebanese descent and everyone used to nickname him ‘Tido’ because he reminded someone of a fictional Mexican character of some sort (which only shows the gross ignorance of living in a predominantly sheltered white community). It wasn’t until after high school that he told me he never liked the name, and all that time I had no idea.

In Canada, racially motivated persecution has happened for years and is reportedly on the rise. The residential schools controversy is a dark chapter in the history of the Church and the nation. I’ve also personally known guys I went to high school with who had later become cops and would brag about “the native guys” they pulled over for speeding and arrested simply because they talked back. One of these former friends who became a cop openly said, “How do you not become racist after spending time with these people?” On the other hand, I have other cop friends who are genuinely amazing people. Many policemen and public servants deal with trauma, substance abuse and depression because they deal with the darkest corners of society on a frequent basis. Many people who support the riots who aren’t involved seem to forget that, and that’s one of the reasons why I’m not anti-cop.

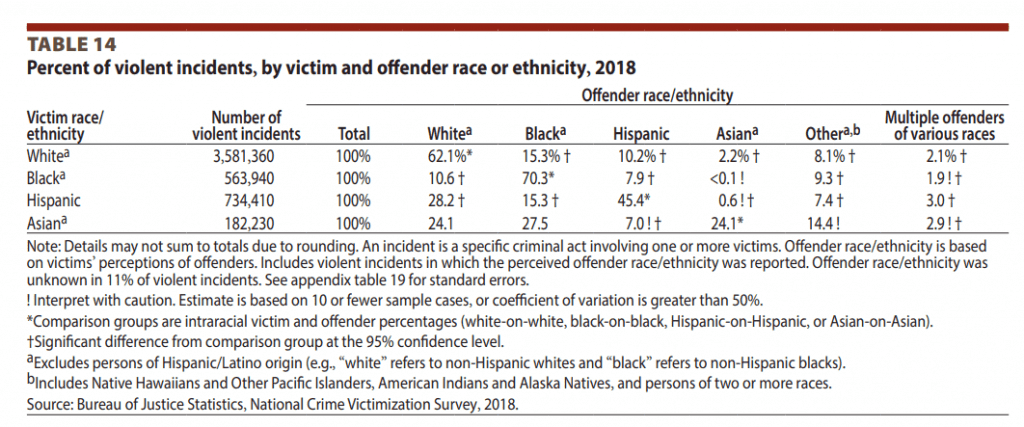

In the statistics above, it is shown that the number of violent incidents in the United States seem to be more predominant between persons of their own race. This could be because many incidents such as domestic violence usually happen between people who know each other. I guess the reason why I bring up these statistics is not to compare numbers, but to emphasize that the black community is a minority in a predominantly white demographic. This could arguably explain why black victims are seemingly low percentage in comparison to white victims. One could even argue that the higher percentage of whites victimized by blacks could be due to radicalized behavior due to frequent exposure to prejudice.

The loss of life among white-against-white or black-on-black incidents is undoubtedly tragic. But anytime we hear about a death, most people with a sense of social tact wouldn’t say to the deceased’s friends and family, “I’m sorry for your loss, but what about THIS person who died? Do you not care about them?” This is a textbook example of whataboutism that is similarly tossed between pro-choice and pro-life advocates as though mourning the loss of victims of mass shootings somehow invalidates the thousands of unborn babies killed in abortions.

I have often heard people respond to the pro-life movement by saying that it’s not enough to be anti-abortion, but one needs to be anti-rape, anti-abuse, pro-autonomy and pro-woman. There is not a single pro-life person I’ve met who would disagree with this. With every activist cause, there are always peripheral issues to be aware of while simultaneously focusing on the main issue. Regarding systemic racism, it is not enough to say that we are not racist. We have to be ANTI-racist. We have to be proactive at setting the tone of our culture to tangibly prove we are accepting, unbiased and sensitive to how our words and actions can dehumanize others, as well as being open to correction.

I think one of the reasons why people on social media have used the hashtag #AllLivesMatter in response to #BlackLivesMatter is because they feel as though a minority is being elevated over everyone else — but that shouldn’t be the case. All human lives truly do matter in a sense that every human being has inherent value and are made in the image of God. This would indisputably include black lives. I think the Parable of the Lost Sheep in the Gospel describes what ought to be the heart of a movement that recognizes that black lives truly matter.

“What do you think? If a man has a hundred sheep, and one of them has gone astray, does he not leave the ninety-nine on the hills and go in search of the one that went astray? And if he finds it, truly, I say to you, he rejoices over it more than over the ninety-nine that never went astray. So it is not the will of my Father who is in heaven that one of these little ones should perish.”

— Matthew 18:12-14 RSV

Oddly enough, the topic of racial discrimination can also be compared to Christian persecution. I’m not talking about the persecution complex many sheltered North American Christians seem to withhold, but the actual kidnapping, torture and genocide of Christians who happen to be a minority in certain parts of Africa and the Middle-East. As North Americans, the thought of being targeted specifically for having a Christian faith is a surreal thought — and most of us wouldn’t know how we would act unless it actually happened to us. In the case of systemic racism, I think this is another way to put racial injustice into perspective — especially considering many black Americans happen to be Christians. Imagine being targeted with violence, but instead of it being for your religious beliefs it’s the color of your skin. Or both.

As a white male, I think I have a responsibility to be in solidarity with victims of injustice. But if my skin color disqualifies me from having a valid opinion about an injustice, then that is the very definition of racism. Privilege has nothing to do with whether racism is less acceptable from a majority. It’s either wrong in every context or it isn’t. And there will always be someone ready to label you as an awful human being — simply because they don’t agree over the semantics of fighting an injustice. This is the sort of gaslighting that further embitters people to continue projecting their harmful prejudices they are being called out for. People don’t respond well to being told they are complicit to another group’s genocide by simply existing as white. This is akin to saying their worth as a human being is based on whatever flesh-vessel they happened to be born in. To an extreme, this can be interpreted as though they are better off dead. Because this is often referred to as ‘reverse-racism,’ some activists would call this a form of projecting internalized racism. Ergo, people need to let go of the absurd idea of “living your own truth” as though it’s some kind of novel, profound epiphany. The gods in Ancient Greek mythology certainly lived their own truth — and they were in perpetual competition with one another to the point of killing each other and their offspring. This is why moral relativism does not work, and why weaponizing privilege or victimhood is not motivated by a sense of true justice. It enables people to establish themselves as gods or goddesses while using their own moral constructs to assert power over others for the sake of their egoism. This is arguably among one of the contributing factors that has led us as a society to this point. I would dare say that many of those who were once abused by others are capable of becoming abusers themselves, and no human being is immune to evolving from victim to oppressor. This is where I think everyone has the right to draw a line in the sand and establish boundaries from such toxic people.

In the midst of the protests, especially with the rise of violence and looting, it is perfectly valid to feel threatened. As a white person, it is not ‘racist’ to be concerned for the safety of yourself, your family and friends and your community. A peaceful protest by definition should not put the well-being of others at risk, and unfortunately there are many who would use such opportunities to take advantage of a situation by vandalizing property and physically assaulting others. Paired with the amount of cops who have abused the system, this is the result of human nature at its worst. George Floyd’s fiance and brother have personally called for an end to the violence since rioting will not bring him back to life. If partaking in a protest means destroying the livelihoods of others (including other people of color) and putting their lives in danger, then that automatically puts into question whether the motives of such a movement would be considered morally justifiable.

If we take the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. seriously, it should come without saying that any form of racism should be called out. But in the context of our own culture here in North America, I think everyone has since forgotten its meaning. It is no longer a quest for equality and justice, but a will to power. No amount of virtue-signalling, yelling, protesting or “research” will make someone an anti-racist if rage or vengeance is the only thing that motivates them. The best thing one can do to fight racism is to see and acknowledge the inherent value that dwells in everyone who is different from you, and to exercise kindness, compassion, prudence and consideration in every conversation you have with them.

The killings of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd, the violence perpetuated by corrupt police, the systemic racism that has led to the riots reveal the same truth about humanity: we have all sinned. We all have done our part in the injustices that hurt minorities and intensify resentment towards the privileged and it will continue as long as we think there are no consequences for our actions or anyone larger than ourselves to answer to.

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

— Martin Luther King, Jr.