The best religious novelist of our time isn’t, as far as I know, a Christian believer. J.M. Coetzee completed his doctoral dissertation upon another Christ-haunted writer Samuel Beckett. He also is clearly influenced by the philosophical and theological writings of the Catholic (other than Bruno Latour) most-discussed in the secular academe. Of course, I’m talking about René Girard, whose work I’ve alluded to elsewhere.

Coetzee did attend a Catholic high school, plus he has both Dutch and Polish ancestry. Poland was not always the Catholic stronghold it is nowadays–Poles can thank the Germans, Russians, and the Jesuits for that. Actually, during the 16th century Poland was home to not only nearly all the Jews expelled from the West, but also of the Radical Reformation (so perhaps Coetzee has radical Calvinist or Unitarian roots?). In fact, it’s the only place where the Jesuits were successful at combating the Reformation. As the old joke goes:

Q: What is similar about the Jesuit and Dominican Orders?

A: Well, they were both founded by Spaniards, St. Dominic for the Dominicans, and St. Ignatius of Loyola for the Jesuits.

They were also both founded to combat heresy: the Dominicans to fight the Albigensians, and the Jesuits to fight the Protestants.

Q: What is different about the Jesuit and Dominican Orders?

A: Well, have you met any Albigensians lately?

WHERE WAS I? In my mind J.M. Coetzee is the greatest Christian (why not Catholic?) novelist of our time, because his characters constantly mull over the significance and practices of Christianity. They make the Incarnation strange again by inviting the unsuspecting reader to look at it from new angles. But don’t let me be the judge; judge yourself.

Let’s start with a passage from Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. I’m almost certain the passages you’ll read from Coetzee later are a polemic against this great German modernist writer. The Magic Mountain is a prime example of post-Christian attachment to an idealized Greece, even if some of the rough edges are briefly highlighted, instead of totally glossed over. The oneric section of the “Snow” chapter begins with the idealized beauty we usually associate with Greece:

“Youths were at work with horses, running hand on halter alongside their whinnying, head-tossing charges; pulling the refractory ones on a long rein, or else, seated bareback, striking the flanks of their mounts with naked heels, to drive them into the sea. The muscles of the riders’ backs played beneath the sunbronzed skin, and their voices were enchanting beyond words as they shouted to each other or to their steeds. A little bay ran deep into the coast line, mirroring the shore as does a mountain lake; about it girls were dancing. One of them sat with her back toward him, so that her neck, and the hair drawn to a knot above it smote him with loveliness. She sat with her feet in a depression of the rock, and played on a shepherd’s pipe, her eyes roving above the stops to her companions, as in long, wide garments, smiling, with outstretched arms, alone, or in pairs swaying gently toward each other, they moved in the paces of the dance. Behind the flute-player—she too was white-clad, and her back was long and slender, laterally rounded by the movement of her arms—other maidens were sitting, or standing entwined to watch the dance, and quietly talking. Beyond them still, young men were practising archery. Lovely and pleasant it was to see the older ones show the younger, curly-locked novices, how to span the bow and take aim; draw with them, and laughing support them staggering back from the push of the arrow as it leaped from the bow. Others were fishing, lying prone on a jut of rock, waggling one leg in the air, holding the line out over the water, approaching their heads in talk. Others sat straining forward to fling the bait far out. A ship, with mast and yards, lying high out of the tide, was being eased, shoved,and steadied into the sea. Children played and exulted among the breaking waves . . .”

Mann briefly spoils the lazy dream with the nightmare of homo necans we usually ignore:

“Scarcely daring to venture, but following an inner compulsion, he passed behind the statuary, and through the double row of columns beyond. The bronze door of the sanctuary stood open, and the poor soul’s knees all but gave way beneath him at the sight within. Two grey old women, witchlike, with hanging breasts and dugs of fingerlength, were busy there, between flaming braziers, most horribly. They were dismembering a child. In dreadful silence they tore it apart with their bare hands—Hans Castorp saw the bright hair blood-smeared—and cracked the tender bones between their jaws, their dreadful lips dripped blood. An icy coldness held him. He would have covered his eyes and fled, but could not.”

In the end Mann doesn’t let Castorp entirely forget the horror of the temple, yet he represses into an inarticulate muteness of a “silent recognition.” With that the novelist still makes his character side with the myth of Greek balance and beauty even if he couches it in a decidedly Christian rhetoric of love:

“Death and love—no, I cannot make a poem of them, they don’t go together. Love stands opposed to death. It is love, not reason, that is stronger than death. Only love, not reason, gives sweet thoughts. And from love and sweetness alone can form come: form and civilization, friendly, enlightened, beautiful human intercourse—always in silent recognition of the bloodsacrifice. Ah, yes, it is well and truly dreamed. I have taken stock. I will remember. I will keep faith with death in my heart, yet well remember that faith with death and the dead is evil, is hostile to humankind, so soon as we give it power over thought and action. For the sake of goodness and love, man shall let death have no sovereignty over his thoughts. And with this—I awake. For I have dreamed it out to the end, I have come to my goal.”

I immediately thought of these passages passage from Mann when reading “The Humanities in Africa” chapter in Coetzee’s novel Elizabeth Costello. Bridget, the sister of the title character, is a nun and she has the following to say about our (unhealthy) obsession with Greece:

“‘You miss my point, Elizabeth. Hellenism was an alternative. Poor as it may have been, Hellas was the one alternative to the Christian vision that humanism was able to offer. To Greek society–an utterly idealized picture of Greek society, but how were ordinary folk to know that?–they could point and say, Behold, that is how we should live–not in the hereafter but in the here and now! Hellas: half-naked men, their breasts gleaming with olive oil, sitting on the temple steps discoursing about the good and the true, while in the background lithe-limbed boys wrestle and a herd of goats contentedly grazes. Free minds in free bodies. More than an idealized picture: a dream, a delusion.”

Bridget continues, refuses a merely “silent recognition,” and takes poor Elizabeth behind another woodshed:

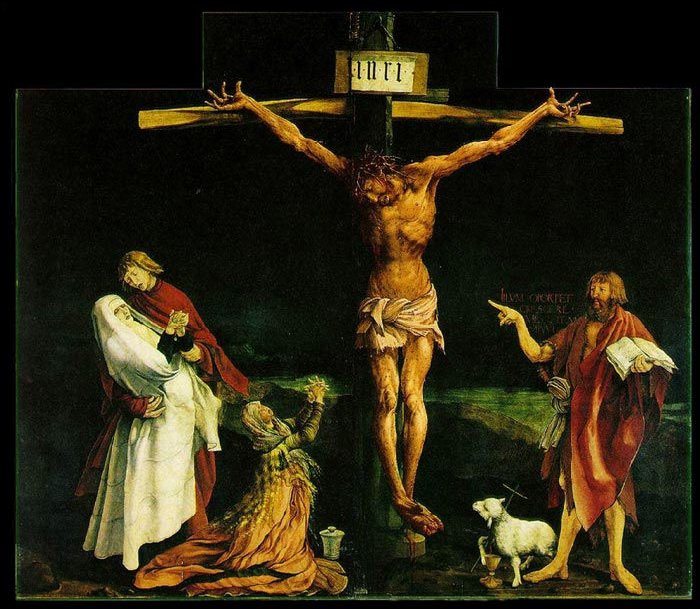

‘Do you think, Elizabeth, that the Greeks are utterly foreign to Zululand? I tell you again, if you will not listen to me, at least have the decency to listen to Joseph. Do you think that Joseph carves suffering Jesus because he does not know better, that if you took Joseph on a tour around the Louvre his eyes would be opened and he would set about carving, for the benefit of his people, naked women preening themselves, or men flexing their muscles? Are you aware that when Europeans first came in contact with the Zulus, educated Europeans, men from England with public-school educations behind them, they thought they had rediscovered the Greeks? They said so quite explicitly. They took out their sketch blocks and drew sketches in which Zulu warriors with their spears and their clubs and their shields are shown in exactly the same attitudes, with exactly the same physical proportions, as the Hectors and Achilles we see in nineteenth-century illustrations of the Iliad, except that their skins are dusky. Well-formed limbs, skimpy clothes, a proud bearing, formal manners, martial virtues–it was all here! Sparta in Africa: that is what they thought they had found. For decades those same ex-public schoolboys, with their romantic idea of Greek antiquity, administered Zululand on behalf of the Crown. They wanted Zululand to be Sparta. They wanted the Zulus to be Greeks. So to Joseph and his father and his grandfather the Greeks are not a remote foreign tribe at all. They were offered the Greeks, by their new rulers, as a model of the kind of people they ought to be and could be. They were offered the Greeks and they rejected them. Instead, they looked elsewhere in the Mediterranean world. They chose to be Christians, followers of the living Christ. Joseph has chosen Jesus as his model. Speak to him. He will tell you.’

How do post-colonial departments digest mysteries such as this one? One is reminded of the divisive rhetoric emerging from deep geographical divisions within the Anglican communion. These insights also square with Girard’s repeated claim that the victim is the only universal category everyone agrees to in our age. What’s more, the victim, as Nietzsche knew (and despised), is a Christian category first articulated by St. Paul and the Gospels. It would have never struck the Greeks to put something as ugly as that at the center of their world. Finally, Coetzee goes beyond scratching the surface with novels built around characters who are victimizers. He presses the issue of forgiveness in extremis, with characters who might be as despicable as Kermit Gosnell or George Zimmerman are to some, in novels such as Waiting for the Barbarians and Disgrace.

All in all, it’s because of sharp observations such as these, because of a novelistic intensity unmatched since Dostoevsky, that Coetzee is the most significant living writer of theological fiction. This is also why I couldn’t wait until the American release of The Childhood of Jesus and bought myself the UK edition.