Artur Mrówczyński-Van Allen is director of the Slavic Department at the International Center for the Study of the Christian Orient in Granada, Spain. He is Currently Professor at the Instituto de Filosofía “Edith Stein” and the Instituto de Teología “Lumen Gentium” (Granada), where he teaches Philosophy of History and Political Philosophy.

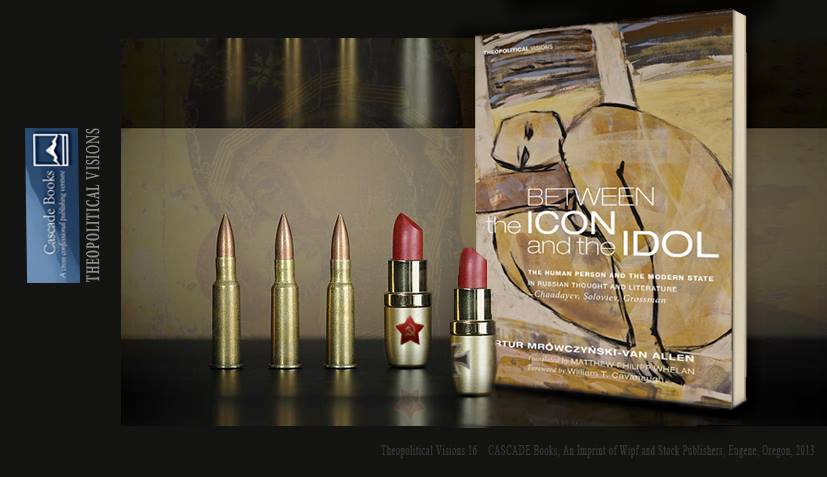

He also has a remarkable new book out entitled Between the Iconand the Idol from the Cascade imprint at Wipf and Stock.

Take a look at an excerpt from the introduction to Between the Icon and the Idol by renowned theologian William T. Cavanaugh (no stranger to Cosmos the in Lost) before you sample the book itself in a bit:

“The totalitarian state clearly intends to eliminate all those forms of organic community that rival the absolute loyalty of the individual to the state. This god is a jealous god. . . . Mrowczynski-Van Allen’s diagnosis is therefore no less relevant after the fall of the Berlin Wall. And his proposed cure is no less salutary. He appeals to the work of Grossman and other voices from the East to oppose the idolatry of the deified self with the icon, which opens up a distance in which giving and forgiving can occur. Eastern voices are so helpful because they refuse to quarantine theological questions; the borders between theology, politics, and literature are fluid and porous, because they are all a part of an integrated life. The holism of totalitarianism must be opposed by another kind of holism that replaces the idol with the icon. At the same time, the aspiration of secularism to separate politics from theology, and power from love, must be opposed by a politics based on an opening of human persons to God and to each other, the kind of self-donation found in Grossman, and for Christians, on the Cross.”

Here an excerpt of the prologue from Between the Icon and the Idol that I found floating around web:

I saw the human face of God, and my soul has been saved.

I

In the corner facing the entrance to the main room, an icon presides over the house. In this way the oikos renders visible its membership and participation in the ekklesia. Like an icon set in the iconostasis of a church, the household icon likewise displays the ordinary interpenetration of what is sacred and what is human. It refuses the lie that the secular is the opposite of the divine.

Whenever we have occasion to enter one of these houses—these houses that, throughout Eastern Europe, are increasing in number—and bow before the icon, we worship the Creator who became a creature, taking flesh in the womb of the Virgin Mary. At the same time, we recognize our own vocation and nature as icon. Perhaps we could describe the whole history of the world, just as we could describe the local histories of our communities and our lives, as the discovery before what and before whom we have bowed. Perhaps we could describe these histories in terms of moments in which the awareness of our own nature as icon, created in the image and likeness of God, permits us to glimpse the plentitude of what is truly human, which was revealed to us in the Incarnate Word, and to see not only ourselves but others as icons.

The decision before what and before whom to bow therefore expresses both who we are and who others are for us. Perhaps this whole matter can be summarized in the question, do I bow before the icon or the idol? Or, to put it in more contemporary terms, are we citizens—that is, clients, consumers, or slaves—or are we children—that is, sons and daughters, and therefore free persons? Someone might argue that the choice may not be so stark, that intermediate solutions are possible, and so on. I confess, however, that I am not able to locate myself under the description “brother citizen.” So I simply choose “brother,” bowing before the True Icon, worshiping the Father.

II

The increasingly evident totalitarian character of the modern state raises the question of the state’s nature and origin. Many of history’s most eminent thinkers have addressed this issue, which is anything but abstract: from classic studies on the nature of the polis or civitas and the threat of tyranny, to modern and contemporary texts dedicated to the totalitarianisms of our recent past. The present work outlines a proposal for the interpretation of totalitarianism from within a tradition of Russian thought. It is a tradition that, having largely shielded itself from the influence of the philosophical principles that led to the emergence of modern totalitarianism, also suffered that totalitarianism directly. By rejecting the separation between supernatural and natural, or between religion and politics, this tradition of Russian philosophy facilitated a characteristic way of interpreting the modern world, as well as itself, known as the Russian Idea. The Russian Idea, especially as it found expression in Russian literature, was uniquely able to describe the drama of the modern human person under totalitarian rule. This mode of philosophical reflection was nurtured from the same sources as the Orthodox iconographic tradition. In this tradition, the icon is not some abstract aesthetic expression; rather, it reveals a specific way of being. It reveals, in other words, an ontology and an anthropology.

The present work arises from the desire to show not only the basic features of this mode of philosophical reflection and its roots within Russian culture, literature, and philosophy, but also the extraordinary ability of such reflection to generate a culture and a literature. Chapter 1 presents the genesis of Russian philosophy, focusing on Vladimir Odoevsky and on Peter Chaadayev, particularly the latter. Chapter 2 treats the Russian Idea, especially with reference to its most distinguished representative, Vladimir Soloviev. Chapter 3 journeys through the life and work of the twentieth-century Russian writer Vasily Grossman, who with absolute mastery and extraordinary wisdom interpreted the totalitarian nature of contemporary society and identified the idolatrous nature of the modern state. Over the course of these three chapters, we will look at this tradition of Russian thought in its philosophical, theological, and literary expressions in order to signal the possibility of rediscovering the human person’s identity as icon and the modern state as one of the many metamorphoses of the idol. Moreover, I hope to show that this tradition of Russian thought—the Russian Idea—uniquely identifies the idol of the state because it has been able to preserve a sense of the human person as icon, even in the work of authors who were not Christians, such as that of Vasily Grossman.”

I can’t wait to get my hands on a review copy of this book. It seems like the perfect companion, perhaps antidote, to Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands–the most acclaimed and spine-curdling book of the 2010-2011 publishing season.

While you’re at it, you might also want to take a peek at Paul Froese’s The Plot to Kill God: Findings from the Soviet Experiment in Secularization.

Finally, if you want to get an idea what’s at stake here then watch a version of the Snyder Bloodlands lecture I saw at the University of Washington courtesy of the Polish Studies Endowment Committee:

BOOKS MENTIONED IN THIS POST: