The writing of the last series of post has got me thinking about what I find so irritating about the notion of what’s been alternatively called a Tea Party Catholicism, a Neo-Conservative Catholicism, or a (classical) liberal Catholicism.

There’s plenty to be annoyed about besides the fact that these upstart movements subordinate the faith to an economic theory even at the cost of historical truth. Such maneuvers seem so bizarre after 2008, because that was when so many of us became aware that the predictive power, the correlation with reality, the scientific and predictive value of economics, is almost nil.

While attempting to come to terms with my irritation I ran across a long passage from Robert Inchausti’s Subversive Orthodoxy: Outlaws, Revolutionaries, and Other Christians in Disguise that explained it better than anything I could come up with.

It’s a book about the productive insights we can glean from the works of orthodox Christians who were both avant-garde and influenced the culture of modernity in Christian ways. This companion volume to The Ignorant Perfection of Ordinary People surveys thinkers such as Dostoevsky, Chesterton, Jack Kerouac, Dorothy Day, Wendell Berry, Marshall McLuhan, and Rene Girard.

Here is where Inchausti started to hit me hard. It was as if he was pilfering words straight off my brains. Instead of trying to rephrase it for you I’ll let him speak.

“Americans, in particular, have been the victims of a myth of national ‘exceptionalism,’ which has been used over and over again to promote policies that have the immediate impact of separating individuals from their land and capital. Between 1983 and 1998, the net worth of the top 1% grew by 42.2%, while the net worth of the bottom 40% dropped by 76.3%. In other words, the bottom 40% of the United States population lost three-fourths of their family wealth over the past twenty years[!].”

He continues on a wider, and even more depressing, scale:

“On a global scale the shift of capital into fewer and fewer hands has been even more pronounced. According to the 1999 United Nations Development Report, eighty countries have per capita incomes lower than they were a decade ago, and the assets of the world’s two hundred richest people total more than the combined assets of 41% of the world’s population–that’s more than the combined wealth of two billion people.”

Inchausti then goes on to cite a passage from Dorothy Day on Distributism and comments on it:

“Day remarked, ‘Under capitalism the many had not the opportunity of obtaining land and capital in any useful amount and were compelled by physical necessity to labor for the fortunate few who possessed these things. But the theory was all right. Distributists want to save the theory by bringing the practice in conformity with it.’ Widespread ownership of property is the only check democracies have against the centralized state and monopoly capitalism, the only social force powerful enough to support local government, preserve local traditions, and keep communities self-sufficient. Large-scale industrial economies work against human happiness by making everyone economically dependent on people and forces they don’t know and can’t control. And in our era of global markets, this situation is becoming even worse.”

He finally shifts into talking about worldliness and how libertarianism only makes the problem worse. Even though he wrote this in 2005 it not only mirrors what pope Francis has said about worldliness, but even cites one of the pope’s main inspirations, the novelist Leon Bloy:

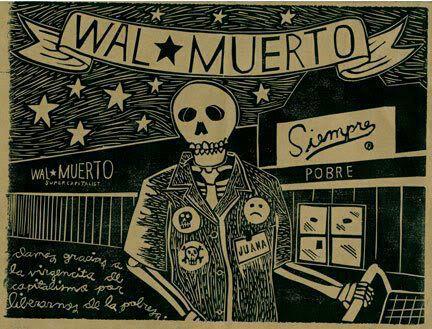

“In order to live with themselves, the rich–those lives built upon the industrial production of workers they never meet–require tokens of their personal entitlement, and this is accomplished through conspicuous consumption [think of the opening pages of Walker Percy’s Lost in the Cosmos] of rolling lawns, swimming pools, maids, gardens, and expensive sport coats. ‘Every man-of-the-world,’ Leon Bloy points out, ‘whether he knows it or not–bears in himself an absolute contempt for poverty, and such is the deep secret honor which is the cornerstone of oligarchies.’ Worldliness, in other words, is essentially the capacity to look past the unfair distribution of the world’s wealth in order to affirm one’s right to its spoils.”

In the next paragraph he makes a direct connection with the problematic aspects of Zmirak et al’s libertarianism and its illiberal consequences:

“This is why the lives of the wealthy so often narrow into a game of waxing and waning delusions of grandeur in which they identify the fate of their financial interests with the fate of civilization itself. And since they cannot imagine living in equality with those who must sell their labor on the job market they themselves have transcended, the rich tend to favor ‘no laws at all.’ The political philosophy of the wealthy is libertarianism, drifting more and more toward anarchy as their capital increases.”

This is why this Mitchell and Webb clip is perhaps not so funny after all: