The protests in the Ukraine have taken a somewhat unexpected violent turn recently after the promise of peace, reports Timothy, author of Bloodlands. What do these recent events tell us about the Church and about what God thinks about flags?

Tim Kelleher’s recent analysis of these events, “Crucifixion in Kiev,” makes three very important points about their theological significance. He looks at the events with Western eyes:

“To Western eyes, these blokes, of long beard and foreign vestiture, might seem eccentric.Who are they, why is their presence tolerated, and what are those things they carry?

As for who, they are the sacerdotal face of Ukraine’s major churches in the Orthodox tradition.What we mostly see them carrying are icons, the sacred images intrinsic to the Orthodox liturgical witness. Why has everything to do with who and what. For in Slavic culture, religion — particularly the experience of Orthodoxy — does not dwell on one side of an imagined wall never prescribed in that fruit of Magna Carta which are the American founding documents.”

The first point: The most recent readings of the wall separating church and state are spurious at best. Mark Sehat, in The Myth of American Religious Freedom, takes that wall apart. He not only argues that the wall has always been porous, but also that Protestant groups have dominated the political agenda even after the disestablishment of their churches on the state level.

Justin Tse makes an interesting parallel argument in his posts about what he calls the unraveling of the Protestant Private Consensus. You can read more about this notion here. I’ll definitely return to the Private Consensus in the coming weeks, because Justin will publish a guest post tomorrow engaging my widely circulated post about the structures of Protestant and Catholic sex scandals.

Second: The notion of a private theology is especially nonsensical, especially in liturgical traditions, even in countries hit as hard as the Ukraine by Soviet secularization efforts. Theology (like atheism or capitalism) makes claims upon one’s whole world. Scholars such as Brent Nongbri have even gone so far as taking apart the concept of “religion” understood as a private cleaving to religious sentiment that is cordoned off from the public square as a very recent development born of Protestant religious scholarship. In his book Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept he argues that before the rise of the notion of religion Christians, Jews, and Muslims didn’t see each other as belonging to different religions, but instead as heretics or idolaters from their own particular comprehensive worldview.

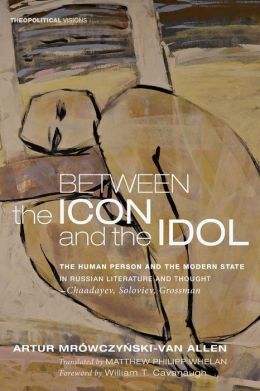

Within the Slavic Orthodox context, Artur Mrowczynski-Van Allen’s book Between the Icon and the Idol: The Person and the Modern State in Russian Literature and Thought demonstrates the public nature of theology by showing how Orthodox iconography influenced even secular Russian authors such as Grossman in their struggle against totalitarianism.

Finally, Kelleher’s important article highlights one of the perennial problems of Orthodoxy: its attachment to the nation-state.

“President Putin makes no secret of his view that Ukrainian independence is an illusion tolerated by Russia for as long as it serves the latter’s purposes. Further, capitalizing on the role of Orthodoxy mentioned earlier, he has found religious ‘justification’ for an expanded map of Russia. Invoking a revisionist image of ancient Kiev-Rus, modern borders ‘dissolve,’ giving way to a ‘deeper’, ‘truer’ identity — one that happens to be geographically broader.

This vision of a greater Russia was recently echoed by the Patriarch of Moscow, in an ominous warning that Russia would be obligated to intervene should the situation in Ukraine devolve into civil war. Indeed, over the past year, the Patriarch has led a parallel campaign for an ecclesial hegemony that would subsume all Ukrainian Orthodox under his authority. The presence in Maidan of priests from each of the Orthodox churches — including those within his jurisdiction — is a bright sign that the attempt is being thwarted.”

This reminds me of William T. Cavanaugh’s conundrum in Torture and Eucharist, about how after the collapse of the supra-national ties of the Corpus Mysticum it is difficult to envisage the church as the mystical body when one part of the body is constantly blowing off the legs or arms of another part in the service of the nation-state.

On a much more petty level, years ago the University of Washington was looking to hire a prominent Orthodox theologian–possibly John Meyendorff, I don’t remember–for their Comparative Religion department, but national politics stood in the way. The Greek Orthodox church across the Montlake Cut from the university just couldn’t countenance taking on a Russian Orthodox priest. The Russian Orthodox church was too far off downtown to be a practical solution.

So perhaps God does hate flags after all?

Yet, it is a sign of hope to hear from Athanasius McVay that some of the Orthodox priests we’ve seen in those dramatic pictures are actually under the jurisdiction of Moscow. They are putting their lives on the line to keep the peace. Couldn’t we use more of that?

With an icon and a newspaper in hand, current events should make us reflect upon the boundaries of theology. (All due apologies to Karl Barth).