When translating the book Socrates and Other Saints I learned that Erasmus, among others, called Socrates a saint.

How strange does that sound to your ear? It shouldn’t.

The notion of spiritual exercises was first developed by the Greek philosophers and only later taken up (and democratized) by Christian thinkers. Ignatius of Loyola came fairly late in this tradition. Actually, very late, his Spiritual Exercises were a recovery of the tradition of the spiritual exercises after it went mostly underground during the scholastic period.

A couple of weeks ago I wrote a piece, “Science Doesn’t Think,” taking up Damon Linker’s critique of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s philistinism. He was correct in pointing out how metaphysics precedes science in setting down the fundamental preconditions for our understanding anything.

But there was a flaw in his argument in the following passage:

Socrates appears to have been one of these natural philosophers in his youth. But at some point he became convinced that the anti-dogmatism of his fellow philosophers concealed an even deeper dogmatism. Like the poets, politicians, and craftsmen he regularly talked to on the streets of Athens, the natural philosophers were incapable of giving a coherent account of their own activity and why it was good. They couldn’t explain the nature and origins of the concepts they presupposed in their own thinking. They couldn’t consistently define what they meant by such fundamental ideas as truth, goodness, nobility, beauty, and justice. Neither could they consistently explain what they hoped for from the knowledge they so passionately pursued.

If the natural philosophers truly wished to liberate themselves from dogma in all of its forms and live lives of complete intellectual wakefulness and self-awareness, they would need to pose far more searching questions. They would need to begin reflecting on human nature as both a part of and distinct from the wider natural world. They would need to begin examining their own minds and motives, very much including their motives in taking up the pursuit of philosophical knowledge in the first place.

Philosophy rightly understood is the mind’s rigorous, open-ended, radically undogmatic pursuit of this self-knowledge.

This makes the Greeks look like ancient Voltaires pursuing knowledge for the sake of knowledge itself. But there was actually a fair share of dogmatism in their pursuits. What the philosophers wanted to do was to transform themselves, rather than merely endlessly continuing the questioning for the sake of questioning like analytical philosophers.

Linker’s description is also too disembodied. Dariusz Karlowicz in Socrates and Other Saints argues convincingly that Socrates, Plato, even Aristotle did much more than think freely. They adhered to a set of spiritual exercises that ranged from intellectual pursuits to gymnastics. The goal was transforming one’s whole being to be more in tune with the order of the cosmos.

This was done in philosophical schools. The followers of Socrates we see everywhere in texts about him are one such group. Much like monastic communities (the main Christian inheritors of this tradition) these groups had strict sets of rules about what activities, mental and physical, had to be performed in order to create a perfected human being. Apparently, if they were anonymous Christians, they didn’t much believe in irresistible grace!

These quasi monastic groups were so dogmatic about what exercises were best for furnishing the mind of a wise man that they spent a considerable amount of time debunking the words and deeds of the leaders of opposing schools. If their opponents could be exposed as shams, as not having learned how to die properly (like Socrates), then their school would be partially vindicated as being correct.

The ten volumes of The Lives of Eminent Philosophers by Diogenes Laertius are chock-full of amusing examples of mutual debunkings and accusations between schools. It also lists some of the exercises unique to each school. These were usually set down by an exemplary figure who gathered followers around himself, hence Saint Socrates. Furthermore, it was believed that martyrdom was the best way to attest to the truth of one’s teachings (or the founder of one’s school), because it showed that one is willing to pay the ultimate price for the teaching, and that they make one spiritually resilient enough to stand the ultimate test.

All of this assumed that there is a correct way of life that would give you penetrating epistemological insight, but, and this is a BIG BUT, only at the end of the road of repeating sayings of sages (basically prayer), fasting, exercise, and mastering math and other intellectual pursuits (not for their own sake, but for the sake of self-transformation).

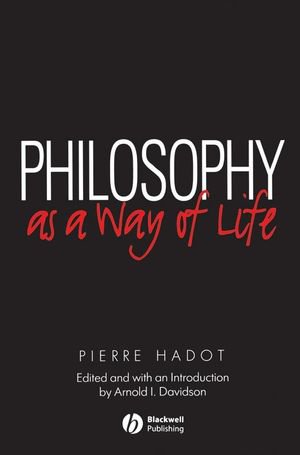

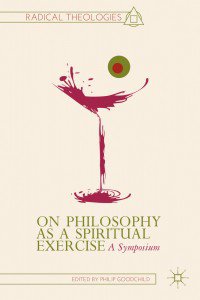

Recent philosophy and theology is tapping into this tradition after the groundbreaking work of Pierre Hadot recovered it. I’ve already written a little about Jean-Yves Lacoste’s From Theology to Theological Thinking. John Milbank’s Beyond Secular Order also discusses how ancient philosophy collapsed the boundaries between theology, philosophy, and life, but I haven’t gotten far enough in the book to see where he takes it. Milbank’s colleague at Nottingham has a whole book that revolves around holding a conversation with sources ancient and modern on philosophy as a way of life. It’s entitled On Philosophy as a Spiritual Exercise: A Symposium. A review copy of his book just arrived from the publishers yesterday and I can’t wait to dip into it whenever/if I find some free time in the coming weeks.

You can glimpse what Goodchild is up to in the following interview on the topic of spiritual exercises:

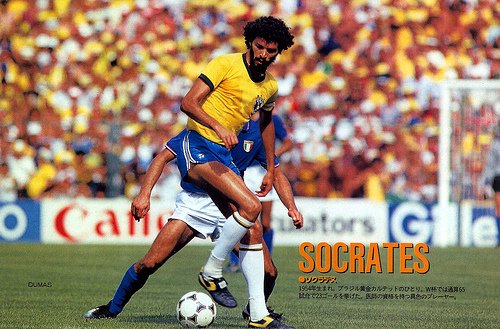

For good measure, here are the career highlights of the Brazilian soccer great Socrates:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XcqAD697Cbk

If I were properly philosophical I’d be reciting the Liturgy of the Hours instead of writing this post.