Easter is over, but there are plenty reasons to reason out the resurrections relation to reason.

The standard question is, “What does Athens have to do with Jerusalem–reason with revelation?” Lev Shestov’s (friend of Edith Stein’s teacher Husserl) Athens and Jerusalem is the most forceful presentation of the view that there’s nothing uniting the two.

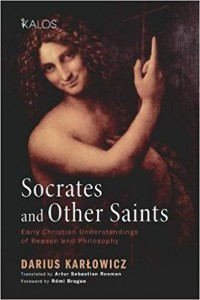

But not even the Ante-Nicene Father Tertullian, held this position, even though it is frequently attributed to him. If you want to be completely disabused of the commonplace that Tertullian was an irrationalist, then there is an extended discussion of Tertullian’s philosophical views and sources in the recently published book, Socrates and Other Saints, by Polish philosopher Dariusz Karlowicz.

The Catholic tradition has staunchly resisted such clean fideist breaks in its polemics against various Protestant groups ever since, actually, ever since the Reformation.

More recently Pope John Paul II’s On the Relationship Between Faith and Reason took this polemic one step further by opposing the Catholic position against an increasingly relativist late modernity. As a result, Catholicism, which is often singled out by glib commentators as being a motley collection of irrational traditionalists, is de facto the last defender of reason.

As it should be.

The philosopher Jean-Luc Marion lays down the deep historical connections between Athens and Jerusalem in his The Visible and the Revealed:

First, Christians themselves would have to begin by realizing that their faith cannot and must not in any way do without reason, even less pride itself on any lack of reason. Believing without reason actually comes down to scorning him in whom we claim to believe. This is so, first, because, as St. Peter underlines, we must be ‘‘ready to make a defense [απλγια] to anyone who demands an accounting [λγς] for the hope that is in’’ us (1 Peter 3:15). To believe without knowing how or what does not increase faith but leads it astray, maybe even ridicules it.

Those are strong words!

Marion continues:

The point of ‘‘giving an account’’ here actually is not to quarrel with the interlocutor face to face, as in an ideological battle, but to render justice to him in whom we say we believe, in him and in his high reason, for the believer will have to ‘‘give an account [απδωσυσιν λγν] to him who stands ready to judge the living and the dead’’ (1 Peter 4:5). We will have to answer to Christ for what we will have answered humans on his behalf and ‘‘for every careless word you utter, you will have to give an account [απδω-συσιν περι αυτυ λγν] on the day of judgment’’ (Matt. 12:36).What we will have said of Christ before humans, Christ will say of us before the Father.

Therefore, there is no space for fideism in the earliest Christian sources. If the account must be given, then that raises another set of questions about the relationship of finite reason to the infinity of God:

Immediately this raises another question: Why does God expect us to speak of him with arguments, reasons, and rationality? Does God not know better than any of us that we can neither comprehend him nor even reason correctly about him, without taking into consideration our fear before those who do not accept him? Yet if God is God, he knows all that and more; thus if he asks us to speak with reason, without doubt he has good reasons for asking it of us. What do we know about these reasons?

The Visible and the Revealed then brings in the death and resurrection of Christ into the whole discussion of reason and historical Christianity:

We know at least this: Christian religion announces the death and resurrection of a human being who was God and still is. This man Jesus Christ is called the Logos, the Word, and hence Reason. Even the paradox of his crucifixion, which contradicts ‘‘the wisdom of the world,’’ remains still a logos, ‘‘the logos of the cross,’’ which opposes a different sophia to the wisdom of the world, namely, the ‘‘wisdom of God’’ (1 Cor. 1:18–25). When St. Paul debates the Athenians on the Areopagus, it is in the name of the logos of him who by right carries the name of Logos. And when he announces the foolishness of the Cross against secular Corinthian culture, he still speaks according to a logos, because he speaks in the name of the Logos and according to the Logos. Even and especially when someone faithful to Christ confronts the rationality of the world, he or she confronts it with reasons and for the love of wisdom.

The fascinating thing about this is how much the Early Fathers trusted natural reason. In Socrates and Other Saints we learn that Tertullian, yes that very same Tertullian who’s wrongly considered to be the mad prince of the irrationalists, had an incredibly high view of natural reason:

The fascinating thing about this is how much the Early Fathers trusted natural reason. In Socrates and Other Saints we learn that Tertullian, yes that very same Tertullian who’s wrongly considered to be the mad prince of the irrationalists, had an incredibly high view of natural reason:

We will now return to The Soul’s Testimony. The analysis of further examples demonstrates their striking convergence with Christian teaching. The spontaneous utterances are treated as an expression of a natural knowledge that is present in the human soul, they confirm the identity of natural knowledge with the many truths revealed by the Creator. This is not only the case with regard to the existence of God. Tertullian says to the soul, “Nor is the nature of the God we declare unknown to thee.” Natural reason rejects the indifferent and non-salvific God of the philosophers for the living God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Against philosophy the soul confirms further truths of Christian teaching: the goodness, omnipotence, omniscience of God, and the anger that all human sin awakens in God; the soul knows of Satan’s tricks, it also knows of the Last Judgment, the possibility of either reward or punishment, or even the truth of the resurrection!

I suspect most of fully did not expect to see even the resurrection coming in that list. Is still surprises me when I read it.

Don’t Tertullian’s views sound surprisingly like Karl Rahner’s speculations about anonymous Christianity? Tertullian does complicate the natural knowledge of the soul (read Socrates and Other Saints for the full story), but it’s also true that Rahner’s teachings are a lot more complicated, traditional, and reasonable than he’s given credit.

I’ve mostly laid down the similarities between reason and revelation. I leave it to a future post will attempt to explore the logic of the resurrection in more detail. For now, the answer to this post’s title question is that Christianity, which owes its existence to the resurrection, helped to preserve reason.

In other words, Christianity saved reason (more than once).

Make sure you read up on Karl Rahner’s Biblical Notion of Anonymous Christianity.

Please also make a donation to this blog through the button on the upper right side of this page to help keep it going.

Stay in touch! Like Cosmos the in Lost on Facebook: