Rosman: One of the fears about practices of Silence is that they seem so contentless. You already pointed out some of its incarnational possibilities. Could you go further into what is unique, specific about Catholic practices of Silence?

Johnson: Well as I pointed out earlier, Silence is not contentless. It is content-full. What I hope is clear from my answers so far is that Silence/contemplation is really more about the shift from self-consciousness to a deeper engagement with reality. Your question gets at one of the issues here — the fear about the practices. Silence really is turning away from the tendency of our minds to measure and control and explain and define and it is this turning away from control that seems to be both attractive and disturbing. But so many are attracted.

An example of this attraction is mindfulness. Mindfulness is a trendy thing now and so many people have been exposed to the idea of just resting in what one is doing without thinking about it or talking to one’s self about it. That initial step of being mindful turns one in the right direction but ultimately one learns that one doesn’t have control about the Silence born there. Silence is a form of engagement and participation in the world that arises on its own. Trying to make Silence happen will stop Silence from arising. SIlence is ruled by The Paradox of Intention. In order for us to achieve the goal, one must give up the goal. Sleeping is a good example. If I “try to fall asleep”, I’m guaranteed to stay awake. So we are told to do things like relax, count sheep, bring our attention away from sleep and then sleep comes. It is the way our mind works. There are forms of consciousness that arise if one gets out of the way.

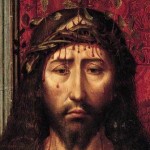

What is unique about “Catholic silence”? Well there is no such thing. Silence is Silence. Identity does not figure. Silence is a way our mind thinks/participates with reality. It is a type of thinking that we don’t control. It is receptive and sees the whole before we begin to analyze and label. An analogy I often use when talking to students is the analogy of taking a picture. Silence is the part of the mind that sees the whole thing — like when one snaps a landscape photo. But if someone asked you to describe the picture, you would have to describe it piecemeal — start in the upper left hand corner and explain what you see and in doing so you aren’t any longer also focused on the lower right hand corner. There is no way to describe both at once. One is then focused in a form of attention that is narrow and very linear. Definitions and identity are in this realm. But in Silence — it is the whole picture — it is the actual picture of the entire landscape — and this form of awareness has a larger attention that is not narrow and much more holistic. Traditional theology points this out. Cataphatic theology gives us the labels and words in talking about God. It is narrow and focused and helpful. Apophatic theology begins to move us away from this way of engaging reality by first negating labels. It begins us on the path of letting be but it can and must go even further if it wishes to shift past linear understanding and so apophasis has another level. There is a form of apophasis discussed in the tradition that negates even the negation. This is the paradox of intention at work. This is the move to Icon and Sacramentality. There is a shift in how language is used then. It becomes more mystagogical and less about definitions and labeling to understand. It is this form of engagement that ultimately allows us to drop labels and participate fully. It is an embodied and deeper way of knowing. It is how the human mind works.

So it is not like there is anything uniquely Catholic in Silence. But the interpretation of Silence is where identity comes to play again.

I would say what is unique in Catholic practices of silence is the Incarnation. The symbolic and the sacramental are also in many other traditions like Tibetan Buddhism for example but the focus on embodiment, on Incarnation of the divine as its main point of the tradition seems to be unique. The entire creedal assertions about the divine Incarnating in, through, and as Christ and the Church’s willing participating in that embodied Incarnation offers an interesting approach to engaging Silence.

Silence is not about running from the embodied world but actually running to it. This underlying assumption in Catholic theology is why the sacramental — why words, physical objects, sexuality, desire — can all be doorways to a becoming more “enfleshed”. It is the path of Christ, to allow self-giving love to take more and more physical form. The interpretation of Silence and the apophatic as world-denying and body-hating is a huge issue that keeps popping up in Christian circles and there are so many scholars and thinkers and practitioners who keep trying to clarify this for us. But this Incarnational aspect is why for instance one sees the Roman Catholic tradition holding together the sacraments, Silence, corporal works of mercy, and the ethical commands we find in Catholic Social Teaching. But I gnerally tend to think of Catholic in broader terms than just Roman Catholic and I see catholic Incarnational activities in the entire Christian tradition. And in fact, it is the sacramental and the Silence inherent in the sacramental that is being discussed in various non-Roman Catholic churches as demonstrated in Hans Boersma’s Heavenly Participation, or even more popular works like The Cloister Walk.

At the risk of going on too long, I wish to offer a few other points to flesh out the Incarnational aspects of Silence further. First, I think what people need to keep in mind is in this interview we are necessarily using a linear, logical type of abstraction to discuss something that cannot be articulated in those terms. As I stated above, silence is an actual practice. It is a type of thinking and way of knowing that cannot be quantified or defined with precision and so it appears contentless from within a linear/logical perspective but it is saturated with content once one shifts to the perspective of Silence.

Next, there is a danger of misunderstanding Silence and so that is why the focus of Silent practice is on intention. What is the aim of the silence? Where is one directed? This is why the idea of “purification” is an essential piece. To clarify the point of Silence, the beginning stages are confessional. For Christians the foundational path is penthos — compunction. Traditionally, in the early church, this was seen as the cornerstone for the building of the Temple of God. This stance is the birth of humility. Unfortunately the word compunction has shifted to mean in many circles as some sense of guilt in a negative and psychologically harmful way. But the idea originally was a laying down of power and control. A type of humility. It was a noticing of how we have missed the mark or cut ourselves off from God. And so the initial stages of Silence resulted in a weeping for ones sins. That sort of language is seen as problematic by many now for various reasons but I think if one keeps in mind that Silence is a shift from doing and controlling to being and not controlling, weeping can be seen as a form of surrender and acceptance. Maggie Ross’s book The Fountain and the Furnace gives a much deeper sense of this often misunderstood Christian teaching on tears.

A third thing to remember is that Silence is not silent. The word does not mean just external/exterior silence in the world. The word Silence I have been using is a very neutral word that can be used and understood by believers and non-believers alike. But Silence is just another word for the Christian practice of contemplation — a receptive way of “seeing God.” Another word one could use is beholding. It is the type of seeing that shifts the focus away from us as the subject doing the seeing to a space where my self-conscious experience drops away. You see and you are being seen at the same time. Who is the primary actor? One cannot say. It is a resting in God’s presence. Oftentimes the Song of Songs was used as a way of discussing this type of engagement with God. Our soul and God take on the role of the lovers in that scriptural book and the intimate and erotic language of the bridal chamber is a metaphor for the ecstatic type of knowing assumed here. I am not speaking of strange ecstatic experiences in a literal way but using language much more poetically and metaphorically to describe something quite ordinary. I’m pointing to the deep engagement with physical reality with an intention of reaching what has traditionally been called the transcendent through the immanent. In fact, it is in being silent, one turns to the world and discovers Christ deeply embedded there.

And it is this being present to the world in humility that self-giving love is born in us. Christ meets us in the flesh. This is the reason why we have the sacraments. They are ritualized and embodied actions that allow for participation. They make what they signify real but that sacramental vision assumes Silence. It assumes a form of knowing that is contemplative.