Dave Griffith is the author of A Good War Is Hard to Find: The Art of Violence in America and is the director of the creative writing program at Interlochen Center for the Arts. His essays and reviews have appeared in the Utne Reader, IMAGE Journal, Creative Nonfiction, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Paris Review online, among others. He has just finished a two-year stint as a Mullin Fellow at the University of Southern California’s Institute for Advanced Catholic Studies where he completed the manuscript Pyramid Scheme: Making Art and Being Broke in America. He lives in Michigan with his wife Jessica Griffith, author of the memoir Love And Salt.

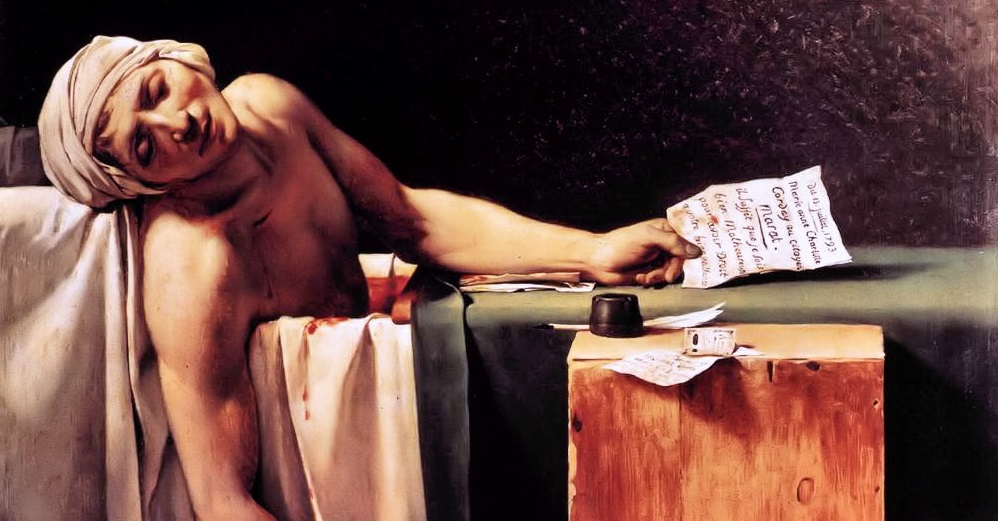

Artur Rosman: Your book A Good War is Hard to Find makes the shocking Abu Ghraib pictures the hub of its reflections. It borrows its title from a Flannery O’Connor short story that culminates in something like an act of revelatory violence. Does it make sense to speak of your book and Abu Ghraib in terms of revelatory violence? Do representations of violence bare, expose, something to us?

Dave Griffith: I suppose so. For O’Connor, violence got her characters’ attention–at least that’s what she said. She felt that it was the only thing that could get their attention because they were so often blinded by pride. She was very fond of Sophocles, so it makes sense that she conceived of violence functioning this way.

However, she’s writing fiction. This is one of the things I worried about when writing A Good War; that applying O’Connor’s poetics, so to speak, to an actual event was somehow shortsighted or naive–an English major trick that wouldn’t hold up under scrutiny.

But, the book has been out in the world for some time now and people keep reading it, and referencing it, and returning to it, so I think applying O’Connor’s understanding of violence and sentimentality (an arrival at a mock state of innocence that strongly suggests its opposite) to the Abu Ghraib photos really helped people have a conversation about not just how they felt about the photos and what they appear to depict, but what the photos themselves–their very existence and reason for being–are evidence of.

If I had to guess, I would say that many people gravitate toward the idea of revelatory violence because its a way of understanding the persistence, ubiquity, and allure of violence without having to concede that the world is a fundamentally brutish place dominated by evil-doers.

I think that’s the genius of O’Connor’s work: the violence in her stories, with the exception of the Misfit, isn’t perpetrated by psychopaths. The violence is carried out by people who consider themselves good Christians. That’s the aspect of O’Connor’s work that really strikes to the heart of this Abu Ghraib scandal, and the much larger scandal involving the CIA. She is so much more than a Southern Catholic writer. She is an astute observer of American life and a the American relationship to the Other. Like Hawthorne (whom she admired), she was concerned with duplicity and how it can lead to gross perversions and abuse.

AR: In light of the above, what do you make of how quickly the violence of Abu Gharib, and all the related questions about American wars, have been swept under the rug so quickly in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo and a myriad of other events?