I love the Septuagint! Well, I love Greek. I find the Septuagint, as a translation and interpretation of the Hebrew Jewish Scriptures fascinating. I love digging into the LXX for help with NT word studies in particular.

I love the Septuagint! Well, I love Greek. I find the Septuagint, as a translation and interpretation of the Hebrew Jewish Scriptures fascinating. I love digging into the LXX for help with NT word studies in particular.

However, I am disappointed that it is not emphasized very much as a resource for pastoral ministry (esp Biblical interpretation), and that many pastors are simply unaware of its legacy, and the influence it has had on the NT writers. Perhaps Ferdinand Hitzig took it a bit too far when he told his students, “Sell all you have and buy a Septuagint!” But he knew something a lot of pastors don’t – there wouldn’t be a New Testament without a Septuagint.

I have spent some time reading articles and essays on the LXX ranging from recent ones to some dating several decades back. Over and over again, scholars have tried to emphasize the importance of the Septuagint for history of Christianity.

Lois Farag wrote this in 2006: “The status of the Septuagint as an inspired text was firmly fixed in the minds of early Christians” (“The Septuagint in the Life of the Early Church,” W&W 2006, p. 393). Another article author, Steven Briel, affirms the same: “Quite simply, the Septuagint was the Bible for the ancient church” (“The Pastor and the Septuagint,” Concordia Theological Journal 51.4 [1987]: 261-274). Briel points back to an article from 1970, where George Howard stated “Paul is…writing the Greek of a man who has the LXX in his blood” (“The Septuagint: A Review of Recent Studes,” RestQ 13 [1970] 154).

Perhaps, with a bit more detail, Melvin Peters’ statement is most persuasive: “It was not a secondary translation to Hebrew but was Scripture. It is quoted, expanded, exegeted, and allegorized in Hellenistic Greek religious literature and thus was the Scripture known to early Christians” (“Why Study the Septuagint?,” BAR 49 [1986] 178).

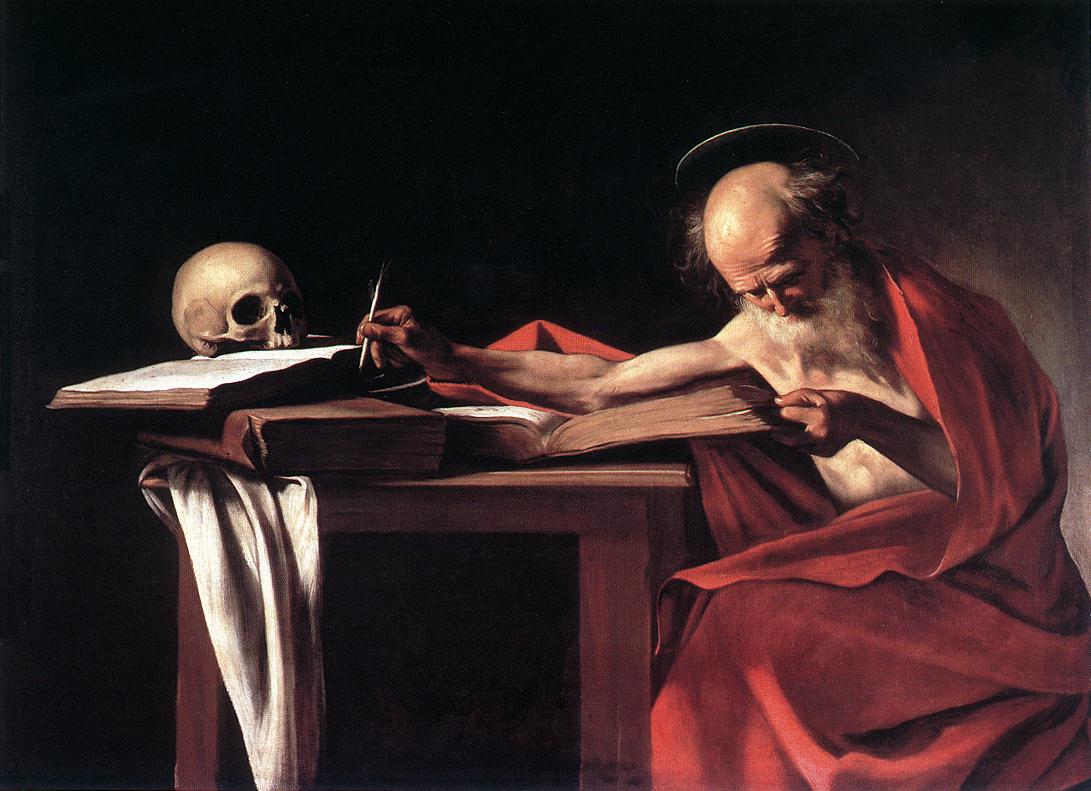

As history tells us, the Septuagint (referred to as LXX, for short) had this status (“inspired”) until the end of the fourth century. What happened then? Put simply, Jerome happened. Basically, Jerome felt that the Latin Biblical translations at his disposal (along with translations in other languages) were convoluted and too often divergent. He desperately wanted to write a new Latin translation. In order to do this properly, he felt compelled to work from the Hebrew texts of the Old Testament (as the earliest sources), and not solely or even primarily from the Greek Septuagint. Two points, though, should be made at this point. First, he had respect for the LXX and considered it inspired (or at least “special”). Secondly, he was not necessarily the voice of an anxious consensus. In many ways, he was alone. In particular, St. Augustine disagreed – quite passionately.

As history tells us, the Septuagint (referred to as LXX, for short) had this status (“inspired”) until the end of the fourth century. What happened then? Put simply, Jerome happened. Basically, Jerome felt that the Latin Biblical translations at his disposal (along with translations in other languages) were convoluted and too often divergent. He desperately wanted to write a new Latin translation. In order to do this properly, he felt compelled to work from the Hebrew texts of the Old Testament (as the earliest sources), and not solely or even primarily from the Greek Septuagint. Two points, though, should be made at this point. First, he had respect for the LXX and considered it inspired (or at least “special”). Secondly, he was not necessarily the voice of an anxious consensus. In many ways, he was alone. In particular, St. Augustine disagreed – quite passionately.

We have the benefit of extant letters from Augustine that express his protest against Jerome’s intentions. Augustine felt very strongly about the Septuagint, even stronger than Jerome. In his work, De Civitate Dei, Augustine wrote, “The Spirit which was in the prophets when they spoke, this very Spirit was in the seventy men when they translated” (18, 43). Interestingly, Augustine apparently believed that the LXX was ordained for the Christian Church because, as a Greek text, it was most suitable for outreach to the Gentile world (see Doctr. Chr. 2.22).

There is an excellent essay by A. Kotze (Stellenbosch) called “Augustine, Jerome, and the Septuagint,” where the conflict between these two theologians is analyzed in detail (see Septuagint and Reception, Brill, 2009). Kotze explains, “In letter 28 of 394 or 395 C.E., Augustine pleads with Jerome not to make a new translation of the OT from the Hebrew and in letter 71 of 403 C.E. he again expresses the wish that Jerome should rather make a new translation of the Septuagint” (245). She adds that there may have been a regional bias at work. The “Western Church Fathers” treated the Septuagint as “normative,” while in the East there was a tendency to prefer the Hebrew text (p. 246).

So, with Jerome’s Vulgate, the Septuagint began to fade. However, the “acceptance” of the Vulgate did not happen overnight. It took a couple of centuries for it to gain traction (the Venerable Bede used the Vulgate in his commentaries). However, after Jerome, it appears that the Septuagint started to lose its prize place as the primarily “inspired” translation of the Christian Church.

What about the Apocrypha? Did it fall out of use after Jerome? Good question. That will be the subject of the next post in this series.