Recently I finished reading Joe Hellerman’s Embracing Shared Ministry: Power and Status in the Early Church and Why It Matters Today (Kregel, 2013). The book of nine chapters is comprised of 3 sections: Power and Authority in the Roman World (chs. 1-3), Power and Authority in the Early Church (chs. 4-6), and Power and Authority in the Church Today (chs. 7-9).

Recently I finished reading Joe Hellerman’s Embracing Shared Ministry: Power and Status in the Early Church and Why It Matters Today (Kregel, 2013). The book of nine chapters is comprised of 3 sections: Power and Authority in the Roman World (chs. 1-3), Power and Authority in the Early Church (chs. 4-6), and Power and Authority in the Church Today (chs. 7-9).

In my view, this book synthesizes and brings together in one place a number of interests Hellerman has  regarding Biblical texts, the nature of leadership in the early church, and the proper operation and leadership of ministry in the church today. Three ideas are reinforced in this book: (1) the Christological inversion of the Roman honor-contest, (2) the purposeful choice of Paul to use kinship language for fellow-believers to undercut honor-competition, and (3) the importance of a vision of “shared leadership” in the church today (where there is no solitary figure at “the top,” but, rather, a communion of leaders who share authority as well as the pulpit).

regarding Biblical texts, the nature of leadership in the early church, and the proper operation and leadership of ministry in the church today. Three ideas are reinforced in this book: (1) the Christological inversion of the Roman honor-contest, (2) the purposeful choice of Paul to use kinship language for fellow-believers to undercut honor-competition, and (3) the importance of a vision of “shared leadership” in the church today (where there is no solitary figure at “the top,” but, rather, a communion of leaders who share authority as well as the pulpit).

Let me say: the first two sections of the book almost speak for themselves and are well worth the cost of the whole thing. Every pastor who cares to understand Paul and his world should read the first 200 pp. of this book. Put inversely, whoever has not learned the lessons in this book is missing out on the heart of Paul’s theology of cruciform leadership.

I am going to take some time now to walk you through the earlier parts of the book, the chapters that drew me in the most.

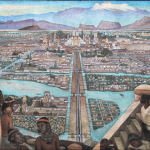

In the introduction, Hellerman notes that this book focuses on cruciformity: “The Christian life, at its essence, is a cruciform life. It is a life that is shaped like–and shaped by–the cross of Jesus Christ” (p. 15). In order to see how this works in the NT, we must understand Paul’s Roman world (hence, ch. 1). A main focus of this book is on Philippians, and Hellerman underscores the fact that Philippi was a Roman colony; thus, “the town was Roman in ways that other Pauline church-planting locales were not–especially the colony’s social values” (24). In the Roman world, especially identifiable in a place like Philippi, we see that everything revolved around honor. Hellerman writes,

Christianity was born in a world where honor was everything, and where persons in positions of power…were quick to use their authority publicly to humiliate or abuse their inferiors, if by doing so they thought they could somehow enhance their own status of that of their extended families (p. 30).

The people of Philippi had been socialized for generations to embrace the status-conscious, honor-oriented values of their cultural world. Paul encouraged the Philippians to adopt, instead, the radically alternative servant-oriented approach to human relations exemplified in the attitude and behavior of Jesus of Nazareth (p. 26).

Hellerman explains how the wider population could be categorized as either “elite” or “non-elite” – and the “elite” consisted of only about 2% of the population (some 50 million people). Philippi itself had 500 men of elite (decurion) status in the first century (of c. 20,000 people). In a context where status was the only lasting currency, the Christian emphasis on humility was ridiculous.

Jesus’ challenge to James and John would have struck Mark’s honor-seeking, self-serving Roman readers as utter nonsense–indeed, if put into practice, social suicide. (p. 42).

In the next chapter (2), Hellerman expounds upon the “honors race” in the Roman world. Great charts illustrate the levels of upward mobility. And even if one were not an elite, there were more modest versions of the race in voluntary associations (for example). Even Paul recounts his own Jewish version of the cursus honorum in Phil 3:5-6.

In chapter 4, Hellerman begins to look at how Paul (and other NT writers) work against the honors race.

Paul’s goal was to create a very different kind of community among the followers of Jesus in first-century Philippi. The Philippian church was to be a community that discouraged competition for status and privilege, a place where the honor game was off-limits, in summary, a community in which persons with power and authority used their social capital not to further their own personal or familial agendas but, rather, to serve their brothers and sisters in Christ (106).

How does Paul paint a picture of the divine vision of community? — by narrating the story of the humiliation of Christ (ch. 5) in Philippians 2:6-11. As Hellerman writes, “Such behavior [of self-lowering] would have struck Roman residents of Philippi as abject folly” (140). Another apostolic strategy is employed – the use of kinship (esp siblingship) language – the honor game was “off-limits” for siblings. By calling each other “brother” and “sister,” Christians saw their fellow believers as family members, not sources of honor.

The remainder of the book involves case studies of how places where there was strict top-down authority (with a solitary pastor on top) led to manipulation, unwarranted firing, and mistreatment of lower-rung church works. Hellerman makes a strong case for shared leadership. He offers both theoretical and practical advice.

Evaluation: This is an outstanding book, distilling many years of his research, teaching, and pastoral ministry from a Biblical perspective. Seminary students would do well to heed this advice and embrace the cruciform vision of leadership that he proposes.

I only have a few concerns with this otherwise impeccable study, mostly in the latter chapters. Firstly, while I think much can be gained from his reading of the cruciform nature of Christian leadership, and that shared ministry is important, Hellerman could have explored a number of (other) ways to “apply” the theology of Phil 2:5-11 to leadership challenges today (shared leadership being only one solution). In the several interesting case studies, while Hellerman identified shared leadership as the go-to solution, I think things like “transparency” in leadership process was equally failing (which is not necessarily impossible with a solitary leader) . Also, one could obviously conceive of shared leadership being helpful, but if the communion of leaders become a magisterium, what is to stop them from collectively abusing their power? My point here, perhaps, is that I would have liked Hellerman to have articulated a personal virtue of cruciform leadership (alongside or in addition to a church governance solution).

Finally, while Hellerman’s case studies were appropriate to his argument, only one (out of several) focused on a women leader. Now Hellerman himself ministers in a church with exclusively male pastors, and the academic context in which he teaches largely focuses on male-only pastoral ministry (I presume), so I really can’t blame him for using examples from what he knows and where he has experience. But that means his book has limited reach. If I assign this book for class, I run the risk of giving the 40% female student body a book full of examples of men (save one). Again, I know the audience Hellerman is reaching, and I respect that this is his world. He is frank about that and I am mentioning it because this is the only area where I hesitate to use this book for class.

I am so glad, overall, Hellerman went ahead and wrote a more accessible (and affordable) version of his earlier work Reconstructing Honor in Roman Philippi. I am grateful to have this book in my library and I expect to appeal to it often. I have long said that his reading of Philippians is compelling and deserves wider attention and appreciation. This book is a handy resource for learning from Hellerman’s outstanding scholarship.