A New Blog Series: Translating Philippians

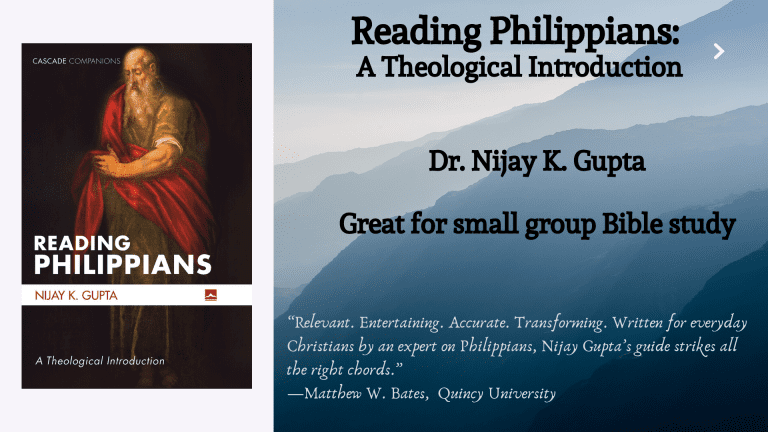

This is a new series reflecting on Bible translation by looking at the Greek text of Philippians. In my book Reading Philippians, I offer my own fresh translation of this letter. I tried to provide a readable, modern English translation, which means I made some untraditional choices. Follow along as I talk through some of these decisions. We begin with Philippians chapter one.

“Paul and Timothy, Christ Jesus’s Slaves (douloi)” (1:1)

Here I chose to render douloi, sometimes translated “servants,” as “slaves.” The word doulos was commonly used in the ancient world, and in Paul, in reference to the legal status of slavery. Paul uses it metaphorically here, but in any case it would have been an evocative word for Paul’s readers. Later in Philippians he uses this term again in reference to Christ who became like a doulos, giving up his glorious status and power to become human and even die on a cross (Phil 2:7). Paul had a clear intention in this letter to subvert the readers’ notions of status and power, and I think he begins this conversion of their imagination from the start.

“Filled Up with the Fruit of Justice and Integrity (dikaiosynes) (1:11)

Almost without exception, translations will have “righteousness” here. To the modern American ear, “righteousness” is an old-timey religious term. But Paul was using a Greek word (dikaiosyne) commonly used in his time for rightness. I had troubling finding a suitable English term for dikaiosyne. Some scholars advocate for “justice,” which clarifies the social dimension of dikaiosyne. But I felt that was not enough. This word, when used to describe a person, often refers to a personal value, not just that they are justice-seeking, but that they are a good, upstanding person in general. I decided the English word “integrity” fit that concept nicely. So, I felt that dikaiosyne is best represented by a combo of “justice and integrity.” It is a bit awkward, but I think good Bible study will break away from overly familiar religious language and shake things up sometimes to get us thinking about the “real” meanings of these words.

“My Dear Brothers and Sisters” (1:12)

Paul sprinkles throughout this letter the term of endearment adelphoi for the Philippians. This word means “brother,” but metaphorically applies to everyone in the church, hence it is often translated “brothers and sisters.” I decided to add the word “dear” to communicate the warmth and intimacy involved in Paul’s usage. It was not normal for friends to call each other “brother/sister” when they weren’t biologically related. And it was especially uncommon for someone to call another person “brother/sister” who was outside their ethnic group. But Paul was doing precisely this for theologically reasons in this letter (and his other letters, of course). This was more than a friendly greeting—hey bro! It was a deconstruction of the sharp dividing lines in society that established a hierarchy of privileged ethnic groups (like Romans). It was correspondingly a testimony to the one family or household of faith in Jesus Christ.