I am excited to share with you this interview I conducted with Dr. Lisa M. Bowens (Princeton Theological Seminary). Her new book is really well written and deeply insightful.

Lisa M. Bowens, Princeton Theological Seminary

What inspired you to write this book? And why Paul as a figure of focus?

A couple of things happened over the course of time. First, I was working on my dissertation on 2 Corinthians 12, Paul’s ascent, which became my first book, An Apostle in Battle: Paul and Spiritual Warfare in 2 Corinthians 12:1-10, and I wanted to include a chapter on African American interpretation of that passage in my dissertation. My doktorvater (doctoral supervisor) suggested that chapter should be its own separate work apart from the dissertation.

About the same time this conversation was taking place, I kept attending different conferences in which the story of Howard Thurman’s grandmother, Nancy Ambrose, repeatedly came up and the assumption seemed to be that this story was the primary way African Americans approached Paul and his letters (By the way I begin the book with this important and provocative story). Both of these events, my advisor’s suggestion and these conference meetings, converged for me and I began to wonder if Nancy Ambrose’s story represented the way most African Americans felt about Paul. So, I decided to do an investigation and just see what I could find. I wasn’t sure what the outcome would be but I was curious.

Thus, I decided not to just focus on African American interpretations of 2 Corinthians 12 but African Americans’ use of Paul more broadly. As it turns out, my research shows that Paul was a central figure for African Americans throughout history as indicated by the amount of times they reference or cite him and his letters. In addition, I found that a majority of these interpreters view Paul in a positive light and use him to argue for justice, freedom and equality. This book, then, is a result of this investigative journey. On a personal note, I’ve been interested in the apostle Paul and his letters since I was little. He has fascinated me for quite some time.

Research is always full of surprises. What surprised you in your research on this subject? What did you encounter that was unexpected?

When I decided to expand my research and focus on African American interpretations of Paul more broadly, I naively assumed that I could cover most of the material from the 1700s to the present and that I could cover most, if not all, African American interpreters who utilized Paul in their work. However, it became clear to me the more I did my research that such an endeavor was impossible—there are too many interpreters and too many sources. That was a nice surprise because it shows that the relationship between African Americans and Paul is strong and that this relationship spans centuries and genres. It also points to the complex nature of that relationship.

Consequently, I had to shorten the time frame for the book, 1700s to mid-twentieth century, and I had to limit the amount of sources and interpreters I focused on as well. I was also surprised that I did not find many African Americans who disliked Paul or rejected his letters. I discuss two such interpreters in my book, but I thought there would be more who followed this trajectory, especially considering how proponents of slavery used Paul to justify slavery.

Do you have any favorite African-American interpreters or favorite specific African-American texts that you encountered in this research?

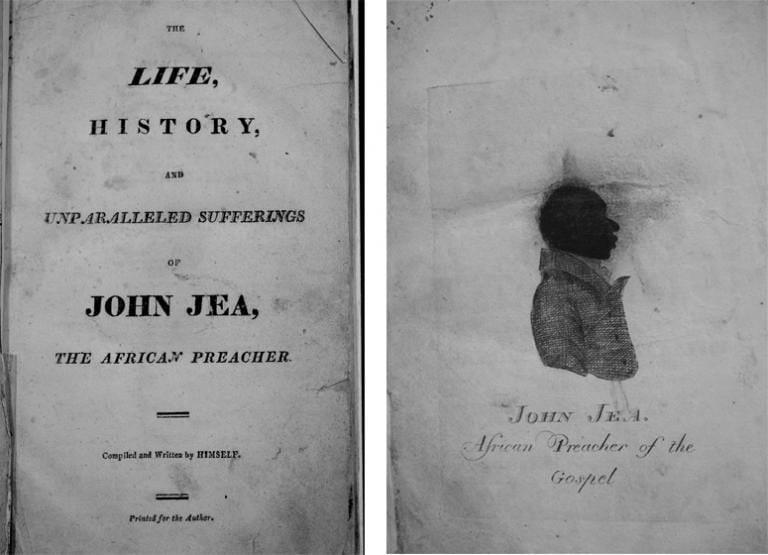

Hmmm….This is a hard question because as I researched and studied each of these interpreters I found myself drawn into their writings and into their worlds, so to speak. I have a deep appreciation for all of them, for they are all profound and insightful. So, it is difficult to choose one. I think one interpreter I can lift up is John Jea, an enslaved African, born in the 18th century and whose autobiography is powerful on so many levels. In his narrative, he tells of how God taught him to read. It’s an amazing story of faith and liberation. Likewise, many of the African American women I talk about in the book had extraordinary divine encounters with God. For instance, Zilpha Elaw, a 19th century preacher, says of one of her encounters that she cannot tell whether she was in the body or out of the body. The remarkable descriptions of these events by these women bear witness to God’s power.

Hmmm….This is a hard question because as I researched and studied each of these interpreters I found myself drawn into their writings and into their worlds, so to speak. I have a deep appreciation for all of them, for they are all profound and insightful. So, it is difficult to choose one. I think one interpreter I can lift up is John Jea, an enslaved African, born in the 18th century and whose autobiography is powerful on so many levels. In his narrative, he tells of how God taught him to read. It’s an amazing story of faith and liberation. Likewise, many of the African American women I talk about in the book had extraordinary divine encounters with God. For instance, Zilpha Elaw, a 19th century preacher, says of one of her encounters that she cannot tell whether she was in the body or out of the body. The remarkable descriptions of these events by these women bear witness to God’s power.

When I was reading your wonderful book, I wasn’t prepared for how powerfully emotional it is to read such harrowing accounts of racism, discrimination, abuse, etc. Did that affect you? How did you handle it?

Yes, reading these writings were difficult at moments. At various points I cried, I experienced disappointment, and anger. For me these works compelled a range of emotions. There were times when I had to take some time away and other times I decompressed by talking to my family about what I was reading and I discussed with them the different interpreters I happened to be studying at the moment. At the same time, I also experienced great inspiration and hope from these African Americans and their writings. While these texts challenged me, they filled me with hope. I was encouraged by these interpreters’ tenacity, their unshakeable faith, and their relentless belief in the power of God and the power of the gospel, if adhered to faithfully, to transform individuals, communities, and the nation. Their stories and their writings have definitely left an imprint upon me and I hope that readers also feel connected to them when they read the book.

My fear with a book as important as yours is that it will be treated as a “niche” topic, only of interest to those interested in African-American interpretation or reception studies. But I hope a much broader audience reads this book—I assume you do too. How do you think a study like this benefits how we study the Bible, and in particular how we study Paul, today?

I think these interpreters leave us a legacy of how scripture is God’s word and is a word on target for the contexts in which we find ourselves. They offer us insight into ways forward in the current climate in which we are now living in which issues of race, racism, the church, and Christianity are again at the forefront. Can Paul speak to these issues? Can one view Paul as a figure of resistance and protest? When we read these writings, we see that these hermeneuts (interpreters) answer affirmatively to such queries. Also, what does it mean to interpret scripture well and faithfully? Again, I think these authors show us ways to do that. I would also add that the research included in the book involves a three-layered nexus of historical, theological, and biblical work so I hope that those interested in history and theology will find it compelling as well. In addition, the book discusses different genres in which African American interpreters utilized Paul to protest racism, oppression, and injustice—ranging from enslaved petitions to essays to sermons to conversion narratives. They show us that the Bible is relevant and is a source against racism, injustice, and oppression, all issues which believers need to address in living out the gospel. And finally, I hope that the interpreters featured in the monograph become important conversation partners in Pauline studies and that their voices become a part of the discussions around apocalyptic thought in Paul, protest and resistance hermeneutics, hermeneutics of trust, and the art of biblical interpretation.

Get the Book