My friend David Moffitt (University of St. Andrews) talks about some of the key ideas in his new book: Rethinking the Atonement (Baker Academic, 2022)

The Atonement—Jesus’s Work Goes On (And On!)

David M. Moffitt

Debates about the atonement have raged in theological circles for many years now, with wagons circled around favored theories such as penal substitution, moral example, ransom theory, Christus Victor, and so on. While advocates of various camps fiercely contend for elements of their preferred view, one point of common ground rarely questioned is the centrality of Jesus’s death for the atonement. Jesus’s once-for-all sacrifice of himself to God on the altar of the cross is often self-evidently assumed to be the center of the atonement. The debates and disagreements typically revolve around how to interpret and explain the salvific effects of this singular sacrifice.

Debates about the atonement have raged in theological circles for many years now, with wagons circled around favored theories such as penal substitution, moral example, ransom theory, Christus Victor, and so on. While advocates of various camps fiercely contend for elements of their preferred view, one point of common ground rarely questioned is the centrality of Jesus’s death for the atonement. Jesus’s once-for-all sacrifice of himself to God on the altar of the cross is often self-evidently assumed to be the center of the atonement. The debates and disagreements typically revolve around how to interpret and explain the salvific effects of this singular sacrifice.

Sometimes theologians offer metaphors to describe the cross and the atonement, such as a gemstone with multiple facets that offer different perspectives or as a house with windows that look out in multiple directions on different vistas. These metaphors attempt to grapple with the reality of the New Testament’s witness to a diverse number of problems that keep God and humanity apart, problems that are solved by the death of Jesus and the atonement that event effects. Enslavement, sin, impurity, to name only a few of these problems, are all resolved by Jesus who redeems the enslaved, forgives the sinners, and purifies the impure.

But does Jesus solve all the problems that separate God and humanity at the same time and in the same way? Was all the atoning work of Christ done when he died on the cross? Unlike cross-centered theories of atonement, the author of Hebrews and some other New Testament writers assume a narrative of the Son’s incarnation that reveals that the atonement involves much more than just the cross.

The essays in my new book Rethinking the Atonement: New Perspectives on Jesus’s Death, Resurrection, and Ascension aim to expand the scope of theological reflection on the atonement by questioning this modern reduction of Jesus’s sacrifice and the atonement to the event of the crucifixion. These essays do not argue for a particular theory of the atonement. Most of them seek in one way or another to show that careful attention to the New Testament’s reflection on the saving work of Jesus, especially in the Epistle to the Hebrews, should draw our attention to far more in the story of the eternal Son’s incarnation than just the event of his death on a cross. Jesus’s death is essential for atonement, but so also are his resurrection, ascension, ongoing intercession, and hoped-for return. Each of these aspects of the narrative of the incarnation of the eternal Son contribute in distinct ways to the salvation Jesus makes possible for those who come to God through him.

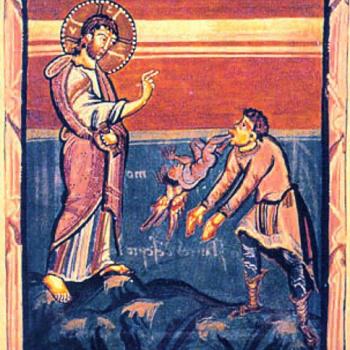

Some will object that expanding the scope of the atonement in this way diminishes the salvific significance of the cross, but such a response illustrates one of the problems the essays in this book attempt to redress: a myopic and reductive focus on the event of Jesus’s death. For a great many New Testament scholars and theologians today, aspects of the gospel proclaimed in the New Testament that highlight Jesus’s resurrection and ascension are essentially reducible to early Christian reflection on the profound significance and impact of Jesus’s death on his earliest followers. But what if early Christians really believed that Jesus rose bodily and ascended as a human being through the heavens into a heavenly tabernacle to offer himself to his Father and now serve there as his people’s great high priest? Such an account of the Son’s ongoing incarnate work would require a rethink about how Jesus atones for his people.

Rather than denying the importance of the crucifixion, the essays in this book locate this event within the bigger contexts of the incarnation and the relational dynamics of the Old and, in analogous ways, the New Covenant. Hebrews in particular attests an understanding of Jesus’s atoning work that places as much, if not more, emphasis on the ongoing high-priestly work of the incarnate Son before the Father in the heavenly holy of holies. This broader approach highlights afresh the importance of Jesus’s ascension to the Father and his perpetual work of intercession in the heavenly tabernacle. This is one essential way in which he now atones for his brothers and sisters. Moreover, as some of these essays demonstrate, the recognition that Jesus’s ongoing intercession is as essential to accomplishing salvation as was his death (and resurrection, and ascension) is as much a task of recovering elements of past theological reflection as it is of offering fresh, biblical interpretation.

This larger scope on the full sweep of the Son’s incarnation not only recovers the significance of Jesus’s ongoing intercession for his siblings, it also exposes some common misconceptions about sacrifice that often go unnoticed in modern conceptions of the practice. Consider just one way in which we today misconstrue sacrifice. Many of us take as fact that in Jerusalem the central act of sacrifice occurred when a priest put an animal on the temple’s main altar and killed it. Everything revolved around this central event. The notion is reinforced by online videos, paintings, and pictures that depict animals bound and bleeding on an altar. Yet this common conception is factually wrong. No animals were slaughtered on any of the altars at the temple in Jerusalem. The focal point of sacrifice was not the slaughter of the animal, but its conveyance by a priest as a gift into God’s presence in his temple.

And this emphasis on moving into God’s presence is precisely the direction and focus of the Son’s travel in Hebrews, which presses us to see the ascended Jesus now working for us before the Father in the heavenly tabernacle. Observations like this not only help us read texts like Leviticus more carefully, they also indicate the extent to which early Christians were far better versed in the logics and practices of Jewish sacrifice than many of us are today. Hebrews is often thought to be thoroughly dismissive of Jewish sacrifice. Yet, a recovery of the importance of Jesus’s resurrection and ascension to the heavenly altar as high priest suggests instead that this early Christian writer finds numerous analogies and patterns in Jewish scriptures and practices such as sacrifice that align with and even inform how he constructively reflects on who Jesus is and what Jesus does to save his people.

Rethinking the Atonement does not intend to endorse (or deny) any one of the many theories of atonement on offer today. These essays seek instead to expand the category of atonement in ways that move beyond one of the common assumptions shared by many of these theories—the view that Jesus’s death is the sum-total of his sacrifice and the sum-total of his atoning work. Such an account diminishes the incarnation. We do better to think more broadly about who Jesus was, is, and is to come, and what he did, does, and will do to save his people from their sins.