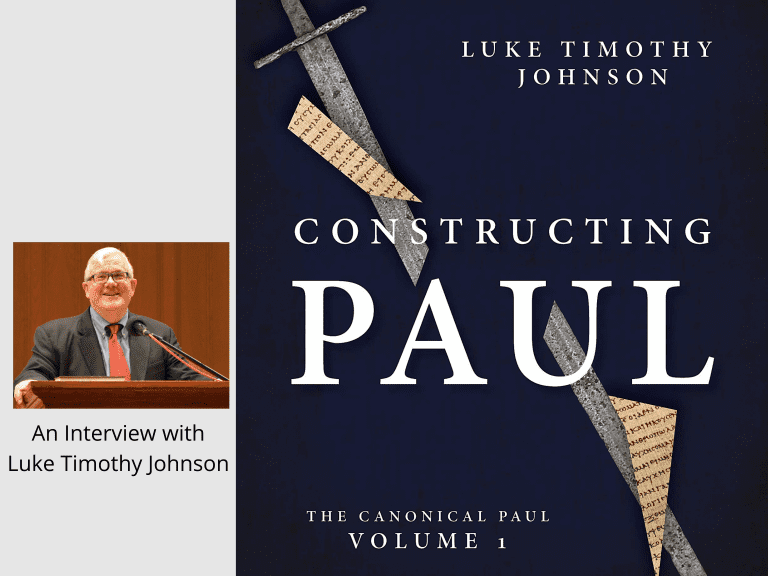

This is PART 2 of my interview with Luke Timothy Johnson, Robert W. Woodruff Professor Emeritus of New Testament and Christian Origins at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. In this interview (part 2), Johnson talks more about his book Constructing Paul and some other projects as well.

NKG: You offer one key case study for your approach to Paul in this volume: Philemon. (You cover Paul’s other letters in your next volume) Why did you decide to front load Philemon? How does this short letter demonstrate well the approach you take to studying Paul.

LTJ: Philemon is an inviting entry into Paul’s letters (as others before me have seen) first of all because it presents a “Paul” who escapes both the “old” and “new perspectives,” who writes in response to a pressing practical issue (the return of the slave Onesimus to his legal owner), and in the process shows himself charming, witty, and completely at home in the world of Greco-Roman diplomacy, playfully — yet seriously — tweaking the system of patronage and the culture of honor and shame in original and effective ways.

Yet Philemon also presses the question that New Testament scholarship seldom faces head-on: why should a personal note to an otherwise obscure personage be included — without debate and from the beginning — as part of the New Testament canon? Perhaps, I suggest, it is because Philemon was part of a three or four letter packet of letters delivered by Paul’s delegate Tychichus, a packet that included letters to the local churches at Colossae and Laodicea (not extant), with the letter to the Colossians being delivered and read aloud to the assembly at the same time as he returns Onesimus. Tychichus would also at each stop read the circular letter we know as Ephesians. In this reading, Philemon is a letter of personal commendation, Colossians a letter to the local church, and Ephesians a circular letter to the circle of Pauline communities in Asia and Phrygia.

I draw the analogy to the three Johannine letters delivered as a packet to the Elder: note of commendation for the delegate (3 John), cover missive tot the local church (2 John), and a sermon to be read aloud in the assembly (1 John).

The payoff of this construal is that it explains the intricate network of names among Colossians, Ephesians, and Philemon; it identifies the rhetorical function of each letter; it explains why a private note should find its way into the canon; and, best of all, it enriches the reading of all three canonical letters when they are read together (see especially my discussion of the passages dealing with slaves and masters in Colossians and Ephesians).

NKG: If you could have students of Paul read one other academic book about Paul (other than Constructing Paul), what would it be and why?

LTJ: Three continental scholars of the last generation especially deserve attention. The first is the Belgian scholar, Lucien Cerfaux, whose essays (many of them available in collected form) are marked by a combination of wide-ranging knowledge of ancient sources and a close exegesis of specific passages. The second is Johannes Munck, whose Paul and the Salvation of Mankind illustrates how a truly independent mind can reach conclusions that are consistently both sane and startling. The third is Nils Dahl, whose Studies in Paul remains seminal. I note that none of these scholars began or ended with a “big idea” or overarching theory. They were each servants of the text, following where it led them. They all wrote simply and to the point. When all the major theory entries fade, they continue to instruct and illuminate the writings of Paul.

NKG: If you could use your book Constructing Paul to change one thing about how scholars look at Paul, what would that be?

LTJ: My hope is to encourage scholars who profess to work in service of the church to take seriously the canonical status of all 13 Pauline letters, to open their inquiry to that larger field of evidence, and to discover, through engagement with all these letters on an equal footing, that they offer exciting new possibilities of insight. When viewed from the perspective of the canonical Paul, for example, both so-called “old” and “new” perspectives are revealed as dealing with a very small part of the Pauline evidence, and neither can support to claim to “explain” Paul when they ignore the largest part of the Pauline collection. The point, I hope we call come to realize, is not to provide a singular vision of what Paul thought, but rather to explore the many questions that arise from considering all the data, questions that are pertinent above all to the life of faith and the living out of that faith in every age.

NKG: What are some big ideas that you will be aiming to communicate in your future second volume?

LTJ: Readers of my second volume, Interpreting Paul, which is in press and should be out in March 2021 will not find a singular argument concerning the meaning of “Paul” or a “Pauline Theology.” They will find a set of some 25 essays that deconstruct such artificial representations through close attention to the contours of each canonical compositions — learning the questions they pose and how reading them in conversation with each other yields a more fragmentary but also more fascinating sort of understanding.

The essays, to be sure, deal with not a few “big” notions found in the canonical letters: the faith of Jesus, the ontological and social entailments of resurrection, truth and reconciliation, the pedagogy of grace, the transformation of the mind, the meaning of fellowship in suffering, how mystery and myth and metaphor express reality, the social character of salvation, and others. These questions arise from the text as we stumble over its meaning, and they arise from all the canonical letters with equal force and pertinence.

I have not intended to provide — and surely have failed to provide — an “Interpretation” of Paul that synthesizes all the data according to some schema. I think such an effort foolish on the face of it, and regard it as obstructive to my real goal, which is to invite the reader to join me in “Interpreting Paul” in an on-going and constantly changing conversation, as the Spirit and our own sweat enable us to learn new and deeper insights into the apostle of Jesus Christ.

NKG: As you settle into retirement, we still hope you continue writing. What other writing project do you have planned?

LTJ: This will probably be my last major scholarly book. My age and physical infirmities make the sort of athleticism required to do first-rate scholarly work less possible. I am in conversation with a publisher about the publication of a selection of my “public theology” essays, some two hundred of which I have scattered in various ecclesially inclined magazines over the past forty years. We’ll see if that happens.

If I do write another book, it will deal with the life of the scholar, as it was in the past, and how it is changing. My tentative title is “The Mind in Another Place: What it Means to be a Scholar.” But I need to convince even myself that this is worth doing!