***

In a 16 May 1767 letter to Étienne Noël Damilaville, the French writer Voltaire (1694-1778) said “Je n’ai jamais fait qu’une seule prière à Dieu, une très courte «Ô seigneur, rendez mes ennemis ridicules». Et Dieu l’a accordé.” (“I have never made but one prayer to God, a very short one: ‘O Lord, make my enemies ridiculous.’ And God granted it.”)

Some of the things that I’ve read online over the past few days have powerfully reminded me of Voltaire’s witticism.

***

On the road yesterday from Minneapolis, just a few miles before our destination in Alexandria, Minnesota, we saw a billboard for Jacobs Lefse Bakeri & Gifts. I was thrilled. I grew up loving Norwegian potato lefse, made according to my grandmother’s recipe. I didn’t get it very often. Every few years at Christmas. And — it’s fairly labor-intensive — I still don’t get it often. Every few years, perhaps. And, honestly, the flour lefse that seems more common in Norway itself and that is sold at the Norway Pavilion at Epcot in Orlando, while it’s pretty good, just isn’t the same.

It was too late yesterday, but this morning we headed back a few miles from Alexandria to the bustling lakeside metropolis of Osakis, Minnesota (population approximately 1740), and found Jacobs Lefse Bakeri & Gifts. And I’m delighted to report not only that they make potato lefse — which is to say, the one and only true lefse — but that it’s some of the best that I’ve ever had. As is their Norwegian flatbread (flatbrød) and their almond cake. These things have helped to put me in a rather Scandinavian mood.

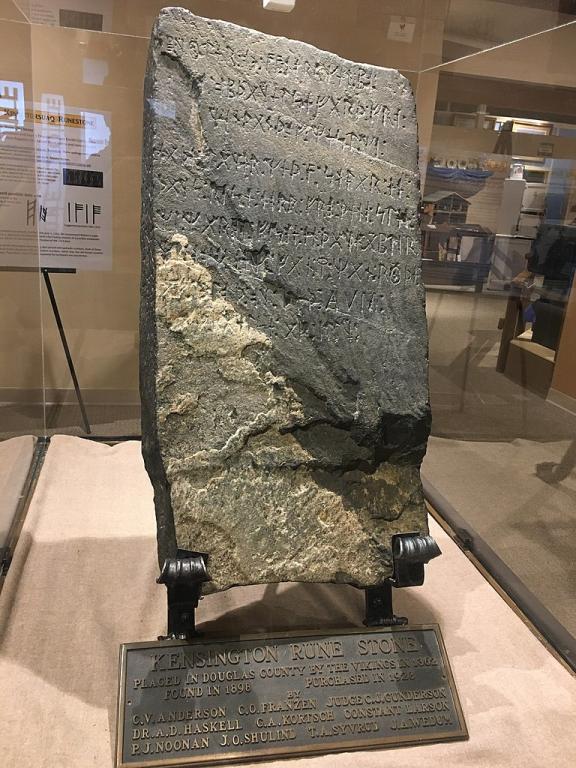

Which is appropriate, because we next drove straight back to Alexandria to visit its small but surprisingly interesting Runestone Museum, home of the famous and controversial Kensington Runestone.

And, you may be asking, just what might the Kensington Runestone be?

It’s a 202-pound (92 kg) slab of greywacke stone — 30 × 16 × 6 inches (76 × 41 × 15 cm) — that was allegedly discovered by the Swedish immigrant farmer Olof Öhman in 1898. He and his sons, he said, were clearing a field near the settlement of Kensington, not terribly far from Alexandria, when they found the stone entangled in the roots of a somewhat stunted poplar or aspen tree. His son Edward noticed markings on the stone that, Olof Öhman later recalled, they initially took to be “Indian markings.” It turns out, though, that the “markings,” which appear on one side of the slab and on one of its edges, are medieval Norse runes. The inscription, which dates itself to the year 1362, claims to be a record left behind by a Scandinavian exploration party in the fourteenth century:

Eight Goths and twenty-two Norwegians on an exploration journey [or acquisition expedition] from Vinland to the west. We had camp by two skerries one day’s journey north from this stone. We were [out] to fish one day. After we came home [we] found ten men red of blood and dead. AVM (Ave Virgo Maria) save [us] from evil.

[We] have ten men by the sea to look after our ships, fourteen days’ travel from this island. [In the] year 1362.

The majority viewpoint, since its discovery, has been that the Kensington Runestone is a modern forgery. But there are seemingly solid scholars who continue to argue for its authenticity. And the Öhman family has always denied forging the inscriptions on the stone: As Olof Öhman’s son Edward declared, late in his life, “Them boys was here alright!”

What difference would a genuine Kensington Runestone make ? If authentic, the Runestone suggests the presence of Scandinavians far deeper in mainland North America, and considerably later, than most have thought. Which has led the good and perhaps somewhat cheeky folks in Alexandria to call their town “The Birthplace of America.”

I have no real investment either way, of course. Nothing that I really care about depends upon the genuineness of the Kensington Runestone. But it’s an interesting question, and I was delighted to actually see the Stone after hearing about it for many years.

Actually, let me walk back a bit what I just said above: I have no real investment in the authenticity of the Kensington Runestone. That’s true. Nothing direct. But I like it very much when history surprises us, when things turn out to have been more complex and more interwoven than we had expected. I loved learning, for example, that Chinese paper-making techniques were conveyed to the Arabs by Chinese prisoners of war after the Battle of the Talas River in Central Asia in AD 751 — although it now appears that the manufacture of paper had already entered Central Asia a century or two before that battle. And the thought that there may have been Buddhist missionaries at the court of the Ptolemies in Alexandria pleases me very much. I like it when two “worlds” previously thought to have been quite separate from each other turn out not to have been, when our neat compartments are broken down. I would have been delighted if the Loch Ness Monster had turned out to be real, and a plesiosaur. As a kid, I was happy to read how, although the fish known as coelacanths were thought to have become extinct in the Late Cretaceous Period, around 66 million years ago, living coelacanths were discovered off the coast of South Africa in 1938. I guess, in some sense, that I enjoy the disruption of paradigms.

But now we’re here in the general area where my father was born and where he was raised by his Danish-born father and his Norwegian-born mother. This is the reason for this portion of this trip. I haven’t been here since I was a teenager, and I’ve wanted to make the pilgrimage for a very long time. I don’t remember much, if anything, from that last trip, and I don’t know what or how much I’ll learn from this one. Things have changed a great deal since my father left for California during the depression. Everybody, including my grandparents, eventually came to southern California, and I’m aware of no relatives who still live here. My grandfathers both died before I was born; my grandmothers both died when I was five, and I scarcely remember them. My parents are both gone, as is my only sibling, as are all of my uncles and aunts. But I’ll at least be walking the ground of the place that formed my father and my aunts and my uncles. And that, to me, is something very worth doing. It is, I suppose, a quest for roots. And an act of homage.

Posted from Devils Lake, North Dakota