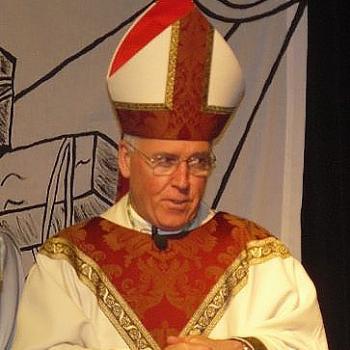

The Newark prelate gave what appears to be his first interview on the case to Joan Frawley Desmond of the National Catholic Register late last week:

Critics of your decision to allow a restricted role for Father Fugee as co-director of the Newark Archdiocese’s Office of Clergy Formation charge that you violated the U.S. bishops’ Charter for the Protection of Children’s “zero tolerance” policy for all priests with credible accusations of clergy abuse. According to the public record, Father Fugee admitted to groping a young man, entered a rehabilitation program and underwent counseling for sex offenders. Would you describe the decision-making process that allowed him to return to ministry?

Many of the facts regarding Father Fugee’s case have not been fully reported or have not been presented in a balanced way.

We worked with the prosecutor’s office and our lay review board, and we were professional throughout. The memorandum of understanding worked out with the prosecutor’s office said he could function as a priest, but not with minors in an unsupervised capacity.

The assignments I gave him were intended to increase supervision. He was in the chancery eight hours a day, and he was working with another priest to identify places where priests could participate in retreats. In that role, he had no contact with children.

Would you address the charges against Father Fugee and how his case was decided?

There were two charges against Father Fugee. He was found innocent of one involving endangerment and guilty of the other involving contact.

However, a three-judge appellate court threw out the guilty verdict. The panel of judges determined that the judge’s instructions to the jury lacked guidance on how to deal with whether Father Fugee was acting in a supervisory way with the young man, such as a coach or a teacher. The court said the lack of guidance resulted in the jury’s inability to consider critical elements of the matter.

In addition, a juror reported to the judge that she felt the priest was innocent and that jurors seeking a conviction had apparently misled other jurors about what the judge and attorneys said. The judge did not look into the matter.

Whatever the details of the case and its outcome, Father Fugee acknowledged in his March 19, 2001, statement to the police that he had “grabbed” the privates of the 14-year-old boy while he and the boy were wrestling, fully clothed.

The statement out there is part of a larger period of questioning over some three hours that was not taken down. During that larger period, he denied any wrongdoing several times. When the case went to court, Father Fugee testified that he said what he did in the written statement by mistake at the end of the three hours because he was tired.

The average person is looking for a black-and-white answer, but there are cases where there are more grays than black and white. That is what the court and the review board were dealing with.

A psychiatrist’s evaluation undertaken at the direction of the court after Father Fugee won the appeal concluded that he was not a danger. After the evaluation, the Bergen Country prosecutor said he could go back to ministry.

Our lay review board looked into the allegation as if they were cops looking into the matter. They conducted a series of confidential interviews, read through the documents and had a lot of discussion.

The review board did not give Father Fugee a clean bill of health: He engaged in activity that was ill advised but did not rise to the level of sexual abuse. They said the limitations stated in the memorandum were appropriate safeguards. There would be no unsupervised ministry with minors and youth. He could say Mass when young people were present. He could do baptisms and funerals.

The case went to the review board in late 2006 and was not completed until 2009. We incorporated the terms of the memorandum into a precept. So the directive did not just come from civil authorities; it was also approved under canon law for the diocese.

If he were to go outside the diocese to minister to young people, he still needed permission to do that, and he knew we would have told him, “No.”

There’s much more. Read the rest.