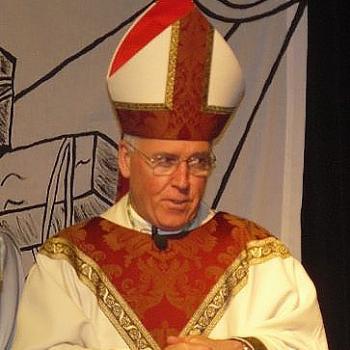

From the Diocese of Gallup in New Mexico, here’s part of a letter from Bishop James S. Wall:

Let me say at the outset: I know this can be a contentious topic. To make changes to the way we pray can be difficult, especially when it comes to liturgical prayer. By explaining and advocating for this, I am in no way trying to disrupt the way the people of this Diocese pray. Rather, I am trying to open the treasury of the Church’s patrimony, so that, together, we can all experience one of the most ancient ways that the Church has always prayed, starting with Jesus and reaching even to our own day, and thereby learn from the “ever ancient, ever new” wisdom of the Church.

With that in mind, let me start with just a brief historical note. Essentially, we can say that celebrating Mass ad orientem is one of the most ancient and most consistent practices in the life of the Church—it is part of how the Church has always understood the proper worship of God. Uwe Michael Lang has published a book showing just this, entitled Turning Towards the Lord: Orientation in Liturgical Prayer and published by Ignatius Press. His extensive and thorough research shows this very fact: that, in the words of Cardinal Ratzinger, “Despite all the variations in practice that have taken place far into the second millennium, one thing has remained clear for the whole of Christendom: praying toward the east is a tradition that goes back to the beginning” (The Spirit of the Liturgy, p. 75). This means that celebration of Mass ad orientem is not a form of antiquarianism, i.e. choosing to do something because it is old, but rather choosing to do something that has always been. This also means, in turn, that versus populum worship is extremely new in the life of the Church, and, while a valid liturgical option today, it still must be considered novel when it comes to the celebration of Mass.

Allow me now to give a brief explanation of ad orientem or ad Deum worship. Prayer and worship “toward the East” (ad orientem, oriented prayer) “is, first and foremost, a simple expression of looking to Christ as the meeting place between God and man. It expresses the basic christological form of our prayer. […] Praying toward the east means going to meet the coming Christ. The liturgy, turned toward the East, effects entry, so to speak, into the procession of history toward the future, the New Heaven and the New Earth, which we encounter in Christ” (Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, p. 69-70). By facing Christ together at Mass, we can see how “[o]ur prayer is thus inserted into the procession of the nations to God” (ibid., p. 76).

Related: What happens when a parish adopts the ad orientem posture?

Deacon, look East: Serving my first Mass ad orientem

Ad orientem worship is thus a very powerful reminder of what we are about at Mass: meeting Christ Who comes to meet us. Practically speaking, this means that things will look a bit different, for at such Masses the Priest faces the same direction as the Assembly when he is at the altar. More specifically, when addressing God, such as during the orations and Eucharistic Prayer, he faces the same direction as the people, that is, toward God (ad Deum). He does so literally, to use a phrase dear to St. Augustine, by “turning toward the Lord” present in the Blessed Sacrament. In contrast, when addressing the people, he turns to face them (versus populum).

…I have decided that, since the recent solemnity of Corpus Christi, the 11:00am Sunday Mass will henceforth be celebrated ad orientem at the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Gallup.

This provides the faithful with the opportunity to attend the Mass in this way—indeed, in this way which is still approved and generously allowed by the Church. This is also a practice I would like to encourage throughout the Diocese of Gallup. I believe it is pastoral to offer Masses both ad orientem and versus populum, so that, together, we can all be exposed to the varied riches of the Church and Her prayerful history. With St. Augustine, allow me to conclude with this heartfelt prayer: in our worship, hearts, and lives, “let us turn towards the Lord God and Father Almighty, and with a pure heart let us give Him sincere thanks as well as our littleness will allow…. May He increase our faith, rule our mind, give us spiritual thoughts, and at last lead us to His blessedness, through Jesus Christ His Son. Amen.”

UPDATE: Some interesting history and background on this practice can be found in Wikipedia. Snip:

In early Christianity, the practice of praying towards the east did not result in uniformity in the orientation of the buildings in which Christians worshipped and did not mean that the priest necessarily faced away from the congregation, the meaning today commonly attached to the phrase ad orientem. The earliest churches in Rome had a façade to the east and an apse with the altar to the west; the priest celebrating Mass stood behind the altar, facing east and so towards the people. According to Louis Bouyer, not only the priest but also the congregation faced east at prayer, a view strongly criticized on the grounds of the unlikelihood that, in churches where the altar was to the west, they would turn their backs on the altar (and the priest) at the celebration of the Eucharist. The view prevails therefore that the priest, facing east, would celebrate ad populum in some churches, in others not, in accordance with the churches’ architecture.

It was in the 8th or 9th century that the position whereby the priest faced the apse, not the people, when celebrating Mass was adopted in the basilicas of Rome. This usage was introduced from the Frankish Empire and later became almost universal in the West. However, the Tridentine Roman Missal continued to recognize the possibility of celebrating Mass “versus populum” (facing the people), and in several churches in Rome, it was physically impossible, even before the twentieth-century liturgical reforms, for the priest to celebrate Mass facing away from the people, because of the presence, immediately in front of the altar, of the “confession” (Latin: confessio), an area sunk below floor level to enable people to come close to the tomb of the saint buried beneath the altar.

Anglican Bishop Colin Buchanan writes that there “is reason to think that in the first millennium of the church in Western Europe, the president of the eucharist regularly faced across the eucharistic table toward the ecclesiastical west. Somewhere between the 10th and 12th centuries, a change occurred in which the table itself was moved to be fixed against the east wall, and the president stood before it, facing east, with his back to the people.”This change, according to Buchanan, “was possibly precipitated by the coming of tabernacles for reservation, which were ideally both to occupy a central position and also to be fixed to the east wall without the president turning his back to them.”