With advances in automation and artificial intelligence, the future of work has become a significant area of interest and concern. In addition to important discussions about the future of various careers and income distribution, we have an opportunity to think about why we work.

Technological disruptions are not new to the workplace. But as more tasks become automated, it’s likely that some jobs will become obsolete, new jobs will be created, and most jobs will change. John Markoff describes this as a tension between artificial intelligence and intelligence augmentation: “Analysts look at the same Bureau of Labor Statistics data and simultaneously predict both the end of work and a new labor renaissance.” “Whether labor is vanquishing or being transformed,” Markoff concludes, “it’s clear that this new automation age is having a profound impact on society.”

The nature and details of this impact are unclear and open to speculation, which range from utopian to dystopian extremes. If you haven’t delved into this literature yet, you can save yourself some time by starting with Jill Lepore’s recent New Yorker essay, “Are Robots Competing for Your Jobs?,” and John Oliver’s recent commentary on automation.

Another good resource is Karel Čapek’s 1921 play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), in which the director of a robot production company has a dream “to transform all of humanity into a worldwide aristocracy. Unrestricted, free, and supreme people. Something ever greater than people.” One character critiques the director’s ideas for sounding “too much like paradise,” and pleads that “there was something good in the act of serving, something great in humility … there was some kind of virtue in work and fatigue.” The dream doesn’t work out: people cease being generative (literally), and then the robots rebel.

A future in which AI increasingly performs tasks previously done by humans requires educational and social support for new workers and workers in transition. As important as these issues are, we also should be asking more fundamental questions about the value and purpose of human work.

Dorothy L. Sayers challenged her generation during the Second World War to think about work not with a view toward compensation (“will it pay?”) but with a view toward value (“is it good?”). One does not work to live; one lives to work. Her answer to the question “why work?” is rooted in the doctrine of creation: humans are created to serve their Creator and others in work—work “is a medium of divine creation.” Sayers’s view of work can seem idealistic, even eschatological. Is the meaning of work found in our beginnings?

Yes, to an extent. In a previous post, I wrote about the technological prehistory of human work. Before we were human, we were technological—a species evolving with the help of tools and techniques. As humans, we have always been augmented by technology. One way to look at the future is as an extension of this evolutionary trajectory.

Miroslav Volf, alternatively, grounds work in the doctrine of new creation that leads “the present world of work toward promised and the hoped-for transformation.” Beginning with new creation means that a clearer meaning of work may be found—apocalyptically—in our end.

For Christians, the great image of the end is New Jerusalem. Brian Blount points out that this image of a “tangible, measurable, objective city” at the end of the Apocalypse “signals a salvific identity that is neither individualized nor spiritualized but concretized in the communal relationship that exists in an urban environment.” A follower of Christ, he concludes, “works with God to transform the world.”

Humans were, according to Sayers, created to work. According to Volf, we also were created to participate in new creation through our work. T. S. Eliot wrote that we may begin with the understanding that in our beginning is our end. But on the other side of that Friday we call good, we discover that in our end is our beginning.

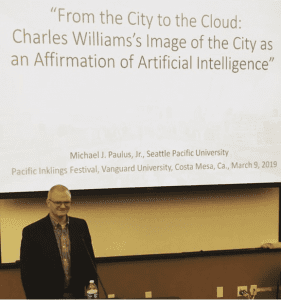

About the above image: The author presenting on Charles Williams’s image of the city (contra Jacques Ellul’s), Williams’s theology of technological work, and AI (photo taken by Sørina Higgins, March 9, 2019). Presentation slides available here.