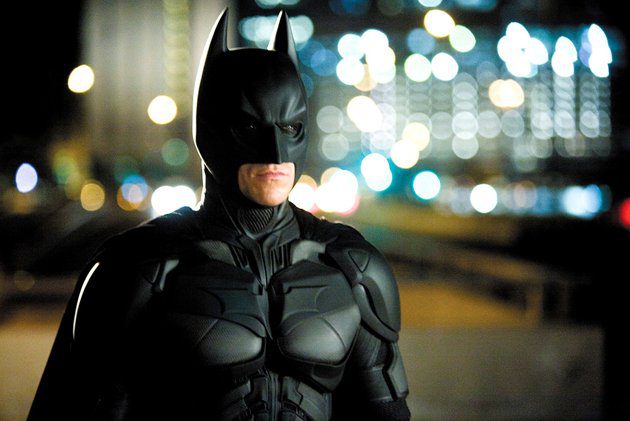

When The Dark Knight premiered in 2008, I declared it the best film of the decade (with The Lord of the Rings as closest competition). Now, with Christopher Nolan’s trilogy drawing to a close, how will the complete Dark Knight saga compare to Peter Jackson’s massive imagining of J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic story? I raised these questions in this review, first published at Purple State of Mind, in summer 2008.

With The Dark Knight‘s claims to box-office pre-eminence secured, the spin cycle begins. What does this hugely popular, amazingly resonate movie mean? What is the message amidst all the madness cruising through Gotham’s streets?

The Dark Knight is all about choices. Christopher and Jonathan Nolan embed this comic book universe with the contemporary question: how should we respond to terrorism? Will we suspend civil rights for the sake of order? What are the limits of interrogation? The Joker pushes Bruce Wayne to the brink of his moral code. Batman breaks ankles to obtain information. Do ethics hinder our effectiveness in fighting crime? The Joker is frighteningly free, dangerously untethered. He makes law and order attractive. Yet, he also points out how easily we adapt or rewrite our rules. What happens when our plans are derailed? Do we paint ourselves as heroes to rationalize carefully crafted schemes? The Joker exposes our tendency to justify our actions irrespective of the law. How much difference is there between a mobster, a corrupt cop or an accountant who fudges the books? Don’t vigilante break laws, too? This is about how the world (doesn’t) work.

Casual moviegoers may be shocked by the thematic richness of The Dark Knight. It is far more than an adrenaline rush (although there are plenty of dazzling tricks–sky hook, anyone?!). As Batman chases the Joker down a hole, we are all implicated in this increasingly dark crusade. Interrogation scenes reflect the haunting photos from Abu Ghraib. Will we abandon our moral precepts to gather evidence? Even more horrific are the suicide bombers created by The Joker. His false promises of future glory literally consign people into becoming ticking bombs. We’re snapped back to London and Spain, where a bomb may be planted underneath or even within anyone. It is easy to turn on each other. In a paranoid era, how do we retain our faith in people? Is goodness still viable? The darkness in Gotham threatens to overcome us.

Just when The Dark Knight seems to have exhausted the audience, Christopher and Jonathan Nolan trot out an old saw in act three. The situational ethics of the sixties gave rise to countless teachable moments about characters adrift in a lifeboat. If a cross section of humanity were caught in a dinghy with limited resources, who should live and who should die? And who gets to stand in judgment? This moral dilemma takes on surprising relevance in an age of wiretapping, torture and Guantanamo Bay. Are some lives worth more than others? Who deserves to be saved? Can’t we eliminate the wrong kind of people? The Dark Knight could have devolved into silliness comparable to the television show, “Survivor.” Who will be voted off the island or thrown overboard? Instead, The Dark Knight offers a surprisingly humane, redemptive conclusion, rooted in prayer and compassion. The Joker gambles on our innate selfishness and loses. Nolan defuses the forgettable fireworks we’ve come to expect from popcorn flicks with something even more amazing: good resisting coercive evil.

The Dark Knight may be the best film of this decade. (It has actually rocketed atop the IMDb list as the best film of ALL-TIME, before settling in at #8). It encapsulates all the conflicted feelings swirling around the war on terror. It burrows into our corporate soul and wonders what price victory. As the second part of a longed for trilogy, The Dark Knight stands alongside such troubling sequels as The Godfather Part II and The Empire Strikes Back. It is always darkest before the dawn. Fulfilling the promise embodied by his first features, Following and Memento, Christopher Nolan emerges as the most important director of his generation. I devote almost an entire chapter of my new book, Into the Dark, to Nolan. No one probes the human psyche with more depth or consistency. The cracked mirror he holds up in Insomnia, The Prestige, and Batman Begins convicts us. We are all duplicitous sinners. But Nolan doesn’t stand in judgment above us, but in conviction alongside us. He doesn’t talk down to the audience, but expects us to rise up, to examine the evidence, and come to the haunting conclusion that we are all murderers, thugs, and thieves. We’re all adrift in the same boat, searching for lifeline.

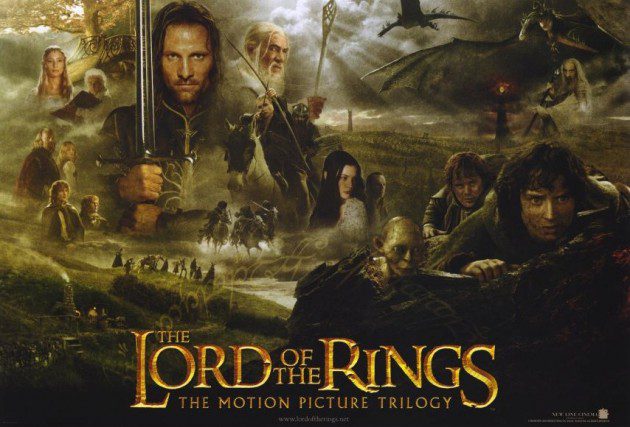

The main contender for finest 21st century film is Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. Both LOTR and The Dark Night offer mythic struggles riddled with temptation. Their action sequences are big, bold, and energizing. Both directors eke out a hard earned hope. Yet, Lord of the Rings looks effervescent and bright compared to Nolan’s Batman movies. While Lord of the Rings suggests that we can only resist evil as a community, bolstered by a fellowship of complimentary gifts, The Dark Knight chooses a more solitary path. He is willing to be hated, rejected and despised for the sake of society. Perhaps they represent the two moods/moments which divide the war on terror.

Lord of the Rings summarizes the first half of this decade. It offers clarity regarding good and bad, heroes and villains. It is rooted in J.R. R. Tolkien’s vision and experience of World War II. War exacted a horrible price, but good still triumphed over evil. Peter Jackson’s Rings trilogy reflects who we thought we were after 9/11. The enemy was clear, the world’s outrage uniform. But when we rushed into Afghanistan and especially Iraq on trumped up evidence without international support, we crossed over into The Dark Knight’s vigilantism. We poured money into new technology, placing our faith in firepower. It looked like mission accomplished. But we attacked as less than a fellowship. Without enough outside accountability, we descended to the level of our enemies. With our plans for quick succession derailed, Iraq edged toward chaos. The Joker drags Batman into a similar quagmire.

An air of dread dominates The Dark Knight. It taps into our fear regarding random terrorist acts. It reminds us of the creepy power of handheld video. One destabilizing force sets off panic in the streets. We all become ticking bombs, likely to explode in public spaces. There is no rationale for this kind of evil. The Joker is beyond greed. He delights in death. As Alfred reminds us, “Some men just want to watch the world burn.” The Gotham police and district attorney Harvey Dent are rooting out corruption, building a case against organized crime. They battle a multi-national, multi-racial crime syndicate that extends from America to Asia. But the Joker breaks even the criminal code, stealing from the mob. What happens when there is no honor among thieves? Perhaps vigilante justice is better when confronting disorganized crime. Batman adopts methods that the authorities cannot. Our problems in Iraq may stem from our strategy. A nation attacked a nation in order to catch a movement. We sent an army to combat isolated individuals. The Dark Knight reflects post-Iraq realities. All are fallen. Most are implicated. Few are spared. The stain of sin and duplicity washes over humanity.

The weakest link in The Dark Knight may be Batman himself. We see him ruminate over the ashes of a smoldering building, but he bottles up most of his struggle. There are hints of personal guilt and responsibility in his refusal to concede to the Joker’s demands. Does Batman really believe there is blood on his hands? While Batman Begins focused upon his backstory, The Dark Knight shifts to the origins of Two Face. Harvey Dent is free to vent his emotions and act out on his loss. But the famed bachelor Bruce Wayne must put on a different mask in public.

With Batman hidden by a cowl, Lieutenant Jim Gordon occupies the moral center of The Dark Knight. Like the soldiers who serve in Iraq, his family bears the brunt of the battle. They must deal with the long nights of waiting, wondering, and worrying. Gary Oldman brings a weary determination to Lt. Gordon. He is an everyday cop, familiar with the compromises inherent in the force. When a successful campaign bumps him up to police commissioner, he takes the job out of duty rather than joy. Gordon knows the cost of fighting criminals. It is long, protracted struggle, taking a toll on himself and his family. We feel the weight of his world.

So how do we deal with our fallenness? What solution does Christopher Nolan propose? Bruce Wayne brings his frustration to Alfred, “People are dying. What would you have me do?” Alfred snaps back, “Endure.” But such endurance involves much more than survival. We’re challenged to remain decent in an indecent world. Such choices come at considerable cost. The Dark Knight suggests we can die as a hero or live long enough to become a villain. Neither option looks particularly attractive. Both echo the sacrificial path of Jesus, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King. Their non-violent tendencies got them killed. By the conclusion of The Dark Knight, Gotham’s hope resides in a watchful protector, a silent guardian. He will suffer so that they might retain a hope, a promise, a purpose. Gotham may long for a white knight to save them, but for now, a Dark Knight must suffice.

Check out all the Patheos bloggers’ thoughts on The Dark Knight Rises here.