When I have been asked to name my favorite novel, I always answer Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Not because it is has the most riveting plot or the most pleasant story, but because it burrowed into my soul and built empathy into my being. Never before had I felt so immersed in the mind of a protagonist, particularly one whose life experience was so different from my own. While I can never know what it feels like to be an African-American, Ralph Ellison put me inside his head in ways that shook me to the core. Sixty years after publication, it remains a piercing vision.

I read Invisible Man as a recent college graduate, teaching English in Japan. Perhaps my setting enhanced my appreciation. Being a minority does something to you. Not understanding the cultural codes and assumptions puts you on guard. You are hesitant to speak. You try to avoid being called upon. You step back, hoping not to be noticed. In an island and culture that was so uniform, my skin marked me as different. I stood out so much on the subway that I wanted to be invisible. Amongst the first Japanese words I learned (because it was so often uttered behind my back): “Henna gaijin”—“Strange foreigner.”

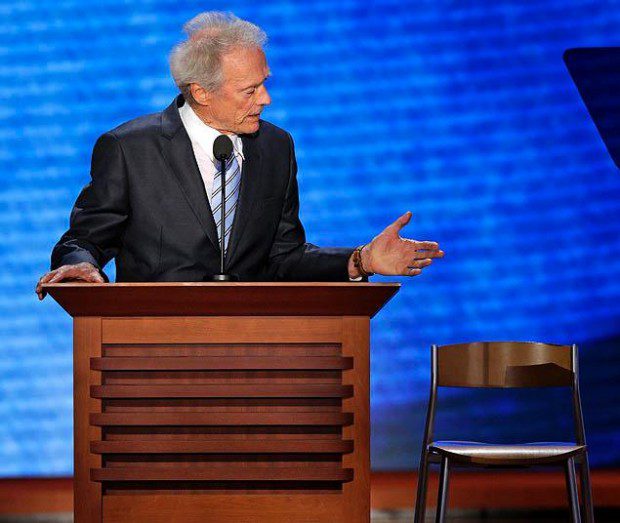

Tonight, I watched one of the most famous and beloved American icons treat the President of the United States like an Invisible Man. It was shocking, appalling, tragic, freakish, and weird; amongst the most jarring moments in (televised) American political history. And I am horrified that for all the historic and symbolic importance of Barack Obama’s victory in 2008, tonight, he was talked down to and rendered invisible. While I am deeply committed to free speech and dissent, the sight of a white man figuratively putting a proud black man in his place is nevertheless disgusting. And twice putting the most offensive profanity in his mouth is nearly unconscionable. Harry was definitely ‘dirty’.

I am familiar with the origins of this one-sided comedic routine from the days of Bob Newhart. These faux conversations can be quite funny. But I never recall the Button-Down Mind of Newhart using it to demean or disempower an actual person. In his famous “Abraham Lincoln vs. Madison Avenue” routine, the joke was on Madison Avenue more than the President. His humor was aimed at the absurdities we all face. Newhart played the beleaguered driving instructor or the sadistic bus driver, dealing with clients that refused to cooperate. The familiarity of the situation allowed us to fill in the blanks and laugh at the truth presented.

Many were entertained by Clint Eastwood’s riff on Newhart’s humor. But if they had read Ralph Ellison’s classic 1952 novel, then perhaps their perspective would have changed. And laughter might have turned to tears. David Denby recently noted how timely Ellison’s novel remain, even finding parallels in Obama’s autobiography, Dreams from My Father: “There was a trick somewhere, though what the trick was, and who was doing the tricking, and who was being tricked, eluded my conscious grasp.”

Clint Eastwood told us far more about himself than about the President. And while Mitt Romney and the Republican convention planners may attempt to distance themselves from Eastwood’s performance, it is a sad reflection on their lack of judgment. I expected better (talk about an eternal optimist!). I really didn’t want to write about politics during this election cycle. Neither candidate has impressed me as up to the enormity of the task at hand. And of course, I’ve seen so much vitriol exchanged across our social networks, that I feel no compunction to enter the fray. But this is too ugly and embarrassing to ignore. Evidently, we, as Americans, still have plenty to learn from Ralph Ellison. I conclude with his Prologue:

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe, nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surrounding, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.