Despite what many critics have proclaimed, Inside Llewyn Davis is not the best film of the year. It is not the best film of the Coen Brothers’ career. It has remarkably melancholy music, but it doesn’t offer more than one recurring note. It is dark; really dark. Filmmakers (and especially cinematographers) love to get deep blacks on their images. Inside Llewyn Davis has great blacks. It makes evocative use of the dark shadows in the corners of every scene. They hang over the Gaslight Club, circa 1961 and the alleys off MacDougal Street. And a dark cloud looms over Llewyn Davis’s head in each and every scene. You see, Llewyn Davis is doomed to failure. He always chooses the wrong thing, says the wrong thing, does the wrong thing. He throws out things he should have kept. Spouts out thoughts he should have kept to himself. Drives past places he should have stopped. Like his decrepit father, Llewyn “shoulds” on himself.

Thankfully, Llewyn Davis is a good singer. Because otherwise, this trip Inside Llewyn Davis would only be horribly depressing. The soundtrack, produced by T-Bone Burnett, contains a fascinating mix of vintage folk songs and evocative originals composed for the film. It reminds us of the mournful aspects of folk music, the old sad songs of Ireland, Wales, and England. The multiple versions of the traditional ballad, “Fare Thee Well,” build a sublime power as we understand more of what’s haunting Llewyn.

The songs also show what a dollop of American optimism did to the troubadour tradition. The absurd recording session of the space-age satire, “Please Mr. Kennedy” (featuring an earnest Justin Timberlake!) is the bright spot of the movie. But is this scene enough to endure all of Llewyn’s grief?

Making the best part of Llewyn Davis (the person and the movie) his music is evidently the point. Sad sacks can create great music; and maybe the sadder the sack; the greater the music. It is a cautionary tale for aspiring artists, musicians, and dreamers everywhere. “Don’t get your hopes up on being discovered or appreciated or having an audience because industry execs and agents are thieves who are only in it for the money.” Life is suffering. Prepare to suffer for your art (unless you’re Bob Dylan or the Coen Brothers).

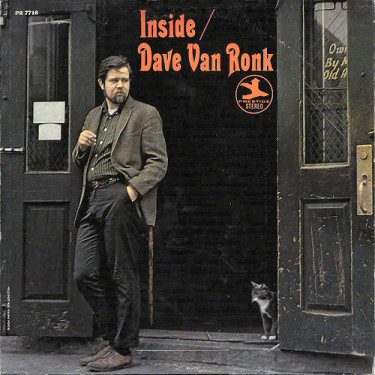

My quarrel with the Coen Brothers is that they don’t seem to have been true to the spirit of the age. It isn’t enough to get the cable sweaters of the Clancy Brothers just right. I understand that Inside Llewyn Davis is rooted in real singers like Dave Van Ronk who never crossed over into mainstream acceptance. It casts a cynical glow upon impresarios like Moe Asch of Folkways Records and Albert Grossman and his Gate of Horn in Chicago.

Standing in for Grossman, F. Murray Abraham provides the one laugh-out-loud line in the film with his stark appraisal of Llewyn’s music. The business savvy of Grossman undoubtedly made him millions. He made (wealthy) stars of Bob Dylan and Peter, Paul, and Mary and punished artists who didn’t comply with their wishes (probably pocketing their royalties). But what about the genuine advocacy and preservation work of Alan Lomax and Moe Asch and Folkways whose recordings formed the cornerstone for the Smithsonian’s collection? Such an essential treasure trove of the American musical experience was gathered thanks to their efforts. Inside Llewyn Davis never gets beyond the central truth that life is hard, hearts will be broken, and jazz musicians with a heroin habit will die tragically. The rapturous reviews for Inside Llewyn Davis reveal far more about the critics and their worldview than the film. Inside the Coen-friendly, hipster El Lay, Arclight theater where I saw it, the laughter was sparse in this bummer of a movie.

The Coen Brothers never get inside the motivations of the people who wrote songs of hope and change rooted in America’s lofty aspirations. (Read this telling interview from the Village Voice with Dave Van Ronk’s widow). They’ve crafted a paean to the folk scene before it turned into an enterprise. However, I’m not sure it is profound or true to suggest that Peter, Paul, or Mary were craven, empty, or stuffy. I’ve met and chatted with Peter Yarrow on several occasions and I’ve also found him remarkably personable, passionate, and generous. He still believes in what he sings even if the Coen Brothers don’t (or never did). Instead, they’ve chosen to pour their dour, dark view of humanity upon one the most progressive eras of pop music. It is almost like releasing Inside Santa Claus just in time for Christmas—how to drain the joy out of childlike wonder. (And don’t get me started on the one note portrait of the only significant woman in this pre-birth control era, the profane Jean. What a long way from the robust pregnant officer embodied by Francis McDormand in Fargo).

I get that like all their movies, Llewyn invites multiple viewings. They scatter a few clues to reading the film—“Llewyn as the cat, the cat as Ulysses, the film as a take on the James Joyce’s Ulysses which thereby links it back to their earlier musical take on the Odyssey, O Brother Where Art Thou?” But by the time I do all that, I am reading a thesis, rather than watching a movie. That’s not cinematic delight. That’s a puzzle box built for the creators’ enjoyment. Like in their earlier Barton Fink, I don’t feel invited into their private jokes. I’m on the outside, happy for them; sad for me, and the audience.

I have been a fan of the Coen Brothers since their debut feature, Blood Simple. I chortled through Raising Arizona, reveled in The Big Lebowski (in its original theatrical run!), and marveled at Fargo. I laughed a lot at Intolerable Cruelty while others scoffed. They deserved the Oscar for No Country for Old Men, for demonstrating where unmitigated greed will get you. It was the perfect film to arrive before the Wall Street crash/housing loan debacle. Yet I also recognize that they are fallible. Anyone who suffered through The Hudsucker Proxy realizes this. And while some thought Barton Fink worthy of winning the Cannes Film Festival, I found it to be a cruel joke on the audience. In my application to the University of Southern California’s film school, I skewered that “Barton Sinking Feeling.” While it was a risk to diverge from critical opinion, I couldn’t give the bleak nihilism in Barton Fink a pass. They didn’t give the audience much in exchange for our time and money (although I’m sure they enjoyed creating Barton Fink and found it satisfying to their own tastes/desires).

I admired A Serious Man because they took the story of Job to its logical conclusions. They updated what that twisted tale would look like played out with a college professor. It felt rooted in their own experience of the 60s as children of an academic. I understand that some people suffer more than their fair share. Or at least that life can be unfair. But I don’t feel like the Coen Brothers have told the whole truth in Llewyn Davis, or maybe they’re too content with a half-truth. Why haven’t they celebrated their own success in getting their stories onscreen? Does Llewyn’s story mirror their experience? I guess it takes courage after several Oscars and millions in moviemaking fees to still say, “The people who run the entertainment business are awful, greedy people with no taste.” Llewyn certainly has a talent for biting hands attempting to feed him. Maybe that’s the connection we’re supposed to make.

For all of my non-success as an artist, I don’t curse the business or consider everyone else a fraud. I don’t see how Llewyn’s disdain for humanity somehow fuels his compassion as a singer. I share the Coens misanthropic tendencies and also write with a satirical bite. I believe we are fallen, fallible, and prone to self-destruction. Yet, I can’t really make that my reason to create. Maybe I just missed the beauty of Llewyn carrying on in the face of losing a partner by couch surfing, impregnating women, and borrowing money to pay for abortions from friends that he never intends to repay. Perhaps we can’t expect the Coens or Llewyn to sing us a happy ending. Sometimes it is helpful to hear cold, hard truths. Do we really need to slather them upon one of the last times we all sang folk songs together?