Theologian Sallie McFague has died at the age of 86. Her body of work has inspired me as a preacher and teacher, as an ecofeminist, and as an author.

After graduating seminary in 2000, I began my first call as an associate pastor at a thriving 700-member suburban congregation. Two years into this ministry I was alarmed at the feelings of burn-out I was experiencing so early in my career. One afternoon I sat in the office of my counselor bemoaning the predicament in which I found myself. Why did God call me to a ministry of endless demands? Why was God pushing me in a relentless drive for church growth at all costs?

My counselor listened. Then she wondered out loud if my situation had as much to do with my concept of God as it did with my ministry context.

She asked me to describe how I thought about God.

“He expects perfection,” I said. “He’s watching everything. He’s relentless. I know I should be able to experience God’s grace, but I can’t. It feels like nothing I do is ever enough for him.”

My counselor noted that my pronouns for God were masculine. She asked if perhaps I should look for another model of God. I was nonplussed. The thought of finding other ways to conceive of God had never occurred to me. I didn’t think this was even possible, let alone allowable.

That conversation began a quest to explore alternative ways of thinking about God that are intentionally different from the image of God I had grown up with and which had accompanied me through seminary and into ministry. My seminary training had not introduced me to any contemporary feminist theologians, nor had it challenged me to articulate my faith in non-masculine terms.

It was only after being in parish ministry for several years (and experiencing the life-altering process of being pregnant and giving birth) that I began to explore non-gendered and female imagery for God within scripture. One of the most pivotal scholars in my transformation was Sallie McFague.

Sallie McFague, theological pioneer

Born in 1933 in Quincy, Massachusetts, Sallie McFague was among the “first wave” of feminist theologians. Her pioneering work in theological language helped to upend traditional interpretations of religious experience and create liberating cracks in the walls of patriarchy. McFague’s academic interests first formed around a love for literature and the English language.

Her spiritual and religious questions, however, drew her to Yale Divinity School where she earned her Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1959. At Yale she also received a Master of Arts degree in 1960, followed by her Ph.D. in 1964. This resulted in her doctoral thesis, Literature and the Christian Life, demonstrating that McFague had begun to integrate her love for language and literature into her theological work.

McFague’s work has focused on liberating and healing humanity’s relationship with Earth, with God, and with those segments of humanity most abused by our patriarchal systems – women and those most marginalized. Her books showed me how to reinterpret Scripture and question traditional interpretive foundations. She challenged me to recontextualize my faith and call into question accepted power structures. Her writings guided my quest for expanding my concepts about the Divine and offered methods and practices for preaching justice, liberation, and healing.

A foundational voice for ecofeminist theology

McFague’s work was driven by the urgency of the ecological crisis and the oppression of women, as well as the religious and theological structures that reinforce these destructive tendencies. Ecofeminist theologians advocate for the simultaneous liberation of women and nature. Her writings offer an inspiring model of struggle for liberation, intellectual prowess and clarity, and hope for a people and planet desperately in need of the transformative love of God. She wrote nine books over the course of her life. I’ll focus on just three here.

Metaphorical Theology

In Metaphorical Theology: Models of God in Religious Language (1982), McFague insisted that the task of deconstructing and reconstructing the models by which we understand our relationship with God and the world is imperative. She sought to “understand religious/theological language in terms of metaphors and models. Religious language is largely metaphorical, while theological language is composed principally of models” (193).

For McFague, models are the means by which we build our religious metaphors and structure our spiritual and ecclesiastical realities. McFague’s revelatory insight was that all theology is experimental, even the Scriptural and traditional forms that have been codified and established as the “norm.” Thus, her method was to first critically examine traditional models of God in order to deconstruct their literalism. Then she would return them to their proper place as metaphors which “are not descriptions but indirect attempts to express the unfamiliar in terms of the familiar” (193).

McFague proposed alternative models that are based on the parables of Jesus, which she saw as being primarily relational.

These models more accurately reflect the “personal, relational images [that are] are central in a metaphorical theology – images of God as father, mother, lover, friend, savior, ruler, governor, servant, companion, comrade, liberator, and so on” (20). She went onto to show how the metaphorical construction of God as “Father” is, in fact, an idol, because it replaces worship of the truly unknowable God with a model that serves only to reinforce patriarchy.

Further, she stated that if we lose sight of our religious context, our language “will become irrelevant, for the experiences of many people will not be included within the canonized tradition” (20). This is especially true for women who are excluded from full participation in those faith communities where the only models for God are paternal, patriarchal, and male-dominated.

“Whoever names the world owns the world,” she observed, and females are already born into a linguistic world that excludes them (8). Therefore she encouraged a deliberate effort to engage in new naming as well as changes in language that reflect women’s experiences of themselves and their world. Not only does this serve to upend the idolatry of traditional God-talk, but adds dignity to the personhood of women and affords them the power to name themselves even as they name God.

Models of God

McFague’s work in Models of God (1987) was to remythologize the relationship between God and the world. She performed “thought experiments” using alternative models of God as mother, lover, and friend. McFague stressed that the patriarchal models, as contrasted with the models she was presenting, are not to be dismissed outright as “wrong,” but are to be judged as to whether they are appropriate for Christian faith today (viii). In other words, what models are most appropriate, given our current nuclear and ecological crises?

McFague did caution that metaphors can only take us so far. The models eventually waver and falter when pushed beyond their limit, and we are reminded of their “nonsense” component, the “is-not” part of the metaphor. Nevertheless, for the mother metaphor, her point is true that “there simply is no other imagery available to us that has this power for expressing the interdependence and interrelatedness of all life with its ground. All of us, female and male, have the womb as our first home, all of us are born from the bodies of our mothers, all of us are fed by our mothers” (106).

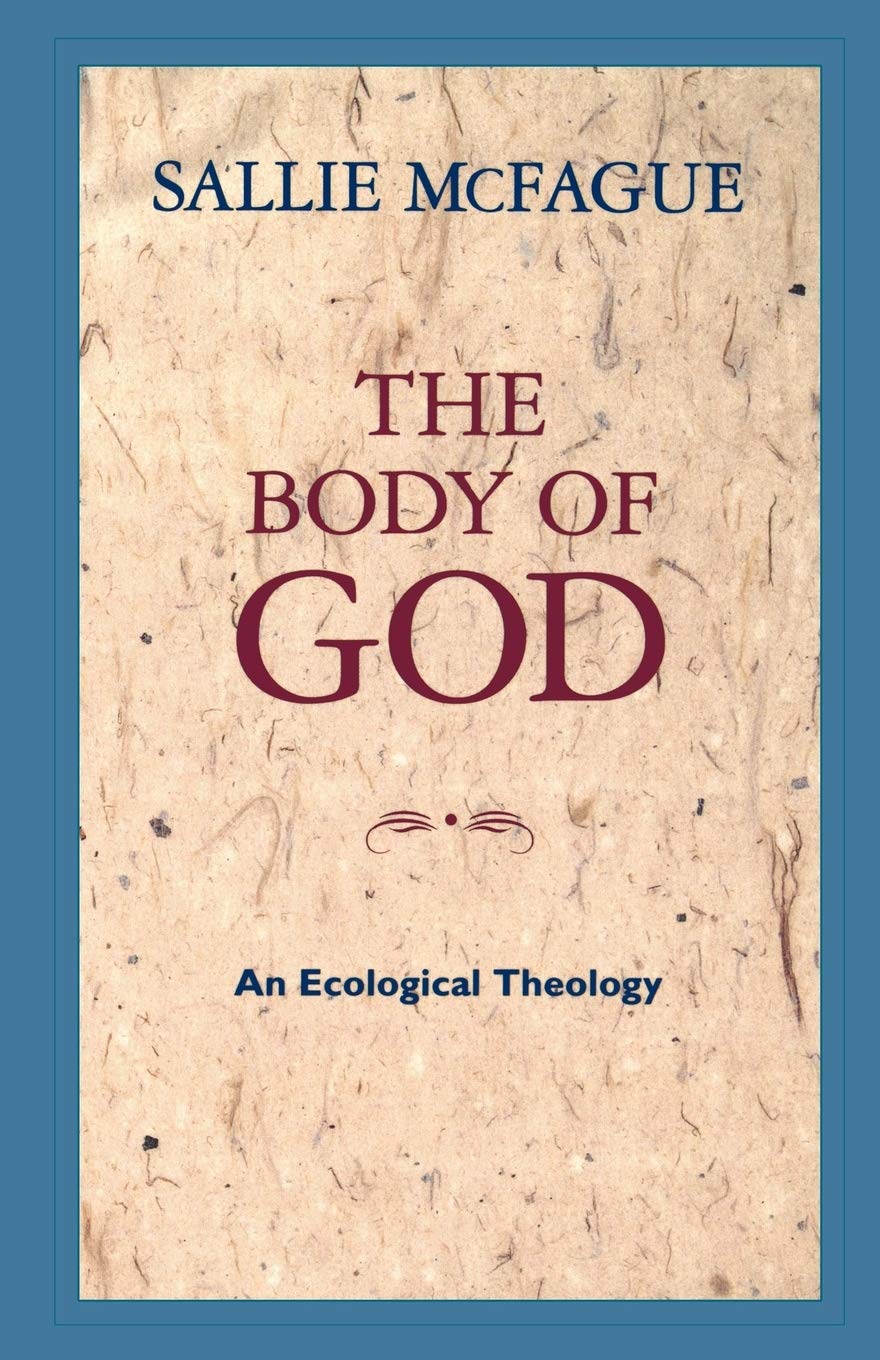

The Body of God

The issue of the extinction of life had taken primacy for all theological reflection for McFague in writing The Body of God (1993) and the books that followed. She proposed the model of the body for an ecological theology. This model is not based on the human body, because that would lead to a hierarchy of the head over the rest of the body parts. Instead, it is the body of the Earth – God’s chosen embodiment. This, in turn, includes all bodies: mountains, oceans, forests, insects, birds, and humans.

This model links us with Creation in a very intimate way and insists that all bodies have value. This, in turn, fosters an orientation towards justice.

McFague imagines God as the panentheistic, inspirited body of the universe, while also retaining God’s transcendence. This model of embodiment can lead to reorienting ourselves and how we see the world. It can transform our vision from a top-down, dualistic, utilitarian paradigm to that of belonging to and with Earth, loving, respecting and protecting it.

Her purpose in this book, as in previous works “is to change sensibilities, change the way voters, consumers, and organizers engage in political and economic action, from an individualistic, short-term profit mind-set to one that takes the broad view and the long view – the well-being of the planet as its foremost consideration” (11-12). McFague believed that changing life-styles is insufficient without a change in what we value. Thus, her task was to put forth models that will help us think differently so that we might act and behave differently.

Ecclesiastically, this embodiment theology involves the church being a sign of the new creation and the in-breaking of the new vision.

Churches are the place where people can experience this “de-centering” from arrogant anthropocentrism and androcentrism to a “re-centering” on Christ’s concern for oppressed bodies, most notably female, child, poor, non-human and nature bodies. McFague’s hope for the church rested on its ability to create organic communities which embody and live out concern for the basic needs for all bodies on Earth – as well as Earth’s own body. “Where the new vision of the liberating, healing, inclusive love of the embodied God in the Christic paradigm occurs, there is the church” (206).

The power of theological imagination

One of the most important things I gained from Sallie McFague’s books was a deep understanding of why using female imagery for God is not only allowable, but necessary. I felt that I was being given permission to conduct further “thought experiments” and imagine even more metaphors for God.

For example, what would it mean to speak of Jesus as “daughter”?

What would it be like to call Jesus not just “Son of God,” but “Daughter of God”? If Jesus is to be imaged as the vulnerable, innocent, crucified human being, what more fitting human entity is there than that of the human daughter, who in many parts of the world is unwanted because of her gender and often killed or abandoned at birth. Or subjected to genital mutilations. Or denied access to education. Or raped and shamed into suffering silence. Or readily sacrificed on the altar of war. So many of our daughters are “crucified” daily, hourly. Wouldn’t it be shockingly appropriate to image Jesus as a young female human? McFague’s books led me to ask these questions.

Over the past ten years of reading McFague’s books, new visions of God began to appear in my dreams and in my mind’s eye as I prayed.

Most intriguing to me were the images that arose from nature, such as a mother bear, gardens, and large earth-colored women – all of which showed themselves as symbols for God. These dreams and visions coincided with my growing concern for ecological issues, particularly within the context of the Church. In my ministry and eventually my own writing, I have echoed McFague’s call for the church – and especially preachers – to address the global environmental crisis. [See Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit, Chalice Press, 2015.]

I am grateful for Sallie McFague’s scholarship and her mentoring of a generation of theologians who can now carry on her work.

One of her students was Emily Askew who studied with her at Vanderbilt Divinity School, and who now teaches theology at Lexington Theological Seminary where we are both members of the faculty. Emily has taught hundreds of students the importance of understanding the power of theological language – power that can be life-giving but also oppressive if not handled with an orientation toward liberation, justice, and compassion. Together, Emily and I have used McFague’s work to teach our students how to appropriately use theology in sermons.

We have even brought McFague’s theology into the realm of religion and science fiction, referencing her work in our analysis of the Blade Runner films. In our article “What I’ve Seen with Your Eyes”: Relational Theology and Ways of Seeing in Blade Runner, we draw insights from McFague’s book Super, Natural Christians to help us make the case that the films are extended metaphors that provide a window on our own dystopian present. McFague, as well as these films, present us with choices as to how we will see the world and respond to the ecological and humanitarian crises already upon us.

Thank you, Sallie McFague.

Thank you for your theological courage, your commitment to the joint liberation of women and nature, and your insights into how we think about and articulate our “God-talk.” You have expanded my mind and re-introduced me to God in ways I had never known were possible. May you find rest and peace in the Body of God.

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/

Read also:

Creation-Care Preaching and the Theology of Sallie McFague

From Eco-Crucifixion to Eco-Resurrection

What Toni Morrison Taught Me About Racism in Her Book Beloved