David Russell Mosley

3 March 2014

On the Edge of Elfland

Beeston, Nottinghamshire

Dear Friends and Family,

Over on Christ and University, Matt Moser has been doing a series on the difficulties of teaching Dante. In his most recent post Moser notes that a significant issue in reading Dante is his cosmology which we no longer share on a broad societal level. This is an issue one often sees when reading Ancient and Medieval literature. In a sense, this is precisely what C. S. Lewis seeks to address in his The Discarded Image. The medievals, Dante, thought differently than we do about the way world works. One of the most common cases of this is an issue over spontaneous generation. The ancients and medievals thought flies came from decaying meat, spontaneously, or, usually, through some juxtapositional of the Zodiac.

This, however, is not the kind of problem we’re dealing with in Dante, nor is it the main problem we deal with in most of the Ancient and Medieval writers. Instead, as Moser notes, it is an issue of enchantment, or even more, an issue of seeing the Universe as a Cosmos (which means order). Moser writes,

‘This is the challenge of reading Dante. His cosmic imagination is difficult to apprehend because we inhabit an a-cosmological, disenchanted world. But more importantly, this is the challenge of Dante: “See the world you inhabit in this way,” he bids us. “To see order is to see goodness; to see harmony is to see beauty. To see goodness and beauty is to see truth. To see truth is to behold God.”’

Moser then connects this to education as such. In a cosmological understanding of education all the branches of the University are connected, they interpenetrate one another. But this is not the way we view education or the Cosmos. So it causes Moser to ask, ‘Is there a way to forge a cosmic imagination in our students given the a-cosmological world we inhabit today?’

I certainly do not wish to pretend that I have the one answer to this, the one solution that will fix all of education and our disenchanted vision of the universe. However, I think an aspect of the answer is in the problem. You see, the post is about the difficulties of teaching Dante, yet teaching Dante is one of the solutions to this problem. To put it more frankly, in order to get students to understand a cosmic and enchanted vision of the Universe we need to teach them about thinkers who have a cosmic and enchanted vision of the Universe. Even more so, if we agree with those thinkers, as Moser and I do, then we need to model that vision.

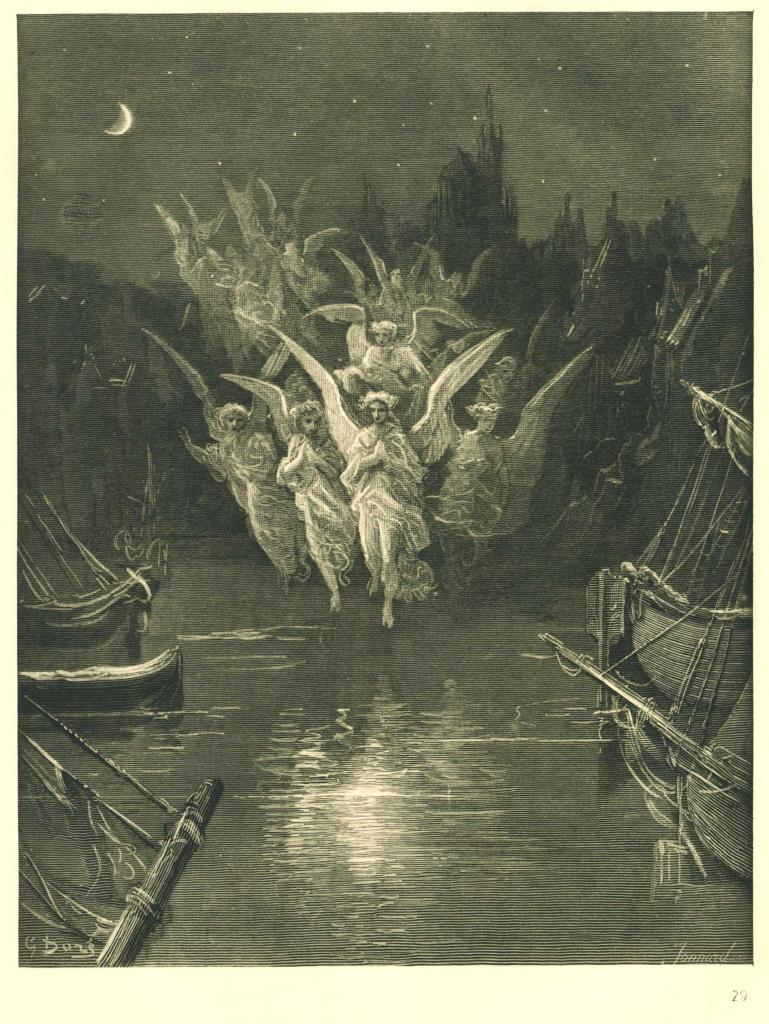

There are perhaps two things for which I am most frequently criticised here at Letters from the Edge of Elfland. The first is a jumble of my relatively theological conservatism (meaning I think Jesus is really the Son of God and the Bible is the word of God, etc.) and my qualified support of thinkers like John Milbank and the school of theology known as Radical Orthodoxy. The other critique, however, is based on my writing about things like Faerie, and King Arthur, and Enchantment. Nevertheless, I won’t stop precisely because this is the vision of the world our Christian forebears had, not always couched in the terms I have inherited from the Medieval and Romantic British, Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norman, and German traditions, but it was nevertheless a world where miracles were possible by the grace of God. It is a world where angels existed, as did demons. It is a world where God became man and now bread becomes flesh and wine blood. It is a world where humans can become gods or devils, but only by grace or its rejection. I think there are many ways to lead students to this kind of understanding (or at least to understand that this is how Dante et al., saw the world): not least of which are the reading and writing of fiction (especially fantasy), and reading the Ancients and Medievals themselves. However, to lead students to an even deeper understanding of the Cosmic vision of the Universe is to live it and to live it, unashamedly, in front of them.

Sincerely yours,

David Russell Mosley