David Russell Mosley

![]()

Advent

3 December 2015

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

As I continue to apply for jobs, applying for nearly three for every one I don’t get, I can’t help but reflect on what it means to be a theologian. Whenever I meet new people and they ask the inevitable question, “What do you do?” I always end up answering, somewhat bashfully, “I’m a theologian.” It was easier when I was still working on my PhD. I could just tell them that I was a PhD student in theology. But I’m not anymore, and that complicates the matter. After all, I don’t have a full-time job teaching theology. So I’m not a professional theologian in the sense that I get paid regularly, and enough to make a living, to teach theology. I remember in undergrad there was a professor in our seminary, Dr. Bob Lowery, who wrote once concerning what it means to be a scholar. Did it mean publishing journal articles, writing many books? Did it mean having a PhD or a teaching position at a university? Or did it mean being something more, something about being driven to learn and research regardless of whether one had met all the “proper requirements.” Dr. Lowery seemed to think it was the latter far more than the former. He thought that being a scholar was something much deeper than having a PhD and writing books and teaching at a university. But this is precisely what causes me to wonder what it means to be a theologian. I have academic training, the highest you can get, but does that make me a theologian? I think the answer is both yes and no. Let me explain.

Evagrius of Pontus, a fourth century theologian who is sometimes frowned upon in Western Christian circles has written, “If you are a theologian, you will pray truly. And if you pray truly, you are a theologian” (Treatise on Prayer, 61). So there is a sense in which every Christian is called to be a theologian. Being a theologian, in this sense, is one who is dedicated to life in Christ and the contemplation of the Holy Trinity. Even that can sound daunting to many lay Christians, but if you pray, you are a theologian, you are engaging in theology because you are engaging in thinking about and even talking to God. Yet even within this understanding, there are clearly some who spend more of their time engaged with thinking about and communicating both about and to God. There are levels, gradations, of being this kind of theologian. But these gradations are not inherently tied to education. No one would deny that St. Anthony was a great theologian, but he wrote no books and had little to no formal theological training. Nevertheless, St. Athanasius views Anthony as his superior both in the faith generally and as a theologian, which is why St. Anthony was appealed to during the Council of Nicaea.

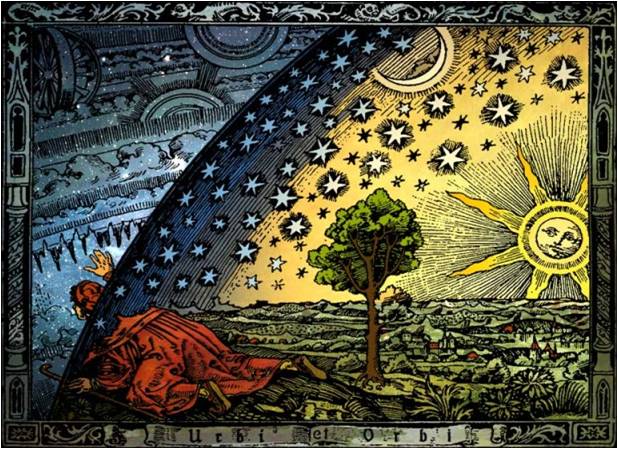

So if every Christian is a theologian and this isn’t necessarily tied to formal education, what does it mean when I call myself a theologian in the same way a cleric might call him or herself a priest, a vicar, a parson, a preacher, or a pastor? Here I have to introduce the language of vocation. Today vocation has typically come to mean training in skilled labor. This is why we have “vocational schools” which train people to be electricians, plumbers, mechanics, etc. (worthy and wonderful things). Other times it simply means the career path one has chosen. But originally, to have a vocation meant to have a calling from God to a certain way of life (the priesthood, monasticism, etc.). The word vocation itself comes from the Latin vocare: to call. I believe that I have a vocation to be a theologian, and this required for me formal and academic training.

I remember having some interactions with a former student at the University of Nottingham. He had trouble with some of the theologians in our department who often focused on issues he determined not strictly theological but philosophical (that’s as specific as I care to be, but I’m sure many of you can figure out the kind of stuff I’m talking about). He once told me that he’d rather pray in the gutter with me than read the work of some of our theologians. The Philokalia was his primary guide for what it meant to be a theologian. I don’t want to denigrate some of these opinions. Praying with the downtrodden is an immensely holy thing to do, and there are worse guides for one’s spiritual and theological life than the Philokalia. However, my issue was that this student had no room for academic training which included philosophy and critiquing modern society. He had no real room for theology as an academic discipline. And while I am sympathetic that there is a kind of theology which does not require academic training, and firmly believe that there is another kind that does.

One of my PhD supervisors, Simon Oliver, has two sayings that I often return to. He says that we know we are a royal priesthood because there are priests, that is that there are a class of people set aside for the priestly office. Similarly, he says that we know the world is sacramental because there are sacraments. The particular instantiation of the latter, priests and sacraments, allows us to understand the general instantiation of the former, royal priesthood and the sacramental nature of the cosmos. I think this applies to theologians as well. We know that all Christians are called to be theologians because there are theologians. We need people set apart to spend their lives studying theology, studying the deep things of God and his creation, for in this way can we understand that all Christians are called to some level of being theologians.

I do want to make one caveat here before I conclude. I want to return to Evagrius. Prayer, that is an active “devotional” life, and by that I mean a life of prayer and contemplation, a life of worship of the Holy Trinity, is necessary to be a theologian of any stripe. If that is missing, then one is certainly not a theologian, at least not in the Christian understanding of that word. One might study religions or a particular religion or even doctrines, but if one is not living a life of worship, participating in the rites and rituals of the Church (whichever tradition) then one is not a theologian. Another former professor of mine once told me that he never trusted, and nor should I, a theologian who doesn’t pray. I think there is much wisdom in this and the history of Christianity would certainly agree.

So, if you and I have never met and one day we do and you ask me what I do, I will tell you that I am a theologian. It has become as fundamental to me as being a husband and a father. Part of that is simply because I am a Christian and part of it is because I have trained and worked and continue to read and study and write. I am a theologian. I am a theologian because I pray. I am a theologian because I have studied to be one and continue to study. It is my calling, my vocation. At least for me, but I think more broadly as well, this is what it means to be a theologian.

Sincerely,

David