David Russell Mosley

Eastertide

31 March 2016

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

So I’ve recently taken the plunge and started reading Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age. For those unfamiliar with Taylor and/or this work, Taylor is a Canadian philosopher and is professor emeritus at McGill University. He has written numerous works on political philosophy, history of philosophy, intellectual history and more. A Secular Age is Taylor’s attempt at putting a narrative to the transition that happens between, essentially, pre- and post-Enlightenment thinking and living. Specifically, Taylor wants to answer, narratively, “why as it virtually impossible not to believe in God in, say, 1500 in our Western society, while in 2000 many of us find this not only easy, but even inescapable?”1 This book fits, to a certain extent, within the same realm as John Milbank’s Theology and Social Theory or Catherine Pickstock’s After Writing, and other such intellectual histories that seek to describe how we arrived at our modern understandings of reality and society. Taylor’s book is massive and to help me engage more fully with it, I’ve decided to blog my way through it. I intend to take it a chapter at a time and so this first post will cover, to an extent, the Introduction and Chapter 1. However, I want to be clear, I am more giving my thoughts on this book as I work my way through it rather than reviewing or intentionally critiquing it. My plan is just to highlight what I found interesting or problematic about the book as I move through it, so take my opinions with a grain of salt. If you’ve read the book, feel free to correct me when I’m wrong. If you haven’t, feel free to take it up with me and comment as you read the sections on which I am commenting. Now, to the thing!

In the Introduction, Taylor is laying out what he intends to do in this book, specifically, to describe how we moved from a porous self in an enchanted cosmos to a buffered self in a secular age. I’ll tackle porous/enchanted and buffered in a moment, but first, I want to address Taylor’s understanding of secular. Taylor describes three different kinds of secularity but wants to focus on the third kind, “which [he] could perhaps encapsulate in this way: the change I want to define and trace is one which takes us from a society in which it was virtually impossible not to believe in God, to one in which faith, even for the staunchest believer, is one human possibility among others.”2 This third sense of “secular” is in essence where religious belief becomes one option among others and no longer the guiding principle by which life is lived. Taylor, however, does make it clear that religion is tied to all three kinds of secularity, ” as that which is retreating in public space (1), or as a type of belief and practice which is or is not in regression (2), and as a certain kind of belief or commitment whose conditions in this age are being examined (3).”3 This is interesting because Taylor is here arguing that secularity in general cannot cut its ties with religion, it cannot escape transcendence. It can only define itself in contradistinction from religion. Nevertheless, what Taylor wants to do is understand and narrate how we moved from what he will call the porous self to the buffered.

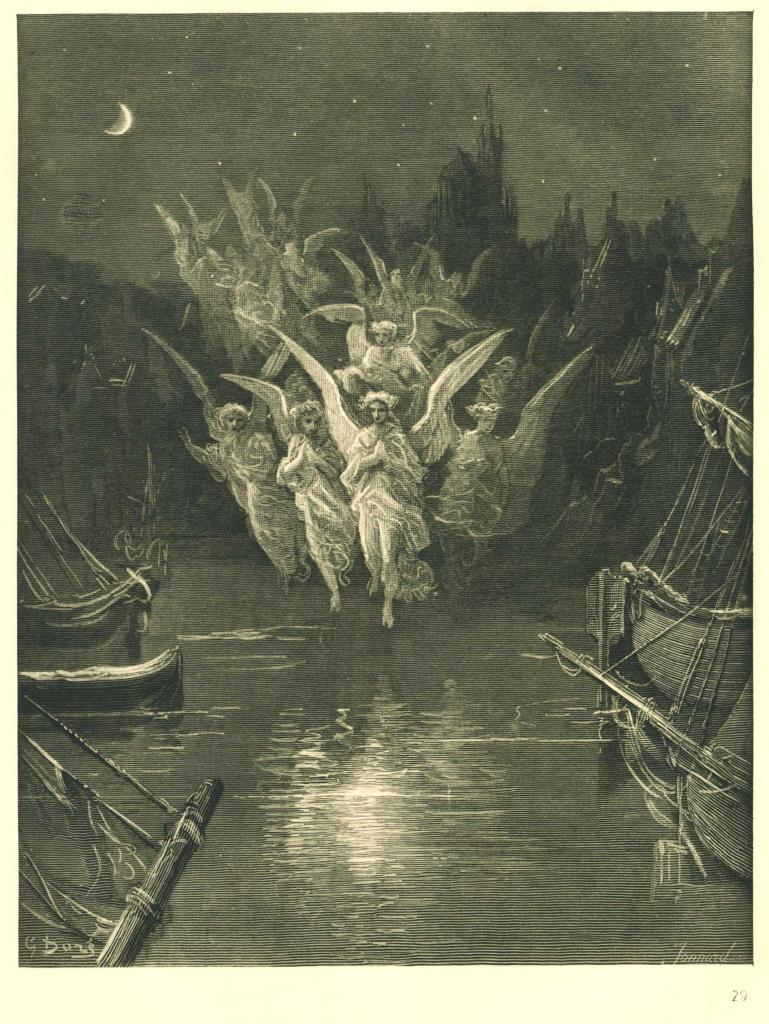

In Chapter 1, then, titled “The Bulwarks of Belief,” Taylor begins to define his terms, particularly porous/enchanted and buffered/disenchanted or secular. The enchanted world (which term Taylor takes up as the antonym to Weber’s disenchantment) is the world in which our pre-modern ancestors lived. For Taylor, “The enchanted world in this sense is the world of spirits, demons, and moral forces which our ancestors lived in.”4 I’m really quite intrigued by Taylor’s use of enchantment and his understanding of the premodern self. For readers of these letters, you’ll know I have an intense interest in enchantment (which I often equate with sacramental and liturgical). It seems to me that Taylor means something similar, however, he is far less interested than I am, for instance, in developing a theology of enchantment or premodern understanding. This is largely because Taylor is offering a narrative and not explicitly arguing for one position over another (or at least not yet).

Taylor understands the person living in the enchanted cosmos as porous, that is open to these spirits, demons, and moral forces not as two minds (or more) that can work together or against one another, but as porous, capable of being internally affected by them. For the porous self, meaning is not primarily in the mind as they are for the buffered self. Taylor describes the buffered understanding of meaning this way,

“On the former view meanings are “in the mind” in the sense that things only the meaning they do in that they awaken a certain response in us, and this has to do with our nature as creatures who are thus capable of such responses, which means creatures with feelings, with desires, aversions, i.e. beings endowed with minds, in the broader sense.”5

An object only has meaning insofar as I, as a being with intellect, imbue it with such. A tree is beautiful or menacing precisely because I feel it to be so, not because the tree itself has beauty or menace. But for our porous ancestors this was not the case. Meaning existed in things. Taylor describes this through the cult of the saints:

“But seeing things this way understates the strangeness of the enchanted world. Thus precisely in this cult of the saints, we can see how the forces here were not all agents, subjectivities, who could decide to confer a favour. But power also resided in things. For the curative actions of saints was often linked to centres where their relics resided; either some piece of their body (supposedly), or some object which had been connected with them in life, like (in the case of Christ) pieces of the true Cross, or the sweat-cloth which Saint Veronica had used to wipe his face, and which was on display on certain occasions in Rome. And we can add to this other objects which had been endowed with sacramental power, like the Host, or candles which had been blessed at Candlemas, and the like. These objects were loci of spiritual power; which is why they had to be treated with care, and if abused could wreak terrible damage.”6

Taylor gets more precise and notes that these meaningful (in the true sense of that word) objects relate on a cosmic level, “So in the pre-modern world, meanings are not only in minds, but can reside in things, or in various kinds of extra-human but intra-cosmic subjects. We can bring out the contrast with today in to dimensions, by looking at two kinds of peers that these things/subjects posses.”7 I am reminded here of John Milbank’s article “Fictioning Things” where writes that the objects in fairy-tales often function as the movers of the plot:

“Fairy-tale yields up a symmetrically opposite paradox: the circulation of objects in the basic plot is shadowed by the operations at a meta-narrative level of misty personages––senders and helpers, preternaturally “other” fairy figures and giants or else legendary human persons. Moreover, though the human heroes and heroines of the main plot are ciphers, who simply receive gifts as well as performing impossible tasks, etc. these ciphers, unlike the more strongly characterized gods or heroes, do in the end triumph, thanks to the mediations of the magical objects and a series of exchanges at the meta-narrative level with the “other” fairy realms.”8

What Milbank describes, it seems to me, is the same kind of relationship between the saint and the relic as described by Taylor. These meaningful objects filled with power and thus cause an affect whether one intends them to or not (one might think of Uzzah and the ark, the One Ring in The Lord of the Rings, or other similar examples). Taylor describes the good objects as capable of good or ill depending on how one uses them, though he never describes whether or not an object imbued with evil power could be used for good if used inappropriately. What Taylor is missing here, so far as I can see, is an extra level of connectivity. The relic of a saint is imbued with power from the saint, but the saint herself is imbued with power from God. Thus the grace mediated through a physical object ultimately receives its power from God. So while meaning is not simply in the mind, that is in the human or even angelic mind, it is ultimately founded in the mind of God. Why Taylor does not, in this chapter at least, make this point, I cannot say.

Another key to the porous self and the “charged” objects is that the effects of the charged object often function on multiple levels. When describing the healing that is given by such an object, Taylor notes that this healing is often not limited to the physical:

“That is, the same force that healed you could also make a better, or more holy person; and that in one act, so to speak. For the two disabilities were often seen as not really distinct. This shows that in, for instance, the healing at and by shrines, relics, sacred objects, etc., we are dealing with something different from modern medicine, even where the analogy seems closest.”9

Without being explicit, Taylor recalls two, almost contrary ideas. On the one hand, I, at least, am reminded of the healings effected by Jesus. Often is the physical healing accompanied by a forgiveness of sin. However, and here is where either Taylor himself, or, possibly, our premodern ancestors, could (or did) go wrong, which is to suggest that there is a direct connection between the physical ailment and particular unholiness. Christ himself denounces this when asked by his disciples who sinned in the case of the man born blind. However, it is clear that there is a connection (from Genesis 3 onward) between our physical ailments (that we die) and our sinfulness.

Taylor’s description of the enchanted cosmos is one that is inherently social. “But living in the enchanted, porous world of our ancestors was inherently living socially. It was not just that the spiritual forces which impinged on me often emanated from people around me, e.g., the spell cast by my enemy, or the protection afforded by a candle which has been blessed in the parish church. Much more fundamental, these forces often impinged on us as a society, and were defended against by us as a society.”10

The buffered self, it would seem, though Taylor has not made this argument explicit as of yet, is one that not only puts up boundaries between me and creation (whether spiritual or physical) but also between me and other selves. If the porous self is inherently social, the buffered self is inherently individual.

Taylor is clearly not, at present, arguing for a return to the porous or enchanted. I’m not sure he believes this possible. Problematic for me is that Taylor does not seem even to be interested to ask whether or not it is true. I understand that his purpose is to narrate, to describe, and he is doing that. So I cannot fault him for doing what he set out to do; I just wish he were doing something a little different, but that’s my problem, not his.

Well thanks for enduring this long post, if you have. If you’ve read this book, let me know if I’m wrong (or right) and what I might have missed.

Sincerely,

David

1 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007), 25.

2 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007), 3.

3 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007), 15.

4 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007), 26.

5 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007), 31.

6 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007), 32.

7 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007), 33.

8 John Milbank, ‘Fictioning Things: Gift and Narrative,’ Religion and Literature, 37:3 (Autumn 2005): 15.

9 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007), 39.

10 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007), 42.