David Russell Mosley

Author Heikenwaelder Hugo, Austria, Email : [email protected], www.heikenwaelder.at, CC BY-SA 2.5

Ordinary Time

3rd Sunday after Trinity

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Readers,

Richard Beck, Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychology at Abilene Christian University, and author of several books keeps a website he calls Experimental Theology. Richard is, like myself, from the Restoration or Stone-Campbell Movement. Therefore, when a friend shared with me one of Beck’s posts on Sacramental Ontology, I was quite excited. Another Protestant talking about Sacramental Ontology, and one of my own, current, variety? I couldn’t believe it. Then, however, I read the post and the one preceding it. Beck has since written several more posts on what he calls “Edging back to Enchantment” (it’s as though he had me in mind when he wrote these titles) that are also of interest, but I want to focus on the first two, “The World Is Charged With the Grandeur of God” and “A Sacramental Ontology.”

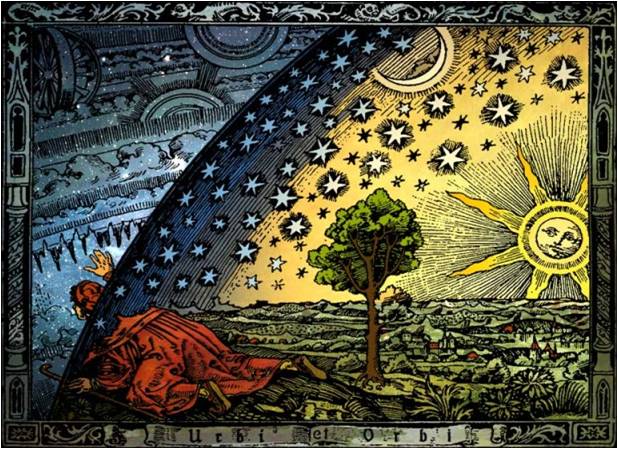

In the first post, Beck wants us to consider the return to a vision of creation as filled with God’s presence. The way we are to do this is by embracing God’s immanence. Beck claims that emphasizing God’s transcendence leads us only to see God as being outside of creation, detached from it. He argues that, “Transcendence also tends toward deism, furthering our disenchantment.” There is a problem, however. God’s transcendence and immanence are not diametrically opposed. Rather, it is precisely because God is transcendent (not consonant with creation) that God can be immanent. Consider Aquinas’ Five Ways (ST Ia. 2, 3). For Aquinas, God is the First, and Unmoved Mover; the First, and Uncaused, Cause; the Necessary, and Source of, Being; the Source of not only all things being, but their goodness, and perfection; and the Final Cause. When we look at these different Ways we see that they ensure the difference between God and creation. Unlike creation, God is not moved or caused; he is transcendent. Unlike creation, God is his own source of being, nothing brought him into existence. So, God is transcendent. Yet, God is also the First Mover, the First Cause; he shares with creation his being, his perfection, and he directs creation toward its final end, namely himself. He is immanent. Yet this, we see from Aquinas, means that God must be transcendent in order to be immanent. He must be other from creation in order to be close to creation, even closer to creation than creation is to itself. Beck, therefore, appears to be missing this crucial understanding, that transcendence and immanence are not opposed to one another, rather one upholds the other.

In his second post, Beck now wants to enter into a discussion of Sacramental Ontology. He pulls exclusively from Hans Boersma’s Heavenly Participation (as well as a few references to Scripture). Beck, from Boersma, rightly understands that a sacramental ontology is a participatory ontology (that is, that all things, by nature of their existence––remember, God is the source of our being as Aquinas says above––participate in God) and that this implies that God is “miraculously” involved in creation (I hope to write another letter on miracles some day). However, Beck, again, begins to go slightly wrong. He writes at one point:

In a sacramental ontology there is an overlap between God and creation–an intermingling of the earthly and the heavenly, the human and the divine, the mundane and the holy, the secular and the sacred, the natural and supernatural, the material and the spiritual.

The problem with this is largely a lack of nuance. Beck is not wrong that when we are dealing with sacraments and sacramentals we are talking about an overlap between heaven and earth. Yet this notion of overlap almost suggests the opposite of what Beck is trying to say. If there are only some places where the divine and earthly realms overlap then there are places where they do not. I, of course, agree that there are holy places and things, things that are more holy than others. However, if God is truly immanent to his creation then while somethings can be holier than others, all things, insofar as they exist still participate in God and are, to that extent, holy. This becomes even more problematic when Beck “tweaks” an image shared by Boersma in his book. In Boersma’s book the image is depicting the kind of overlap or lack thereof that takes place when a thing is merely a symbol (lack of overlap) and when a thing is a sacrament (overlap). Beck uses this to depict the difference between transcendence (lack of overlap) and immanence (overlap). I’m almost certain Boersma (and am certain that Boersma’s sources, the ressourcement theologians) would balk at such a claim.

As I’ve said, Beck has written several more posts in this series––dealing with sacramentals and the Catholic imagination––and these have some merit and value, as do the posts on which I have commented. Nevertheless, it seems to me that Beck would benefit from digging more into the sources and not simply Balthasar, Lubac, Congar, Daniélou, et al.; but also to read Dante, Aquinas, Maximus, Denys the Areopagite, Augustine, the Cappadocians, Athanasius, and more. If we’re going to embrace enchantment (and I think we should), if we’re going to embrace a sacramental/participatory ontology (and again, I think we should) then we need to understand the terminology, we need to go back to the sources. It isn’t enough to latch onto a beautiful phrase and work from there. More importantly, insofar as Beck is concerned, we need to remember that if we want to emphasize God’s immanence we cannot evacuate his transcendence. Precisely because God is not creation can God be so intimately close to creation.

Sincerely,

David