David Russell Mosley

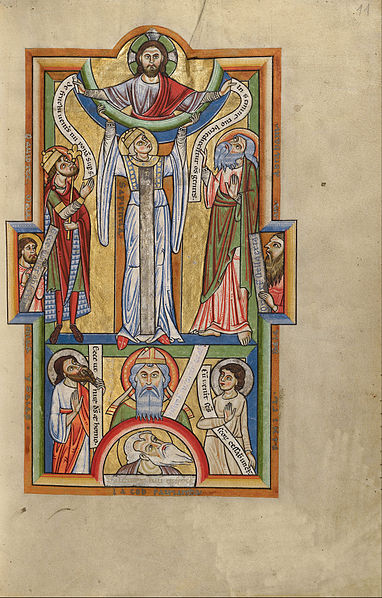

Artist Unknown – illuminator

Title Wisdom

Object type Folio

Date probably 1170s

(Public Domain)

Ordinary Time

St. Matthew

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Readers,

Yesterday, I wrote to you about food, quoting somewhat from Angel F. Méndez-Montoya’s excellent book, The Theology of Food: Eating and the Eucharist. Today I want to interact a bit more with his section on Sophia and food.

In Proverbs 9.1-6, Wisdom, who is depicted as a woman (and I simply refuse to believe that this is merely because the word is feminine in Hebrew––as well as in Greek and Latin and likely other languages as well), has prepared a palace for her abode and a feast for her lovers. Here is the passage in full:

Wisdom has built her house,

she has hewn her seven pillars.

She has slaughtered her animals, she has mixed her wine,

she has also set her table.

She has sent out her servant-girls, she calls

from the highest places in the town,

‘You that are simple, turn in here!’

To those without sense she says,

‘Come, eat of my bread

and drink of the wine I have mixed.

Lay aside immaturity, and live,

and walk in the way of insight.’

Méndez, whose Sophiology, it would seem comes almost entirely from Bulgakov’s Philosophy of Economy: The World as Household, comments on this passage as related by Bulgakov writes:

“Bulgakov echoes Proverbs 9:1-6, where Sophia shares a banquet, and alludes to her metaphorical identification with meat, bread, and wine. Food points to the root of being as ultimately relational – the very character of Sophia. Sophia is, for Bulgakov, the true expression of the metaphysical, social, and economic life. A similar analogy could be drawn with regard to food. At the metaphysical level, being is the food/substance offered as a gift from God, and thus intimately related to or participatory in the divine.”1

Sophia is the divine sharing of God-self to his creatures. This happens now, if not exclusively, primarily through the food of the Eucharist, bread and wine, which have prominent place at Sophia’s feast in Proverbs 9. Méndez further highlights this when he writes:

“Sophia is God’s own sharing that gifts creation with a food and drink that is God-self, God’s love: “God’s love for what he creates implies that the creation is generated within a harmonious order intrinsic to God’s own being” (Theology and Social Theory, 429). God offered as food and drink is further radicalized in the eucharistic sharing where the elements of bread and wine become a source of that same divine-sophianic sharing. This is the most physical and material aspect of deification. Therefore, rather than merely constructing an ontology intrinsically intensifies the materiality, corporeality, and contingency of Being, and displays a complex, metaxological – to use Desmond’s account – realm. For divinity reaches beyond humanity, into the realms of the material (bread and wine), only to reconstitute the mystery of materiality as eucharistic: an expression of thanksgiving, that is, a reception and return of God’s gift.”2

Méndez’s use of Sophia here is that of bridge. She bridges the divide between Creator and creature that was first, or perhaps simultaneously, bridged by Christ. This makes me think of the two kinds of participation one can find in the writings of Thomas Aquinas. For Aquinas, all existent things participate in God since God is the source of all being. Therefore created things (everything that isn’t God) participate in God’s being since, in a sense, God is the only existent being and he shares his existence with his creatures. This extends to all created reality, from the lowest, basest form of matter (and the microscopic and atomic realities that make it up) to the highest of the Seraphim. However, humans in general and Christians in particular have a special share in God. Because humanity has been united to divinity in a new way in the Incarnation, humanity now has a special share in God’s divinity. Sophia, then, in many ways symbolizes both of these realities. Before Christ she was still the Wisdom of God toward which all things are ordered (as the divine nature); after Christ, it is still God’s Divine Wisdom that, as Méndez says, “reaches beyond humanity, into the realms of the material (bread and wine).” Thus it is not so much, or not even primarily, Wisdom that we meet at Wisdom’s banquet but Christ, made present in the bread and wine by the transformative power of the Holy Spirit at the invocation of God the Father. Thus, as the whole Trinity is present in this moment, Sophia is present in this moment.

Sophia remains an enigmatic figure for me. She is not, quite clearly, a fourth hypostasis. The Trinity is not, in reality, a Quadrinity. And yet it is not, it would seem, totally wrong to think of her as a person, to assign pronouns to her. I did not go looking for her when I read Méndez’s book. In fact, the book was recommended to me by a friend who is very skeptical of Sophiology in general. And yet, as I read this excellent book, there she was. Whatever we may think of the “person” of Sophia, there is no denying the reality of God’s Wisdom. There is no denying the inherent relationship between Wisdom and the Son as well as Wisdom and the Spirit, thus solidifying that God is Wisdom. There is no denying that when we come to the Eucharist that table-altar it is just as much the banquet of Wisdom that we are attending as it is the Wedding Feast of the Lamb. There is, therefore, also no denying the change in our relationship to food because of this feast. Rather than see eating as related to cycles of death, Méndez encourages us to see food as participating in cycles of ultimate Life:

“An alternative Catholic reading of eating affirms that, through eating in the Eucharist, unity with God is restored, and a promise of resurrected life is opened up. From this eucharistic perspective eating is not a condition of lack, but a foretaste of divine plenitude: a physical and spiritual tasting that kindles a desire for more, for that beautiful excess wherein there is yet more to savor.”3

“From these sophianic and eucharistic perspectives, food is not severance, nor does it bring about ultimate destruction and final death. Instead, what Sophia and the Eucharist convey is food as a material – as much as it is also a divine – sign of relationality, interdependence, and sharing of life eternal.”4

When we meet Christ at the table we meet Life Himself. We meet the one who is vita ex morte, Life from death. This is our hope.

Sincerely,

David

1 Angel F.Mendez-Montoya, The Theology of Food: Eating and the Eucharist (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 89.

2 Angel F.Mendez-Montoya, The Theology of Food: Eating and the Eucharist (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 111.

3 Angel F.Mendez-Montoya, The Theology of Food: Eating and the Eucharist (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 109.

4 Angel F.Mendez-Montoya, The Theology of Food: Eating and the Eucharist (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 114.