David Russell Mosley

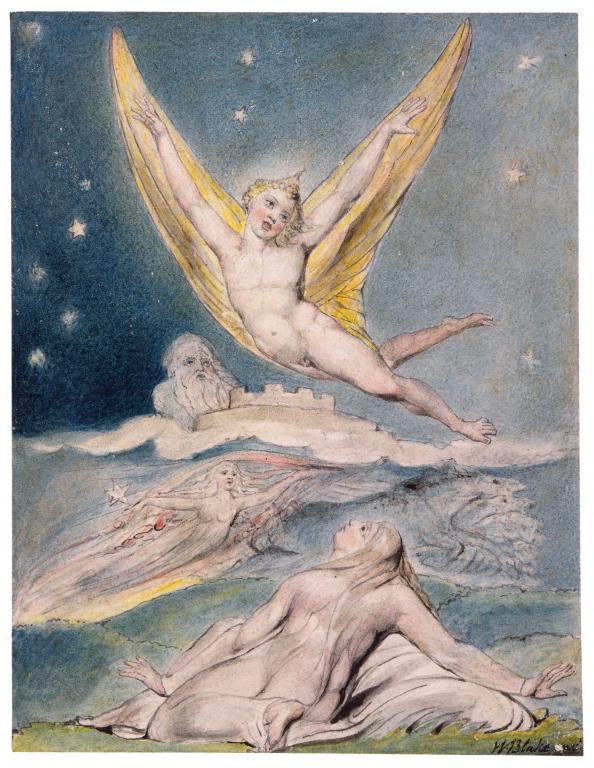

English: Front view of the “Angel of Death Victorious” statue created by Herman Matzen for the Francis Haserot grave site located at the Lakeview Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio.

Date 27 October 2012, 16:44:13

Source Own work

Author Ian MacQueen

(CC BY-SA 3.0)

Ordinary Time

9 February 2017

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Readers,

I’ve been thinking about life lately. Particularly, I’ve been thinking about what it means to be pro-life and to be open to life. What does it mean to be pro-life? And what is it’s opposite? Is it pro-choice or pro-death? I actually remember reading somewhere on social media (Facebook I think) someone saying that no one is actually pro-death. We’re all pro-life. And I wondered is that true? Is our culture (and while I particularly mean American culture, I mean Western, even global capitalist, and socialist culture(s) in general) actually a culture of life? I’m not so sure. I think we may actually be a culture of death, a necrophiliac culture. Let me attempt to explain.

In her first book, Catherine Pickstock suggests that modernity is inherently necrophilic. She suggests that our attempts to prolong life by whatever means possible into a kind of “pseudo-eternity” is actually necrophilic. She writes:

“Such pseudo-eternity is composed of things which are only preservable and manageable as finite, and therefore as “dead.” On this basis it can be claimed that modernity less seeks to banish death, than to prise death and life apart in order to preserve life immune from death in pure sterility. For in seeking only life, in the form of a pseudo-eternal permanence, the “modern” gesture is secretly doomed to necrophilia, love of what has to die, can only die. In seeking only life, modernity gives life over to death, removing all traces of death only to find that life has vanished with it” (104).

Later she writes:

“So, to posit death as opposite and unnatural to life, is to incite us to attempt to prolong our lives by certain sacrificial investments. This is of course not exclusive to capitalism [she has previously argued that the drive for security is an attempt to divorce death from life], for state socialism also aimed at the exorcism of death through the being of class and the scheme of eternal accumulation of productive forces. In both cases, the sanctification of labor is predicated on human life as a positive value, which requires a denigration of, and therefore a sacrifice to, death” (105).

Pickstock’s point is that these attempts to divorce death from life, to make life as it is now the ultimate good, are ultimately necrophilic, they are a love of death, a sacrifice to death of life.

This got me thinking about C.S. Lewis’ prescient work, That Hideous Strength.