David Russell Mosley

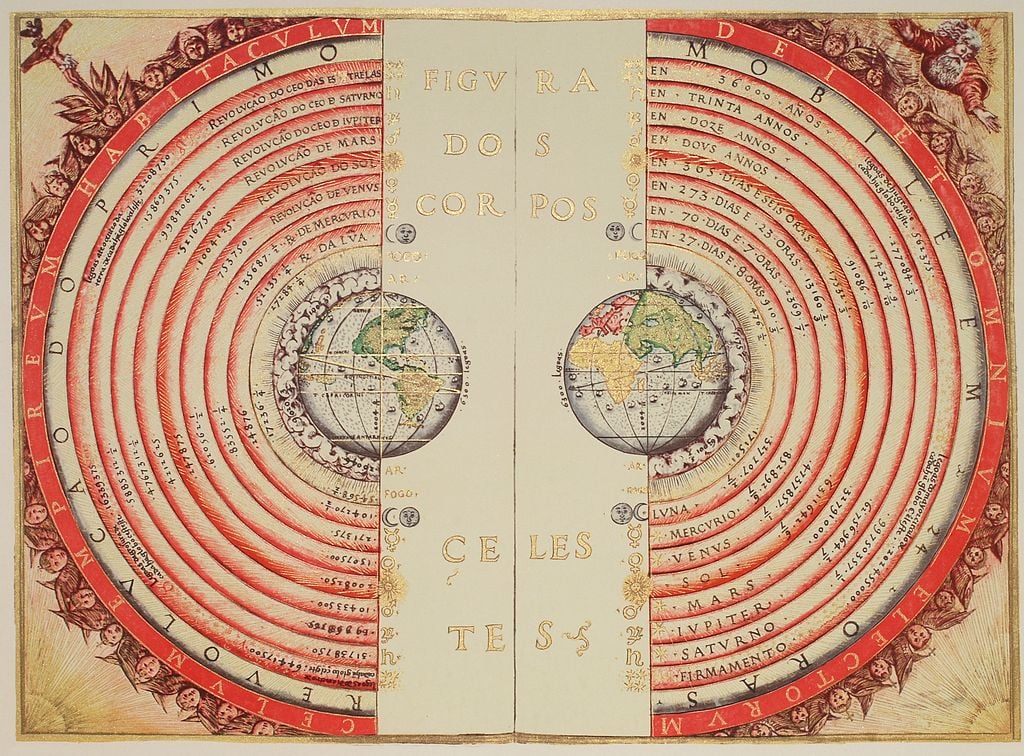

English: Figure of the heavenly bodies – Illuminated illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric conception of the Universe by Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velho (?-1568). From his work Cosmographia, made in France, 1568 (Bibilotèque nationale de France, Paris). Notice the distances of the bodies to the centre of the Earth (left) and the times of revolution, in years (right). The outermost text says: “The heavenly empire, the dwelling of God and of all of the elect”

Date Original work, 1568. Photo taken in 2008

Source Own work

Author Bartolomeu Velho

Eastertide

9 June 2017

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Readers,

Two nights ago, after a long and hard day, I sat outside with my pipe and my computer under the stars. I’ve been slowly doing some work on Medieval cosmology, which will hopefully pick up if my paper proposal is accepted. Because of this, my night under the stars took on a different flare. Lewis in The Discarded Image recommends that one must take starlit walks in order to truly get inside the mind of our medieval ancestors. He writes:

“You must go out on a starry night and walk about for half an hour trying to see the sky in terms of the old cosmology. Remember that you now have an absolute Up and Down” (DI 98).

Later he writes:

“You must conceive yourself looking up at a world lighted, warmed, and resonant with music” (DI 112).

How different from our modern conceptions of space!

So I sat there, listening to the music of crickets, frogs, and whistlepigs. Suddenly I looked over my shoulder and saw someone looking at me. At first I thought it was Venus. She had been a constant companion in the evenings of the Winter. But a quick check of star charts showed me I was wrong. It was not Venus, but Jove himself, the king. I laughed when I realized my mistake. Luna too was present and nearby. She was full and shone bright. I tried to get pictures of them both, but to little avail.

Then, yesterday, I sat down to read some more Boethius. As I was reading in Book IV, I came across this poem from Lady Philosophy:

‘For I have swift and speedy wings

With which to mount the lofty skies,

And when the mind has put them on

The earth below it will despise:

It mounts the air sublunary

And far behind the clouds it leaves;

It passes through the sphere of fire

Which from the ether heat receives,

Until it rises to the stars,

Where Phoebus there to join its ways,

Or said with cold and ancient Saturn

As soldier of his shining rays.

Wherever night is spangled bright

The orbit of a star it takes,

And when the orbit’s path is done

The outmost pole of heaven forsakes.

It treads beneath the speeding ether

Possessing now the holy light,

For here the King of kings holds sway,

The reins of all things holding tight,

Unmoving moves the chariot fast,

The lord of all things shining bright.

If there the pathway brings you back –

The path you lost and seek anew –

Then, “I remember,” you will say,

“My home, my source, my ending too.”

And if you choose to seek again

The lightless earth which you have left,

Dictators whom the people fear,

Will outcasts seem of home bereft.’

I could perhaps spend many letters unpacking this poem. But for now, I want to focus on one aspect in particular. The poem concerns the soul’s ascent to God. First in passes through the sublunary spheres (that is, everything below the moon) and then passes through the heavenly spheres. Of course, we must remember that for Boethius, everything beyond the moon was perfect, in capable of corruption, though capable of movement. But once you get beyond the spheres, you reach what Dante calls the Empyrion, the final sphere, which is the mind of God. Here, we discover, implicitly in Boethius and explicitly in Dante, that the cosmos is inverted. From our sublunary perspective, it appears that the Earth is the center of things (which, of course, is actually very bad for us since it also means we’re the bottom and capable of corruption). However, as the soul ascends to God we realize, that God is the source of light and thus the true center of the cosmos. It is a kind of exitus and reditus. We exit out from earth and reach God only to discover that rather than having left the center of the universe, we have come into it. As the universe is inverted, and we see the Earth as the lightless planet furthest from the center, we take that light back with us.

Lady Philosophy is helping Boethius understand why it appears that the wicked have so much power and do so well on Earth. It is because our perspective is off. Dictators and other wicked, but seemingly powerful men, do not belong here. Or more, they do, insofar as the Earth stands as that place furthest from God, because they do not recognize that their true home resides in God. It is a matter of perspective, that once righted (by ascending to God and returning to Earth) shines a new light on all that we experience in the sublunary sphere.

And so, I look forward to more nights with Jove looking over my shoulder. He shines brightly to remind me that the true center of the cosmos is the mind of God which both contains all the created spheres as if it were the largest sphere of all and yet is the center from which all the spheres spin out. In the end, the medieval cosmos, and our own, is theocentric.

Sincerely,

David