Author Heikenwaelder Hugo, Austria, Email : [email protected], www.heikenwaelder.at, CC BY-SA 2.5

Advent

St. Lucy’s Day 2018

The Edge of Elfland

Concord, NH

Dearest Readers,

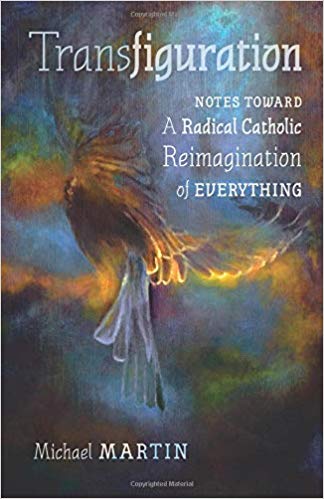

Now that it has been officially released, I would like to tell everyone about Michael Martin’s most recent book, Transfiguration: Notes Toward A Radical Catholic Reimagination of Everything. This book is Martin’s manifesto, his declaration of how we ought to see and interact with the world around us. It is not, however, a program. Martin isn’t here to tell us all the ins and outs of how we ought to put the radical Catholic reimagination of everything into practice. Rather, he wants to draw our attention to better ways of knowing, of seeing the world around us.

Now that it has been officially released, I would like to tell everyone about Michael Martin’s most recent book, Transfiguration: Notes Toward A Radical Catholic Reimagination of Everything. This book is Martin’s manifesto, his declaration of how we ought to see and interact with the world around us. It is not, however, a program. Martin isn’t here to tell us all the ins and outs of how we ought to put the radical Catholic reimagination of everything into practice. Rather, he wants to draw our attention to better ways of knowing, of seeing the world around us.

Martin even says in his introduction, “I do not expect that the ideas in this book will be taken up by my contemporaries. That may seem a maudlin confession, but the sense of vocation out of which this book was written did not come with a promise of reward. My only hope is to leave an artifact, a broken shard of pottery from a vessel that once held wine. It no longer belongs to me.”

There many things I could focus on as reviewer. But I would rather keep this review short and not reveal too much so that you will desire to read the book for yourself. So first, I would like to discuss two points of contention. In the second chapter, “Art as Eschatology,” Martin discusses the need for art to look forward rather than back. In one swipe he takes a swing at Great Books Programs and Lewis, Tolkien, and O’Connor. I will leave O’Connor to be considered by those who know her better. I will also leave the Greek Books to my next section on education in Martin’s book. Rather, my focus is on Lewis and Tolkien.

Martin writes, “This is even the case with the all-too-habitual invocations of inhabitants of a more recent past—C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, or Flannery O’Connor—and whose acolytes often see fit to adopt the requisite uniforms of beards, pipes, tweeds, if not crutches and peacocks. These tombs are beautiful, brothers and sisters, but they are still tombs” (37). I understand what Martin means. Devotees of Lewis and Tolkien can be a peculiar bunch, thinking that the height of art or life was to be found in the 1940s and 50s. This is, of course, untrue. Of course, I also take this a bit personally since I do have a proclivity for tweed and pipe tobacco. Nevertheless, I think Martin too dismissive here as much of what he goes on to write about I have found and learned to love first through the works of both Lewis and Tolkien. Even if one tried to claim that much of their work is a look back, it is so only in order to then look forward.

My next point of contention comes from the third chapter, “The Reimagination fo Education and the Postmodern Sophiological Hedge School.” Here Martin takes to task not only the Great Books programs that have been growing for the last 60 or so years but also the rise of Catholic Classical schools. He points instead to the hedge schools of occupied Ireland, where Catholics taught children in secret. Here I am even more understanding of Martin’s point. Accreditation, standardized testing, and mimicry of secular models of learning have led many Catholic schools astray. Still, I find his characterization does not fully fit the very school in which I currently work. Here again, of course, I could just be personally biased, but I think things may be more hopeful, or be better prepared for the kind of education he envisions, than he allows.

These two points of contention aside, I cannot recommend this book enough. In such a short space, Martin has clearly and beautifully expressed better ways of knowing and understanding reality. All of this, as should be expected for readers of Martin, comes through a sophianic lens. Science, for instance, ought to be undertaken in and as a relationship between the knower and the things to be known. Martin holds Goethe, David Bohm, and Rupert Sheldrake as scientists not of the laboratory but of creation, of the cosmos. And it is this, the cosmological that ties together the entire book.

Martin is calling us to an integrated way of being, one which allows the cosmos, the seasons, the liturgical calendar, our art, our education all to be related and mutually informing of and to one another. Martin writes:

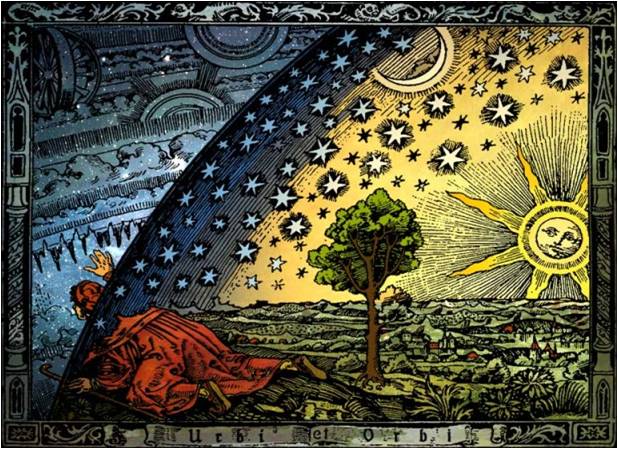

“Cosmological awareness” is a fancy way to say that we need to attend to and interiorize the rhythms of nature and their relationship to the Church year. This would have different applications in the southern hemisphere than in the northern, of course, but, wherever one lives, it should not be all that difficult to connect the two.

I am reminded not only of Louis Bouyer, but of Dante and Tolkien and Lewis, here. The claim we ought to be making as Catholics is that the liturgical calendar is disclosive of reality, not simply in some ethereal, spiritual sense, but in a real, phenomenological sense. Christmas being celebrated on December 25th, whether in conjunction with the Winter Solstice or the Summer (depending on one’s hemisphere) is on purpose and not simply an accident of history. What is more, December 25th has a name, not a date, and this should change how we encounter it.

Wholistic, were it not such a buzzword, is precisely the word I think most would understand as the key to Martin’s Transfiguration. He, of course, would prefer such words as sophianic, sophiological, or even cosmic/cosmological. And he would be right. Still, his emphasis is on the whole, an integrated whole where everything in creation touches everything else. And thus our science, our art, and our education ought to serve as aids and examples of this reality. Whatever issues I may take with aspects of Martin’s approach, his emphasis on the whole is, in my opinion, precisely the right one and precisely the one we need now more than almost anything else.

So take up this book and read. Prove Martin wrong that his contemporaries will not act on his words. By all means challenge him, but do not ignore him. We do so, I fear, to our peril.

Sincerely,

David