Ordinary Time

25 February 2019

The Edge of Elfland

Concord, New Hampshire

Dearest Readers,

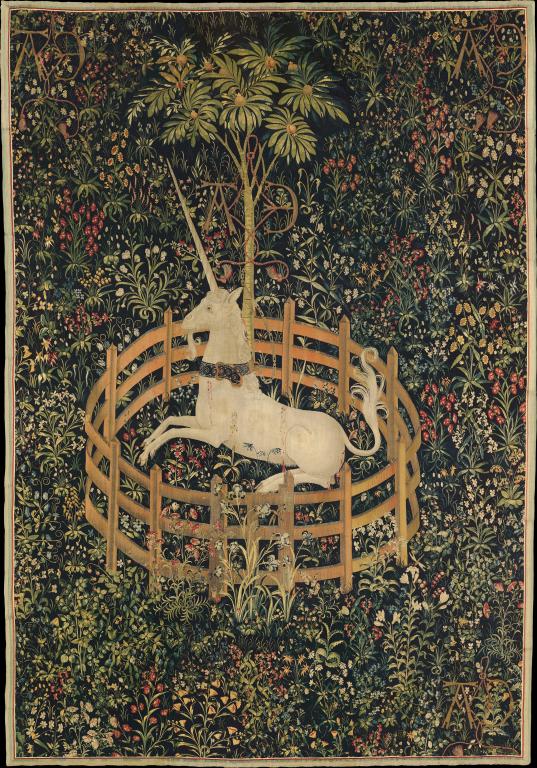

Recently I came across a Ranker “article” concerning the real unicorn. The article (CNN actually has one just like it) was concerned with two issues: first, to disabuse modern readers of misconceptions concerning unicorns, primarily their existence or non-existence; second, to show readers the “real unicorn,” a creature whose bones we have found and who, according to the articles, is the source of all our modern stories about unicorns. This reminded me of similar articles concerning Neanderthals. These argued that perhaps Neanderthals stand at the back of our stories about elves, trolls, ogres, etc.

A younger me might have found these arguments convincing. As a child I was particularly obsessed with bigfoot. I would plot sightings of it I discovered on the internet on a giant map of the world I had in my bedroom. I loved this idea of a creature that spanned man and our more irrational ancestors. And so these articles would have been of interest. I would have been able to say, “See! They were real, just not in the way we thought.” I would have basked in the possibility of these fantastical creatures existing even along such modernistic lines. Now, however, I see them as containing two chief errors.

The first error is that of demythology. This is a trend one sees especially in biblical studies. It typically starts with the presupposition that something which appears miraculous must have a purely natural explanation (and by purely natural they mean to bracket out anything “supernatural”). Thus these events, if they really happened, are in need of a more realistic explanation. Thus, when Christ feeds the five thousand, there was not a miraculous multiplication of food, but a miraculous act of sharing on the parts of those who did bring food with them as a response to Christ’s message. Of course, this doesn’t explain why the people kept following him looking for food, but I digress.

So, take the “real unicorn” or Elasmotherium sibiricu. It was a creature that existed as early as 29000 years ago, when humans were roaming the earth. The story essentially goes like this then. These early humans saw the Siberian unicorn, probably killed and ate it, but also told stories about it. These stories get passed on, but like in a game of telephone they get distorted in the retellings. Eventually, this large rhinoceros type creature gets remembered as a stately goat-like creature or as an even statelier horse who prefers the company of virgins. You can see the demythology at work. We have stories about unicorns. Unicorns, as described in these stories, cannot exist. Therefore, this more naturalistic explanation is the real story. This works for the Neanderthals are elves/trolls/ogres demythology. These fay-creatures cannot exist, so we must find a more natural explanation. Neanderthals were weird looking and unusual compared to their homosapiens cousins and so gave rise to the stories we’ve told ourselves about creatures like us but also vastly different from us.

The second error I think these authors have engaged in, which is tied to their demythology, is the desire to find an origin for these stories. J.R.R. Tolkien writes in his essay, “On Fairy-stories,” “To ask what is the origin of stories (however qualified) is to ask what is the origin of language and of mind.” For Tolkien, story, myth, and language all arise as one. This is why, when he started inventing his own languages now found in his Legendarium, he wrote his Legendarium. It was not enough, for him, to say that the Sindarin word for tree is galadh is not enough for Tolkien. Not only does he want to understand how it arrived at its present form, but how it has been used, what stories are involved with it. Tolkien admits that there is, good, interest in unraveling, “the intricately knotted and ramified history of the branches on the Tree of Tales,” but he goes on to say, “that it is more interesting, and also in its way more difficult to consider what they are, what they have become for us, and what values the long alchemic processes of time have produced in them.”

Thus when these articles suggest that Elasmotherium sibiricu is the real unicorn or that Neanderthals are the real trolls they have, in a sense, done some violence to our stories about unicorns and trolls. Now, the origin of our stories of trolls and unicorns is still important, or at least of interest. But looking only at the biological or archaeological will not give us the answers. This is not because Elasmotherium sibiricu isn’t the one of the sources for our stories about unicorns. It is entirely possible that it played a role. But to say that it is the real unicorn is to act as though our stories about unicorns are simply a distorted picture of reality. It is, in short, to ignore the actual story. By all means do your detective work, but remember that etymology plays an even more significant role here that biology or archaeology. Remember that the stories themselves have life and that they call on us to attend to them, to the stories as a whole, not just to the parts.

Sincerely,

David Russell Mosley