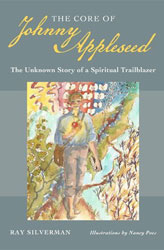

One of my family’s cherished, non-negotiable traditions, ranking right up there with summer camping trips and New Year’s Eve fondue, is an October drive to western Connecticut, where we pick apples, sip hot cider, and eat fresh-from-the-oven cider donuts on a hilltop farm that has been in the same family since the 1780s. Apples are central to autumn in Connecticut, not only in our household (where we eat some form of cooked apple—sauce, pie, crisp—nearly daily until all the apples run out some time in early December) but even in the school curriculum, which is where my kids first learned about Johnny Appleseed (whose real name was John Chapman). And up until now, when they came home with their interest piqued to ask me more about this legendary figure in early America (Why did he plant apple trees? Do we pick apples from his trees?), I didn’t know enough to answer. Thanks to Ray Silverman’s short and sweet new spiritual biography of John Chapman, The Core of Johnny Appleseed: The Unknown Story of a Spiritual Trailblazer, I now know enough about this fascinating character not only to answer my children’s questions, but also to inform and enrich my Christian life.

One of my family’s cherished, non-negotiable traditions, ranking right up there with summer camping trips and New Year’s Eve fondue, is an October drive to western Connecticut, where we pick apples, sip hot cider, and eat fresh-from-the-oven cider donuts on a hilltop farm that has been in the same family since the 1780s. Apples are central to autumn in Connecticut, not only in our household (where we eat some form of cooked apple—sauce, pie, crisp—nearly daily until all the apples run out some time in early December) but even in the school curriculum, which is where my kids first learned about Johnny Appleseed (whose real name was John Chapman). And up until now, when they came home with their interest piqued to ask me more about this legendary figure in early America (Why did he plant apple trees? Do we pick apples from his trees?), I didn’t know enough to answer. Thanks to Ray Silverman’s short and sweet new spiritual biography of John Chapman, The Core of Johnny Appleseed: The Unknown Story of a Spiritual Trailblazer, I now know enough about this fascinating character not only to answer my children’s questions, but also to inform and enrich my Christian life.

Silverman helpfully teases out the probable facts of John Chapman’s life from fiction. While Chapman had a respect and care for nature as God’s creation, he most likely did not go to great lengths to save mosquitoes from unwittingly roasting themselves by flying too close to his campfires, nor was he a pantheist who believed God lived in trees, insects, and rocks. While he likely went barefoot for much of the year (shoes were much less common and much more uncomfortable than they are today), he probably didn’t melt ice with his bare feet. Silverman also outlines the basic story that most of us are familiar with, how Chapman planted thousands of apple trees in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana as a way to preserve apple species and help farmers on the American frontier feed themselves, their families, and their communities.

Chapman’s Christian faith is a lesser known part of his story, but Silverman makes a convincing argument that it was central to who Johnny Appleseed was and what he did with his life. Chapman became inspired by the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish theologian and mystic. The author skirts around Swedenborg’s more controversial and odd teachings, such as his stories of visiting heaven and hell to converse with angels and demons, and it’s not clear what John Chapman thought about this side of Swedenborg’s theology. What is clear is that Chapman embraced Swedenborg’s emphasis on God’s love and goodness, which contrasted sharply with contemporary portrayals of an angry God intent on punishing sinful people. Chapman saw Swedenborg’s theology as “good news, right fresh from heaven,” and set about spreading this good news along with his apple tree seedlings.

When Chapman visited settlers to talk about planting apple tree nurseries, he often left behind chapters of Swedenborg’s books, returning later to swap old chapters for new ones. He explored the idea of giving away some of the land he owned in exchange for more copies of those books, so he could spread the good news more widely and efficiently. As Silverman explains, “[Chapman] played a vital role in providing seedlings for the early settlers who needed apple trees to survive, and thrive, on the physical frontier; but that was not his primary goal. His deeper mission was to share with them the life-giving truths that he found in Swedenborg’s writings—truths that would help them survive, and thrive, on the spiritual frontier.”

When Chapman visited settlers to talk about planting apple tree nurseries, he often left behind chapters of Swedenborg’s books, returning later to swap old chapters for new ones. He explored the idea of giving away some of the land he owned in exchange for more copies of those books, so he could spread the good news more widely and efficiently. As Silverman explains, “[Chapman] played a vital role in providing seedlings for the early settlers who needed apple trees to survive, and thrive, on the physical frontier; but that was not his primary goal. His deeper mission was to share with them the life-giving truths that he found in Swedenborg’s writings—truths that would help them survive, and thrive, on the spiritual frontier.”

For us modern folk who normally get our apples either from the supermarket or from apple trees on someone else’s land, what might we learn from Johnny Appleseed’s dual mission to spread God’s “good news, fresh from heaven” while teaching early Americans to survive and thrive on their new land with the help of the humble and hearty apple? For me, the Johnny Appleseed story is a wonderful example of what it looks like to embrace a God-given vocation. We so often associate the word “vocation” with work that is overtly religious, with the call to become ordained or take up some other kind of work that is clearly and obviously related to God’s mission. But John Chapman’s primary work was not obviously religious or theological. It was simple, physical, straightforward—to carry seeds and seedlings to those who could use them, to ensure that families and communities would have a useful, stalwart crop with which to feed themselves. That work, in and of itself, was rooted in Chapman’s faith—nature as God’s handiwork and gift, the planting of apple trees as symbolic of how God’s love is planted in us and bears fruit. When Chapman became inspired by Swedenborg’s writings, he looked for ways to spread his newly discovered faith along with his apple trees, instead of abandoning one work to take up another.

Isn’t this the place that most of us find ourselves? Most of us aren’t called to become preachers or missionaries or theologians, but rather teachers and librarians and doctors and writers and plumbers and farmers and parents and office managers. If we are people of faith, if we believe as Johnny Appleseed did that God’s love is good news for humanity, then our vocation is to share that good news in whatever ways we can given whatever sort of work fills our days. This idea is so appealing in it simplicity and practicality. It is, in fact, “good news, fresh from heaven.”

I am participating in a Patheos Book Club Roundtable on this book. To read other reviews, click here.