Patheos has invited bloggers to reflect this month on what we are grateful for in our spiritual lives. As I was considering that focus, I was also contemplating a question I received from a reader via email about what denominations I might recommend for a committed Christian who tends to lean left on political and social issues. I am no denominational expert or church sociologist, so the only way I know how to answer that last question is to share how I have found a home in the Episcopal Church. I decided to bring these two strains of thought together—gratitude for what has influenced my spiritual life, finding a church/denomination where I am at home—into a three-part blog series on “Why I am Grateful to Be an Episcopalian.” Parts 1 and 2 are short versions of my spiritual autobiography, explaining how I started out as an Episcopalian, tried some other things, and ended up back in the Episcopal Church. Part 3 will more directly answer the question of why I am grateful to be an Episcopalian.

The short answer to why I’m an Episcopalian is that I was raised in the Episcopal Church, because my father is an ordained Episcopal priest. In my heavily Catholic peer group growing up, telling people that my father was a priest earned perplexed, slightly worried glances. I find that today, in the evangelical-rich Christian milieu in which I write, telling people that I am an Episcopalian earns similarly perplexed, occasionally worried responses.

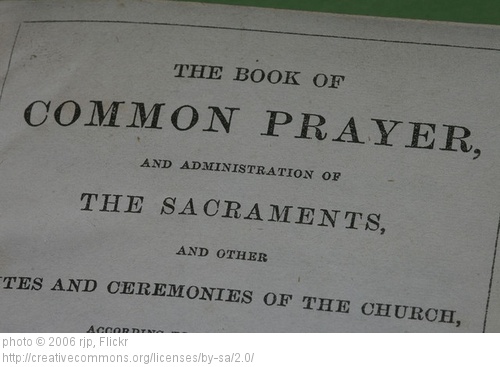

I spent enough years immersed in evangelicalism (in college) to know that Episcopalians are often not assumed to be “Christians” the way evangelicals are Christians. Our ready-made, decidedly unspontaneous prayers, our focus on potlucks and food pantries rather than “Do you know Jesus?” evangelism, our reputation as establishment churches full of folk more concerned about their investment portfolios and the whereabouts of their next drink than the state of their eternal souls (surely you’ve heard that old joke, “Wherever there are four Episcopalians, you’re sure to find a fifth”)—all of these conspire to make Episcopalians, and members of other traditional mainline churches, suspect in evangelical eyes. In my college milieu, Episcopalians weren’t as suspect as the Catholics, who were the subject of glossy paperbacks blaring questions such as, “Can you be Catholic and Christian?!” But we were suspect enough.

After college, I joined a small urban coffee-house church that was much more liberal socially and politically than my college fellowship, but equally dubious of mainliners. In part, this was because our nontraditional worship and structure (we had no clergy, for example) attracted those who had been deeply hurt or turned off in some way by mainline churches. But the suspicion also spilled over into the same territory as that of conservative evangelicals—suspicion that the saying of the same old rote prayers every week in old buildings where people dressed up for Sunday worship could not possibly embody a vibrant, personal, life- and culture-changing faith.

To some extent, that is probably true. Traditional mainline churches are bound to attract traditional, middle-of-the-road folk. They can be attractive places for people who are more comfortable repeating a memorized confession than dwelling at length on their individual and corporate sins, much less on what a young Jew’s tortured execution on a cross might have to do with those sins; for people who aren’t sure they really believe everything in the Nicene Creed and so stand silently, anonymously, while the rest of the congregation says it, confident that in this buttoned-up place, there will be no altar calls, no in-your-face demands to say once and for all if you accept Jesus as your personal lord and savior.

To some extent, that is probably true. Traditional mainline churches are bound to attract traditional, middle-of-the-road folk. They can be attractive places for people who are more comfortable repeating a memorized confession than dwelling at length on their individual and corporate sins, much less on what a young Jew’s tortured execution on a cross might have to do with those sins; for people who aren’t sure they really believe everything in the Nicene Creed and so stand silently, anonymously, while the rest of the congregation says it, confident that in this buttoned-up place, there will be no altar calls, no in-your-face demands to say once and for all if you accept Jesus as your personal lord and savior.

I admit that, during my evangelical college years, I saw the Episcopal Church of my childhood as an overly comfortable, non-demanding place. When a personal crisis of isolation and identity forced me to decide what, after all, I really believed, and led me to cling to Gospel promises (along with a new Christian social group), I found the more open, casual evangelical vibe to be just what I needed. I needed to talk about Jesus and what he had to do with MY life. I needed people to point me to the wisdom of scripture. I needed to pray spontaneous, heartfelt prayers, holding hands in a circle with my new friends. I needed to sing and clap in praise.

I remember thinking, “Why am I learning all of this stuff about Jesus only now, despite spending my entire life going to church?” It was my father who pointed out the obvious, which was that the churches we attended for my entire childhood, the hymns and anthems I sang with the church choir, the scriptures read from the lectern, the sermons given from the pulpit—all of these articulated the same truths that I was now discovering. That God loves the world, his creation. That God loves me. That Jesus Christ offers humanity’s, and my, best hope of redemption and renewal. That we all sin and fall short of what God wants for us, and God always stands ready to pick us up, help us dust ourselves off, and continue to feed us on the journey to wholeness of self and love for others. I had heard these truths my whole life in church, but it took a crisis to get me to really ponder them. That I ultimately heard these truths in an evangelical context didn’t mean that evangelicalism held the keys to the kingdom and Episcopalianism was a sham. It just meant that God is very creative and uses whatever means necessary to reach out to those he loves.

After college, I spent nine years in that little coffee-house church in D.C., where I met and married my husband. He grew up in the Methodist church and, like me, had a central and enriching college faith experience through the Baptist Student Union. So in 1999, we moved from D.C. to Connecticut without a commitment to a particular denomination. We began a process of “church shopping” that helped us refine and define what exactly we were—and weren’t—looking for in a church.

Come back tomorrow for Part 2!