Before buying the house we live in now, we lived in a tiny five-room ranch house. When we bought that house, we had one child and expected to end up with two. Instead we ended up with three, which is what eventually sent us out looking for larger quarters.

I brought two of my three babies home to that little ranch house. From that house, our oldest daughter first boarded the bus to her public preschool across town, and later entered the bigger world of kindergarten and elementary school. I wrote much of my book in that house, sitting at the office armoire in the corner of our bedroom while my oldest daughter was at preschool and my second daughter napped. When we moved in, the house had a completely blank yard—just grass and a couple of nondescript trees. We planted shrubs and ornamental maples and dogwoods and perennials.

Though we only lived in our little ranch house for about four years, it was a momentous four years for us. In that house, we grew into a family.

Yesterday, I was driving along on the main street that parallels the road on which our former ranch house sits. As I always do, I peered quickly between two houses on the main road to catch a glimpse of our old backyard, with its knobby linden tree that some former owner had pruned into an odd shape, the gardens that we planted, and the grass where my children romped under the sprinkler on long-ago summer days.

This time, as I took a quick peek at our former home, my breath caught in my throat. For there, sitting on the concrete back steps, just outside the kitchen door, was a little girl. I couldn’t take in much detail, seeing as I was driving 30 miles an hour at the time. But I clearly saw her blonde curls and her bright pink coat. She looked to be around three years old. Glimpsing her halo of blonde hair but unable to register her facial features, I felt that I was seeing my own Leah. Leah who is now 13 years old and taller than me, but who sat many times on that same back step outside that same kitchen door when she was three years old, with her blonde curls and her pink winter coat.

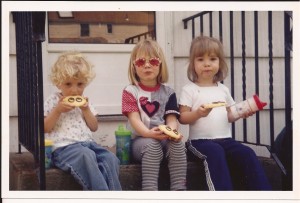

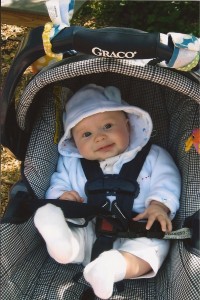

As I always am when confronted suddenly with a vision of my children as babies and toddlers—in a photograph or a memory prompted by conversation or some object associated with their tiny selves—I was hit in the chest with grief. The grief of understanding that those small ones with whom I used to spend nearly every hour of every day, those cheeks and hands and feet and bottoms and limbs that were once so familiar because of how much time I spent holding and dressing and washing and stroking and gazing at them, are gone. Lost. I can look at a picture, of course, and recognize the children whom I love today in the chubbier-faced, blonder, less articulate but more smiley little ones who gaze out from those photos. But even though I know I paid attention, made a point of trying to memorize how they sounded and looked and felt, their quirky turns of phrase and habits, I struggle to recall any of it in more than a superficial way.

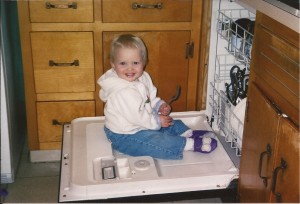

Routines that were once daily or hourly have been replaced by other routines. While I can recall a few of each child’s idiosyncrasies—how Ben called Christmas lights “lee loo lights” (as all of us still do today), how we learned to never tell Leah of our plans ahead of time because she would freak out if plans changed, how Meg would climb onto the dishwasher door as we tried to load the dirty plates after supper—I know that there are dozens more funny words, personality quirks, and amusing behaviors that used to be part of our daily fabric and are now disintegrated into dust.

This knowledge is painful because I know there is simply nothing to be done to remedy or avoid such loss of memory, and of the children we once knew as intimately as we know ourselves (maybe more so?), as they grow into the children we know today. I know now that paying close attention doesn’t prevent this loss. I know that photos and videos can only help a little bit (and that gazing at those infant faces and listening to those high-pitched toddler voices on video can sometimes make the loss even sharper).

And of course, I know that this loss of our children’s earliest years is not merely unavoidable, but necessary if we are among those luckiest of parents whose children grow into awkward adolescence and eventually adulthood mostly happy and well. I know that grieving the fact that I once had a curly blonde-haired three-year-old daughter with a sing-song voice and skinny little arms and legs and a sharp mind that didn’t miss a trick, but who is still with me today in the form of a gangly teenager whose curls have darkened and who now turns her sharp mind to math and science and word games with her friends, is an essential and fortunate grief, one for which I should be, and am, grateful. I am grieving something precious that has grown into something equally precious, grieving change rather than absolute loss.

I do miss that little blonde girl on the back steps, though. And the other little blonde girl who came along later, who would stand at the kitchen door looking out at the backyard while I cleaned up the lunch mess. And the little blonde boy who spent hours sitting in that kitchen in his bouncy chair, breaking into a grin every time one of his bustling family members—or anyone else for that matter—would happen into his line of vision.

I also miss the person I was in that little ranch house. The young mother. The mother who weighed 10 pounds less and whose arthritic knees didn’t hurt quite so much. The mother who didn’t see her children’s needs as a distraction from her true calling, but as the calling itself.

In her beautiful book Love and Salt: A Spiritual Friendship Shared in Letters, Jessica Griffith writes to her friend (and co-author) Amy Andrews about time and grief:

Chronos is the measurable passage of time. It’s chronology, the time “which changes things, makes them grow older, wears them out.” [quote from Madeleine L’Engle] Kairos is the immeasurable moment, an opening or a breakthrough, an intersection with eternity; God’s time….[M]aybe this tug [of kairos against chronos] is what has driven us to seek God. This obsession with time has become only more acute with motherhood. I can’t experience a moment without mourning its passing.

Later, Griffith writes:

This is the first concept of heaven that has filled me with anticipation rather than dread. That I may remember and know my life and its loves in the next life, but that all the pain of existence will be made whole at last. We will not forget or long for the past; we will have it, perfected.

My glimpse of the little blonde girl on the back step of the home that is no longer ours certainly felt like a clash of some kind, between past and present, between gratitude and grief for what is and was. It also, for just a split second, brought me back to the time when it was my little blonde girl who sat on that back step, in a way that felt more immediate than memory. Calling that a glimpse of heaven, of life as it was and is and is to come, feels just about right.

(I will post a longer discussion of Love and Salt nextweek as part of the Patheos Book Club.)