Just before Christmas, the American Humanist Association ran bus ads with the slogan ‘Just be good for goodness sake’.

Just before Christmas, the American Humanist Association ran bus ads with the slogan ‘Just be good for goodness sake’.

Yeah right.

From an evolutionary standpoint, pure selfless altruism – doing something that costs you but only benefits someone else – doesn’t make sense. Altruism is usually explained by kinship, or because it enhances reputation, or because it avoids punishment. People are good because they get something out of it.

But what about anonymous encounters? Say if I were to meet you in a dark alleyway. I’m never going to meet you again, and nobody will ever know what I did. Evolution says that the sensible thing for me to do is to mug you and steal your money.

Of course, sometimes that’s exactly what does happen (not with me, I hasten to add!). But usually it doesn’t. Explaining this so-called ‘pure altruism’ is tricky. Often, it’s explained as some kind of aberration – in the real world you can’t ever be sure that what you do is truly anonymous, so we are driven to err on the side of altruism.

But maybe there is a better explanation. Maybe co-operation is a successful strategy even when individual transactions are anonymous. There’s a new study that sheds light on how that might happen.

What the researchers (two social scientists based in Zurich) did was run a computer simulation based on the classic ‘prisoner’s dilemma’. This is basically a two-way gambling game where co-operation by both players gives the greatest rewards, but the worst outcome is if you co-operate and the other guy defects. If it’s just an anonymous two player game, then the best strategy is always to defect. Trying to co-operate just means you get taken for a sucker.

So what they did was broaden it out a bit. They stuck their computer ‘agents’, who played the game, in a grid with vacant squares. The agents could either be co-operators or defectors in trades with next-door agents, and they could swap their role either by copying those around them or by random chance.

Also – and crucially – the agents could look around their neighbourhood and see if there were any vacant spots where they might get a better deal. If there were, they could move. Now, the agents all had amnesia – no memory of how the other agents had behaved. But they could tell if neighbourhoods were filled with co-operators or defectors. And look what happened.

Now, the agents all had amnesia – no memory of how the other agents had behaved. But they could tell if neighbourhoods were filled with co-operators or defectors. And look what happened.

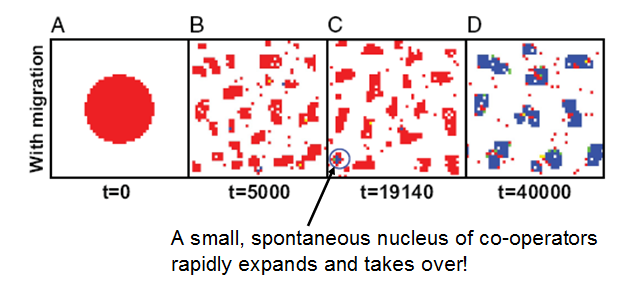

The figure shows the results of one experiment that started off with a group of pure defectors (in red). Time passed and the agents moved around. Some individuals tried out the co-operate strategy, but they were rapidly taken advantage of, and so turned back to being defectors.

But then, and purely by chance, a small group of co-operators happened to come together. And they were so successful that the other agents started to copy them. Sure, defectors tried to invade the co-operating groups, but whenever they did that the group collapsed and the agents migrated somewhere better. What they ended up with is a dynamic pattern of groups of co-operators with parasitic defectors living on the margins.

They ran the simulations with added noise – to simulate the reality that real-life decisions are often imperfect – and found the same thing. It’s a pretty stable result. Here’s what they conclude:

Our results help to explain why cooperation can be frequent even if individuals would behave selfishly in the vast majority of interactions. Although one may think that migration would weaken social ties and cooperation, there is another side of it that helps to establish cooperation in the first place, without the need to modify the payoff structure. We suggest that, besides the ability for strategic interactions and learning, the ability to move has played a crucial role for the evolution of large-scale cooperation and social behavior.

In other words, the implication is that if we can choose the kind of neighbourhood we live in, then even pure altruism can be explained by simple evolutionary dynamics. Of course, the other explanations of altruism probably still dominate. But this study seems to go some way to explaining why we are good even when we don’t seem to be getting anything obvious out of it.

![]() D. Helbing, W. Yu (2009). The outbreak of cooperation among success-driven individuals under noisy conditions Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0811503106

D. Helbing, W. Yu (2009). The outbreak of cooperation among success-driven individuals under noisy conditions Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0811503106