Take 20 believers and 20 non-believers. Stick them in an MRI machine (you may need an NIH grant for this part) and fire 60 statements at them while you scan their brains. Questions like “God’s will guides my acts” and “God cares about the world’s welfare” should do nicely. Get them to deny those those statements while you do it. Then stand back and see which bits of their brains light up in the believers compared with the non-believers.

Take 20 believers and 20 non-believers. Stick them in an MRI machine (you may need an NIH grant for this part) and fire 60 statements at them while you scan their brains. Questions like “God’s will guides my acts” and “God cares about the world’s welfare” should do nicely. Get them to deny those those statements while you do it. Then stand back and see which bits of their brains light up in the believers compared with the non-believers.

Will it be the areas related to logical processing? Will it be linguistic areas, or higher emotional functions, or perhaps those areas related to experiential knowledge?

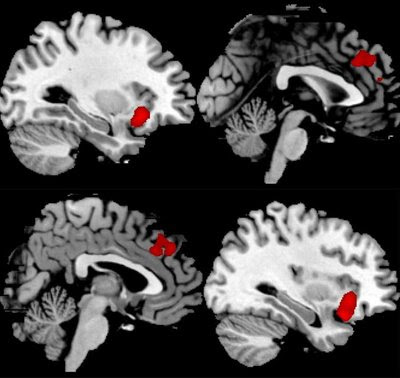

Nope. It’s the bits related to deep-seated emotional responses to cognitive conflicts (the anterior insulae), as well as higher-order cognitive conflict (the middle cingulate gyri). They’re the bits marked in red in the top picture.

What does this prove? Well not a lot, I suppose. That religious people experience emotional conflicts when denying God is not a great surprise, but it’s nice to see it in action.

Want to see something else rather cool? I bet you’re wondering what the difference was between the two sets of brains when they weren’t denying God.

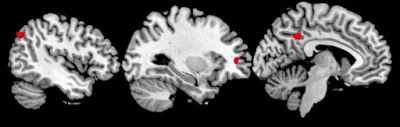

When your average, middle-aged, right-handed, US believer ponders God, three tiny bits of the brain light up (in addition to the bits that non-believers use). According to the study authors, these bits of the brain might be to do with episodic memory retrieval and imagery and greater effort in representing the meaning of the statements.

When your average, middle-aged, right-handed, US believer ponders God, three tiny bits of the brain light up (in addition to the bits that non-believers use). According to the study authors, these bits of the brain might be to do with episodic memory retrieval and imagery and greater effort in representing the meaning of the statements.

OK, now to be fair these two findings were not actually what the study was about. What the researchers (led by Jordan Grafman ) really set out to do was to find out what are the core religious experiences, and to determine which bits of the brain are responsible for processing or generating them.

What they came up with is a four-factor model of religion (God’s involvement, God’s anger/emotion, Doctrinal knowledge, Experiential knowledge). And lo! They found that each of these was associated with a different kind of brain activity. Crucially, each of these patterns of activity could be linked to standard brain processes linked to normal, non-religious functions.

Statements based on God’s involvement provoked activity in brain regions associated with understanding intent. Statements of God’s emotions stimulated regions responsible for classifying emotions and relating observed actions to oneself. And knowledge-based statements activated linguistic processing centres. Pretty much what you’d expect.

There’s been a lot of press interest in this study, most of it sensationalist (if you can believe that). They haven’t found a God spot, or even god spots. They haven’t shown that religion is just a by-product of evolution.

What they have shown is that we think about religious concepts in pretty much the same way we think about other concepts. Which is nice, but not as much fun as the results I put up top!

(Many thanks to )

____________________________________________________________________

![]() D. Kapogiannis, A. K. Barbey, M. Su, G. Zamboni, F. Krueger, J. Grafman (2009). Cognitive and neural foundations of religious belief Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0811717106

D. Kapogiannis, A. K. Barbey, M. Su, G. Zamboni, F. Krueger, J. Grafman (2009). Cognitive and neural foundations of religious belief Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0811717106