Here’s a new analysis of the 2007 Pew Survey on the USA Religious landscape, confirming some very old news: women are more religious than men on virtually every measure. And here’s a write up of it that’s rather more surprising:

Rodney Stark, a professor of sociology and comparative religion at the University of Washington, flips the question around: Why are men less religious?

“Studies of biochemistry imply that both male irreligiousness and male lawlessness are rooted in the fact that far more males than females have an underdeveloped ability to inhibit their impulses, especially those involving immediate gratification and thrills,” Stark argued in a 2002 paper in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion.

The upshot is that some men are shortsighted and don’t think ahead, Stark said, and so “going to prison or going to hell just doesn’t matter to these men.”

Now hold on a minute here! That’s a pretty bold claim, and needs some pretty powerful evidence to back it up. Unfortunately the evidence is circumstantial. What’s worse, recent studies have proved Stark to be just plain wrong.

Let’s back up a moment to see where Stark is coming from. In 2002 he co-wrote a study with Alan Miller (Hokkaido University) that looked at survey evidence on religion from around the world. What they showed was that women are more religious than men in every society, and the gap in religiousness was greater in more liberal societies than in more traditional ones. They also found some evidence linking a bigger gap to religions with a greater fixation on reward and punishment in the after life.

Given that men are more likely to take risks than women, they proposed that men are less religious because they are willing to take a gamble on there not being an afterlife. Classic Pascal’s Wager, in other words.

In 2007 sociologists Jeremy Freese (Harvard) and James Montgomery (University of Wisconsin-Madison) ripped that argument to shreds.

Never mind the fact that Pascal’s Wager is a pretty dodgy to start with, Stark’s argument assumes that everyone makes the same risk assessment. Everyone has the same answer to the question: “What’s the odds of going to hell if I don’t go to Church today?” It’s just that men are prepared to take that risk, whereas women aren’t. Technically, this is called risk preference.

Whereas what in fact probably happens is that men judge the risk to be lower. I don’t believe, therefore I judge the risk of going to hell to be pretty much zero, therefore I don’t go the church. This is called risk assessment, and has nothing to do with men being more prepared to take risk. But even going along with Stark’s assumptions, Freese & Montgomery show that his argument is bogus. Stark frames it in economic terms, and so they use a standard economic model to test it. Here’s the choices open to you. R is reward, C is cost (i.e. all the time spent in Church when you could’ve been doing something else), and P is punishment.

But even going along with Stark’s assumptions, Freese & Montgomery show that his argument is bogus. Stark frames it in economic terms, and so they use a standard economic model to test it. Here’s the choices open to you. R is reward, C is cost (i.e. all the time spent in Church when you could’ve been doing something else), and P is punishment.

What they show is that risk-takers should be more motivated by the idea of heaven than of hell. And the opposite applies to the risk averse – the idea of hell should put the fear of God into them!

In other words, if Pascal’s wager was important, and if women are more risk averse, you should only find more women than men in the group of people who believe in hell but not in heaven. In fact, almost no-one believes only in hell. And anyway, when Freese & Montgomery looked at data from the international World Values Survey, they found that women were more religious than men whether or not they believed in heaven or hell (or both). Pascal’s wager makes no difference.

But so far this is all very theoretical – and economic theory at that (which doesn’t have a great reputation right now!). So here’s some hard data from Louise Roth at the University of Arizona. She took a look at both international and US survey statistics, and found pretty much the same thing wherever she looked.

But so far this is all very theoretical – and economic theory at that (which doesn’t have a great reputation right now!). So here’s some hard data from Louise Roth at the University of Arizona. She took a look at both international and US survey statistics, and found pretty much the same thing wherever she looked.

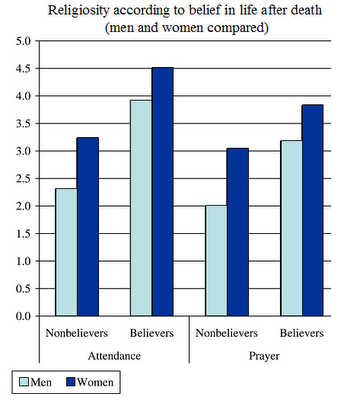

The data I’ve pulled out are from the US General Social Survey. They show church attendance and prayer according to whether people believe in the afterlife or not. What you need to look at here is the gap between the ‘men’ column and the ‘women’ column.

As expected, there is a gap – women are more religious than men. But the gap is actually smaller among those who believe in an afterlife!

These numbers are the exact opposite of what Stark’s theory predicts. Far from being unconcerned with life after death, it seems that the best way to get men involved in religion is to promise them life eternal!

If it’s not Pascal’s wager, then must be something else that’s attracting women to religion. But what? I’ve been looking at that too – with a bit of luck I’ll cover it in my next post.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

![]() Jeremy Freese, James Montgomery (2007). The Devil Made Her Do It: Evaluating Risk Preference as an Explanation of Sex Differences in Religiousness. Advances in Group Processes: The Social Psychology of Gender. Oxford, Elsevier, 187-230

Jeremy Freese, James Montgomery (2007). The Devil Made Her Do It: Evaluating Risk Preference as an Explanation of Sex Differences in Religiousness. Advances in Group Processes: The Social Psychology of Gender. Oxford, Elsevier, 187-230

Louise Marie Roth, & Jeffrey C. Kroll (2007). Risky Business: Assessing Risk Preference Explanations for Gender Differences in Religiosity American Sociological Review, 27 (2), 205-220