In the last post, I reported on a study into whether religious people are more likely to support the Supreme Court to judge matters of right and wrong. Apparently they are. This is in line with the well-known fact that religious people are more likely to have authoritarian natures.

But it doesn’t necessarily follow that religious people are more likely to obey authorities if those authorities are religious. There’s some good evidence of this from studies of physicians. The most recent has just been published in the journal Academic Medicine.

The study lead was Farr Curlin, from the University of Chicago. Back in 2007 he published a survey which asked US physicians whether they are obliged to refer patients if the patients want a treatment to which they are entitled but which the physician objects to on personal ethical grounds. Abortion is a classic example.

Now, the rules on this are in fact murky. But, as Bernard Dickens, Professor of Health Law and Policy at the University of Toronto, wrote in a paper earlier this year:

The right to conscientious objection is founded on human rights to act according to individuals’ religious and other conscience. Domestic and international human rights laws recognize such entitlements. Healthcare providers cannot be discriminated against, for instance in employment, on the basis of their beliefs. They are required, however, to be equally respectful of rights to conscience of patients and potential patients. They cannot invoke their human rights to violate the human rights of others. There are legal limits to conscientious objection. Laws in some jurisdictions unethically abuse religious conscience by granting excessive rights to refuse care. In general, healthcare providers owe duties of care to patients that may conflict with their refusal of care on grounds of conscience. The reconciliation of patients’ rights to care and providers’ rights of conscientious objection is in the duty of objectors in good faith to refer their patients to reasonably accessible providers who are known not to object.

In other words, if s doctor refuses to provide a service on moral grounds, they have an obligation to refer.

What Curlin found was widespread disagreement with this basic principle among the religious. Nearly half of all physicians with high ‘intrinsic religiosity‘ rejected it, as did 40% of those who went to church twice a month or more. It was rejected by less than 20% of non-religious physicians. Scroll forward to 2009, and Curlin has done a follow up survey (again in the USA). This time, he specifically asked doctors whether they agreed or disagreed witht he statement “Sometimes physicians have a professional ethical obligation to provide medical services even if they personally believe it would be morally wrong to do so.”

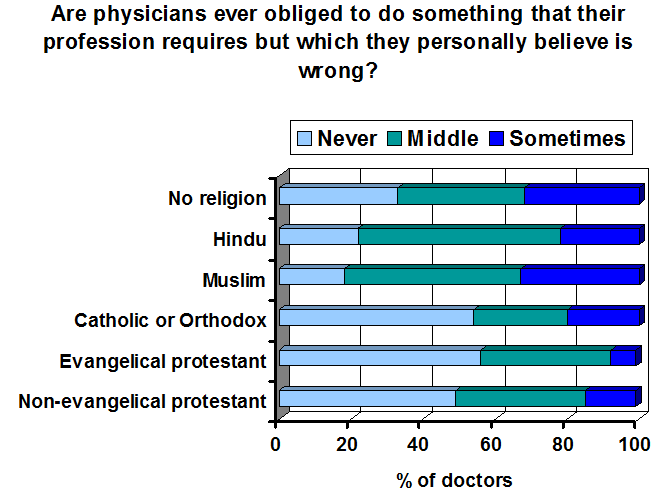

Scroll forward to 2009, and Curlin has done a follow up survey (again in the USA). This time, he specifically asked doctors whether they agreed or disagreed witht he statement “Sometimes physicians have a professional ethical obligation to provide medical services even if they personally believe it would be morally wrong to do so.”

The results probably aren’t quite what you’d expect.

For Christians versus atheists, there’s a clear difference. Christians were more likely to reject the idea that they have a professional obligation to provide services they find immoral.

But Hindus and Muslims were much more open to the idea. In fact they seem more open to the idea of professional obligations trumping personal reservations.

Curlin explains these differences in two ways. Firstly, in cultural terms:

The idea that physicians should never act against conscience follows from a long Western tradition, expressed in the maxim, “Let your conscience be your guide.” This tradition is rooted in part in Catholic moral theology, which says that an individual “must always obey the certain judgment of his conscience. If he were deliberately to act against it, he would condemn himself.”

To me, this doesn’t seem very likely. The atheists in his survey probably have mostly a ‘Christian culture’ heritage. And yet they accept professional obligations.

Curlin also found that immigrants are more likely to prioritise their professional obligations, and writes that:

…this finding may indicate that immigrants make a special effort to accommodate and adapt to what they perceive to be the expectations of the host culture.

It would be interesting to do this study in India, to see if the findings are different. But it might explain the atheists responses – as a minority group, they might be more inclined to see the value of having professional rules that apply to everyone.

Alternatively, it might be that the ones who have the biggest problems with the rules are the Christians. After all, the rules tend to allow medical procedures that are anathema to some religious authorities.

Atheists, on the other hand, have no rule book to follow except the commonly agreed standards of the society in which they live.

____________________________________________________________________

![]() Curlin, F., Lawrence, R., Chin, M., & Lantos, J. (2007). Religion, Conscience, and Controversial Clinical Practices New England Journal of Medicine, 356 (6), 593-600 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa065316

Curlin, F., Lawrence, R., Chin, M., & Lantos, J. (2007). Religion, Conscience, and Controversial Clinical Practices New England Journal of Medicine, 356 (6), 593-600 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa065316

Lawrence RE, & Curlin FA (2009). Physicians’ beliefs about conscience in medicine: a national survey. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 84 (9), 1276-82 PMID: 19707071

This work by Tom Rees is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License.

This work by Tom Rees is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License.