![]() It’s generally taken as fact that religion is linked to happiness – happier people are more likely to be religious, if you take into account other circumstances. There are loads of studies, of varying quality, that support this idea.

It’s generally taken as fact that religion is linked to happiness – happier people are more likely to be religious, if you take into account other circumstances. There are loads of studies, of varying quality, that support this idea.

Most people who interpret these data make a couple of assumptions that are probably not valid. Firstly, the assume that they can be generalised across cultures. However most studies are done in the USA, where being non-religious often leads to social exclusion.

They also mostly assume a linear relationship between religiosity and happiness. But Luke Galen has shown that there may well be a U-shaped relationship between religion and happiness.

In a new piece of research, Howard Meltzer (at the University of Leicester in the UK) has analyzed data from interviews with over 4,000 kids aged 11-19, their parents and their teachers. It’s a pretty good sample of Britain’s kids.

One remarkable finding was that 58% of these kids said that they had no religion at all! So in this sample, unlike samples from the USA, being non-religious is normal.

The largest religious denomination was Protestantism (14%) – but 40% of the Protestant kids said that, although they are Protestant, they know nothing about the religion. They are simply ‘culturally’ Protestant.

At the other end of the scale were the Muslim kids. Although only 3.3% of the total sample, some 60% of them said that their religious beliefs were strongly held (compared with only 20% of Christian kids).

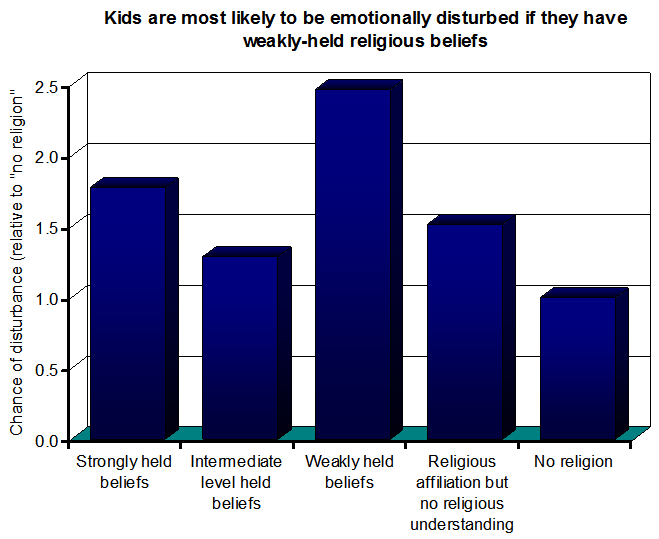

So how did the strength of religious beliefs correlate with emotional disturbances (a mixed bag of anxiety disorders and/or depression)? In order to test this, they first adjusted the data to strip out the effects of age, sex, economic status, and type of religion.

As you can see from the first figure, religious kids were, in general, more likely to report emotional disturbances – although for the most part this didn’t reach statistical significance. The effect was particularly pronounced (and statistically significant) for kids with weakly held beliefs.

As you can see from the first figure, religious kids were, in general, more likely to report emotional disturbances – although for the most part this didn’t reach statistical significance. The effect was particularly pronounced (and statistically significant) for kids with weakly held beliefs.

All this is particularly interesting given that British kids today have more emotional problems than kids did in the past. Maybe that isn’t down to loss of religion, after all – at least, not directly!

What this suggests is that kids who have been brought up religious, but have difficulties accepting religion, face conflict and guilt. According to Meltzer and colleagues:

… children expressing weakly held views may be experiencing a range of different emotions from guilt (that they do not hold the beliefs as firmly as perhaps they feel they should), ambivalence (that the beliefs are at odds with other beliefs or values they may hold), hostility (that they are expected to share the beliefs of their family and wider community but do not have the same values). In a home where the child’s views are less likely to be heard and where there are strong expectations that the religion is adhered to, the child may struggle to express themselves and internalise their emotions. This may then lead to self-harm and low mood.

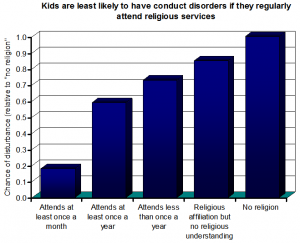

The picture is very different for conduct disorders (aggressive, disruptive, or anti-social behaviour). Religious kids were less likely to have conduct disorders, and the effect was particulty noticeable when looking at religious service attendance. There’s a nice, linear relationship – kids who go to Church, Mosque or Temple are less likely to be unruly.

The critical factor here is likely to be the social environment:

The relationship between regular attendance at religious services and the reduced likelihood of conduct disorder may be attributable to attendance at prayer meetings being associated with strong adult scrutiny and support. This probably limits the opportunity or the desire for young people to pursue antisocial behaviours. These children may also hold the views and values that come with the religion. Religious attendance can be seen as a protective factor against conduct problems via the mediating influence of prosocial peer interactions.

Loss of religion does not lead to unhappiness or other emotional problems. But loss of the social framework that religion can provide does seem to lead to conduct disturbance

The implications for secularising societies are clear. Losing religion is OK: the kids will do fine. But let’s make sure that they have a broad, engaged, mutual society to grow up in!

![]() Meltzer, H., Dogra, N., Vostanis, P., & Ford, T. (2010). Religiosity and the mental health of adolescents in Great Britain Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 1-11 DOI: 10.1080/13674676.2010.515567

Meltzer, H., Dogra, N., Vostanis, P., & Ford, T. (2010). Religiosity and the mental health of adolescents in Great Britain Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 1-11 DOI: 10.1080/13674676.2010.515567

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.