Long-time readers of this blog will know that the link between inequality and religion has a particular fascination for me. In fact, the blog started while I was doing background research into a paper I wrote in 2009, on the link between income inequality and religion in countries around the world.

The idea was first put forward in rough form in an earlier book by Pippa Norris and Ronald Ingelhart. My paper took that a modest step further, by showing that income inequality really did seem to be an independent factor helping to explain why people in some countries pray more often than in others.

But you should always treat any particular piece of research with a healthy pinch of salt. All too often, promising findings tend to evaporate on closer examination. You can only be confident that the effect is real if it holds up when you kick the tyres a bit and test out the hypothesis in different ways.

Which is why it was good to see another paper, later in 2009, which used different (more sophisticated) statistical tools to showed a link between inequality and Church attendance. That was good corroboration, because it used a different set of data and compared it with a different aspect of religion.

And now, a new paper by Nigel Barber has, to my mind, sealed the deal. One of the challenges in this kind of research comes in choosing the data. For example, you would like to look at as big a set of countries as you possibly can. The problem is that, as you move away from the wealthy democracies, the quality of the data becomes increasingly patchy.

You could use a small set of high quality data – but then the problem is that you won’t get a good sample of poorer countries. Or you could throw your net wide, and run the risk of including some dodgy data.

Ideally, you should do both, and Barber’s paper is the first to take the latter approach. He uses data on the prevalence of atheists around the world originally put together by Phil Zuckerman, who compiled it using a mixed bag of surveys and opinion polls. Not the most robust dataset, but it did mean that Barber could look at religion across a whopping 137 countries, representing every part of the globe.

The second challenge comes in figuring out whether the correlation is real, or just a coincidence due to some third factor. For example, the numbers of cars and the numbers of televisions in a country is quite well correlated – but not because cars ’cause’ televisions. In fact, they’re both a product of a third factor – wealth.

So you need to include other factors in your analysis that could reasonably also explain differences in religion between countries. Not too many though! Simply throwing variables into the pot will create spurious results. You have to choose your variables carefully, based on sound reasoning.

Barber choose to include a set of variables that were mostly different to those that have been used before. That’s useful because it effectively means looking at the problem from a fresh perspective. More kicking of the tyres.

[Geek note: Jerry Coyne wrote a review of this paper, but complained that it was a flawed study because it didn’t use multiple regression. He must’ve misread Table 2 in the paper, because that’s where the multiple regression results are presented – complete with estimates of variance inflation to check that there were no issues of multicollinearity]

So, Barber found that countries with more Muslims, a larger agricultural workforce, and more infectious diseases had fewer atheists. And countries that were once communist, had more education, and had higher taxation had more atheists.

But even after taking all this into account, those countries with higher income inequality still had fewer atheists.

That’s a remarkable result, especially when you consider that one of the main ways to reduce income inequality and its bad effects is to increase taxes. So those countries that raise taxes without fixing income inequality are still going to be more religious.

I think now we really can be pretty confident that income inequality is in itself strongly and directly related to religion. But the question is why, and how? Which way does the effect run? Does more income inequality mean more religion? Or is it that religion increases income inequality?

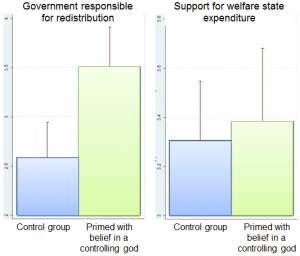

Well, long-time readers of this blog will also know that’s a big question. But there’s another new paper out that digs into this issue in a really clever way. But that’s the topic for the next post!

![]()

Barber, N. (2011). A Cross-National Test of the Uncertainty Hypothesis of Religious Belief Cross-Cultural Research, 45 (3), 318-333 DOI: 10.1177/1069397111402465

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.