In a speech just before Christmas, the British Prime Minister David Cameron declared that “We are a Christian country and we should not be afraid to say so.” He did go on to accept that it’s OK to have a different religion or even no religion at all, but even so it’s an interesting turn of phrase.

He’s a politician, of course, so it’s clear that he sees some political advantage in making the statement – but just who is he appealing to? After all, religion is pretty unimportant for most British – even the 60-70% who claim to be Christian in some way.

By happy coincidence, recent research by Ingrid Storm at Manchester University has done a neat job in clarifying why some people regard ‘Britishness’ and Christianity to be linked.

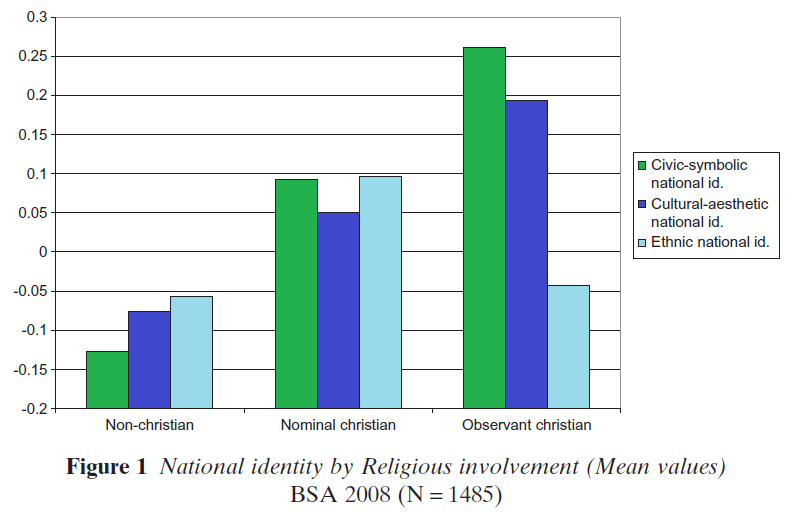

She used data from the 2008 British Social Attitudes survey of over 2,200 people, and grouped the responders according to whether they were non-Christian (a mixed bunch of other religions and also non-believers), nominally Christian (those who said they were Christian but also said they went to Church less often than monthly), and observant Christians (those who go to Church at least monthly).

The survey also asks a bunch of questions related to ideas about national identity. Storm use a statistical technique factor analysis) to group these into three categories:

- Civic-symbolic national identity (people whose sense of national identity is linked to cultural symbols, like the national anthem, sport or ceremonies).

- Cultural-aesthetic national identity (people whose sense of Britishness is triggered by thoughts of the countryside, or of music, poetry or paintings).

- Ethnic national identity (people who believe that immigration is a threat to national identity, or that a non-white person cannot be English, Welsh or Scottish).

The first thing that Storm did was to look at how nationalistic each of the three religious groups were. You’ll see from the graph that the non-Christians were the least nationalistic, and the observant Christians were the most nationalistic, at least when it cam to civic and cultural nationalism. Nominal Christians were in between.

The exception was ethnic nationalism. Neither observant Christians nor the non-Christians scored high on this measure, but the nominal Christians did.

In other word, the group most likely to see britishness through an ethnic/racial lens are the people who claim to be Christian, but who don’t actually go to church. The cultural Christians, if you will.

Storm then look at the relationship between these three kinds of nationalism and the belief that “Christianity is important for being truly British”.

The only kind of nationalism that was linked to this belief was ethnic nationalism. This link held even after controlling for factors like belief in god, authoritarianism, and the belief that Muslims do not want to fit in.

What this suggests is that the people who believe that “Christianity is important for being truly British” are also the people who define Christianity in ethnic, rather the spiritual terms. Storm says:

… thinking religion is important for nationality may be more a function of associating religion with ethnic background than of any nostalgia for the cultural heritage of religious symbols, morals and institutions associated with civic-symbolic or cultural-aesthetic national identity. In other words the more one regards immigration as a threat to national identity and thinks of race and ethnicity as important for belonging to the nation, the more one is likely to see Christianity as important for being British.

In other words, by emphasising the importance of Christianity for British identity, Cameron is appealing to the racists, rather than the religious, in his constituency.

![]()

Storm, I. (2011). Ethnic nominalism and civic religiosity: Christianity and national identity in Britain The Sociological Review, 59 (4), 828-846 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2011.02040.x

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.