Recently, the New Scientist published a special ‘God’ issue(behind pay wall) arguing that religion is natural and beneficial to society. All very interesting, but several of the articles gave quite a one-sided view of several issues (properly speaking, they were opinion pieces written by leading scientists advocating their particular view point).

Take, for example, the article by Justin Barrett, arguing that children have an innate understanding of omniscience. That’s an important question, because if we have a built-in appreciation of the thorny concept of omniscience, then this suggests that religious, and in particular Judaeo-Christian, beliefs are intuitive.

Barrett cites research by himself and others that supports this view. Broadly speaking, the idea is that young children start off by thinking that everyone has god-like powers of omniscience, and that they have to learn that mortals (like their mum) have in fact only limited knowledge.

However, there are actually just as many studies that conflict with this idea. In particular, one I covered on this blog before suggests a more complex picture. What this research, by Jonathan Lane at the University of Michigan, suggests is that in fact very young children simply assume that you know everything they know.

When they get older, they learn that others don’t know everything they know. However, crucially, they make the same assumption about God. It’s only later, when they’ve learnt about omniscience, that they can correctly ascribed these powers to God.

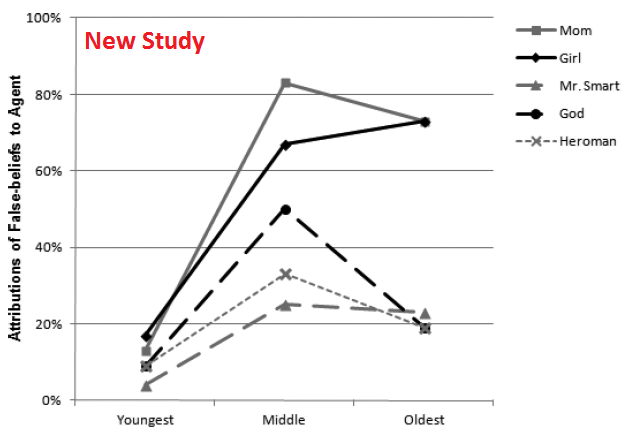

Lane’s most recent work basically replicates the original, with the interesting twist that the second study was done in children who had attended religious Protestant Christian preschools.

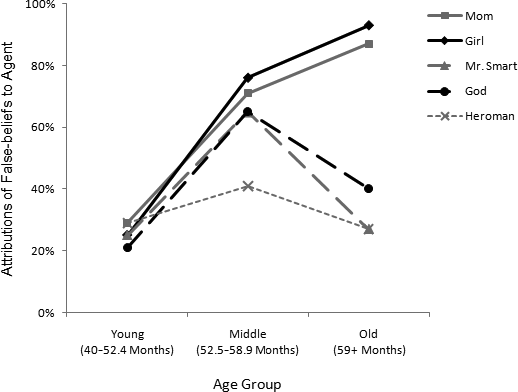

The results they got were basically the same as the first study, with one key difference (the previous study is at the top, the new one underneath). The kids who had been to a religious preschool were able to correctly say that Mr Smart can know things that you (and in fact no ordinary human) can not.

In short, they understood omniscience at an earlier age.

Intriguingly, they didn’t spontaneously attribute omniscience to God, only to ‘Mr Smart’. That’s probably because they were specifically told that Mr Smart “knows everything”, whereas they weren’t told anything about god.

What that means is that they understood the concept of omniscience, even though they hadn’t yet learned to automatically associate that idea with god.

When quizzing the children further, Lane also found that those who had more sophisticated knowledge of God’s abilities actually were more likely to understand the extraordinary powers of the other agents (Heroman, Mr Smart). It seems that the training about god they received from an early age does help them to understand the idea of extraordinary powers – but these ideas still have to be developed (they’re not innate).

Lane concludes: “…data from the current study provide compelling evidence that when children begin to understand the cognitive limitations of humans, they typically attribute those same limitations to God, and this applies even to religiously exposed children.

Only later, at around age 5 years did religiously exposed children reliably differentiate between humans’ fallible mental abilities and inaccurate mental states versus God’s less fallible abilities and states.

These results suggest that in their everyday reasoning, even children who are raised in religious settings often initially understand God’s mind as constrained and fallible, very similar to their understanding of ordinary human minds.”

So children have to develop an understanding of omniscience, even if they are raised in a religious environment. However, when raised in a religious environment, they seem to understand omniscience earlier – evidence of the importance of learning, as well as brain maturation.

![]()

Lane, J., Wellman, H., & Evans, E. (2012). Sociocultural Input Facilitates Children’s Developing Understanding of Extraordinary Minds Child Development DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01741.x This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.