Conventionally, religious affiliation is supposed to reduce the risk of suicide. In fact, the worldwide data show a rather patchy picture, probably because the effects of religion on suicide risk depend on the social context.

Conventionally, religious affiliation is supposed to reduce the risk of suicide. In fact, the worldwide data show a rather patchy picture, probably because the effects of religion on suicide risk depend on the social context.

One of the godfathers of the sociology of religion was a guy named Émile Durkheim. At the tail end of the 19th century, he reviewed the scarce statistics available to him and came to the conclusion that Protestants were less likely to commit suicide than Catholics – an effect that he put down to the sense of community that Catholics have.

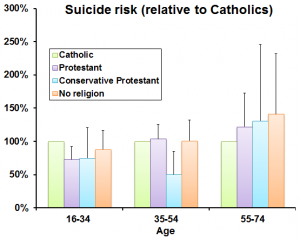

In Northern Ireland, at least, that seems no longer to be true. In fact, what the data show is that the non-religious, Protestants and Catholics all have about the same risk of suicide.

Dermot O’Reilly (Queen’s University, Belfast) and Michael Rosato (Ulster University, Derry) used census data for over a million people from 2001, which in Northern Ireland have been linked to death certificates up to 2009. So it’s a pretty comprehensive s ample.

The non-religious were substantially different from the religious – younger, less likely to be married, more likely to be divorced or separated, and also better educated and wealthier and more urban. All of these factors can contribute in different ways to suicide risk.

After taking all these factors into account, they found no difference in risk between non-religious, Catholics and Protestants.

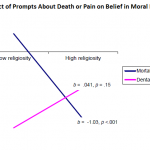

Conservative Protestants did seem to be at reduced suicide risk. As shown in the graphic, that was particularly due to sharply reduced risk in middle age.

Now, Northern Ireland is an interesting place to look at because the tribal divide between Protestants and Catholics is extremely strong. So if social identity and affiliation aspects of religion affects suicide rates, you would expect to see it here.

This study suggests that regular religious affiliation has no effect on suicide rates, and that religion itself does not protect against suicide.

But it does look like there is something going on with the conservative Protestants. But whether this is an effect of the religion, or simply reflects the nature of the people who take to conservative Protestantism, is unclear.

![]()

O’Reilly, D., & Rosato, M. (2015). Religion and the risk of suicide: longitudinal study of over 1 million people The British Journal of Psychiatry DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128694

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.