African-Americans are more sensitive to pain than Caucasian (white) Americans. That’s been shown in comparisons of much pain is experienced in illnesses such as AIDS and arthritis, after surgery, and in conditions such as lower back pain. It’s also been shown experimentally, when volunteers undergo painful experiences (like holding your hand in ice-cold water) and report how much pain they feel.

Many studies have been done to try to understand why this difference exists. One important area of research has been into differences in coping strategies.

People use a wide range of mental strategies to deal with pain. One approach is just to endure it or try to ignore it. Other approaches include exaggerating or overstating the pain (which goes by the delightful name of ‘catastrophizing), increasing activity, and praying.

Samantha Meints, a psychologist at Indiana University in the USA, and colleagues have undertaken a statistical analysis of all the studies published on this topic (a ‘meta-analysis’). They looked at data from 6,489 individuals who participated in 19 different studies, and came up with some surprising insights.

For a start, African-Americans are more likely to use coping strategies of any kind, and in particular are more likely to use prayer and catastrophizing.

In fact, the difference in the use of prayer by African-Americans versus Caucasians was almost twice as large as the difference in catastrophizing, then next most important factor.

There was one strategy used more often by Caucasians than by African-Americans: task persistence. That’s where you knuckle down and focus on the task at hand, to try to blot out the sensations of pain.

You may be thinking ‘Aha, this explains the differences in pain sensitivity!’. After all, praying to a supernatural being sounds like a pretty useless way to deal with pain, right?

But not so fast. It’s more complicated than that.

Overall, what it seems is that African-Americans are more likely to use passive, rather than active, pain coping strategies. That’s reflected in their use of passive forms of prayer, things like “I pray to God it won’t last long”.

Meints and colleagues suggest that this might be a manifestation of learned helplessness. That occurs when people come to believe that they have no control over their situation. And African-Americans might be right to think this – other studies have shown that African Americans don’t receive the same quality of pain care. As a result, the researchers say:

Black patients might conclude that no matter what they do, their pain will not be adequately treated. Consequently, they may adopt a catastrophic style of thinking about pain, while White patients who do not face such discrimination continue to seek treatment or engage in new actions to reduce pain and improve function.

On a more positive note, they also point out catastrophizing might have an important function as a social signal.

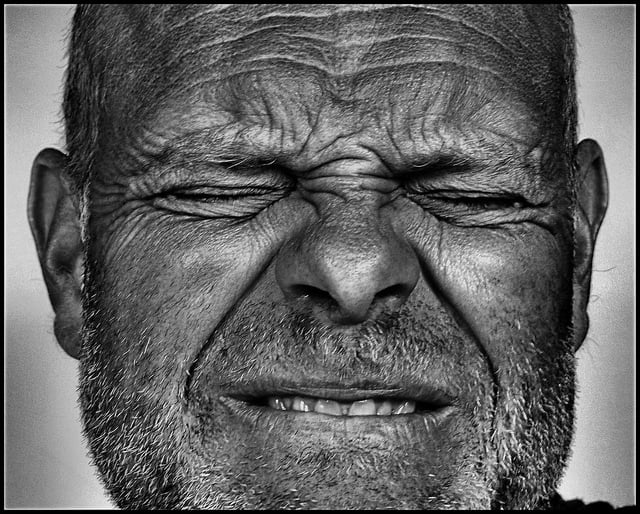

Human beings are very sensitive to pain. If you’ve ever seen an animal stoically dealing with what seems like horrific injuries, you may have marveled at the differences to humans. Psychologists have speculated that we humans holler and scream when in pain because it’s a way of signalling to friends nearby that you need help.

The researchers speculate that the close-knit nature of many African-American social communities may encourage catastrophizing about pain, rather than suffering in silence. And that “although pain catastrophizing might lead to increased pain at the intrapersonal level … it may also confer significant advantages at the interpersonal level” – by increasing social support when you need it most.

And in fact praying may be an extension of this. MRI studies have shown that devout prayer uses the same brain regions as talking to a friend or loved one.

On a final note, consider this. Pain is not simply your body’s way of telling you to avoid damage. It’s tightly bound up with the social environment you were brought up in, and the effect that has on your psychology.

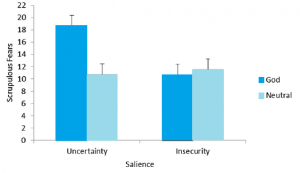

We’ve seen from other research that people who don’t feel in control of their own situation are more likely to be religious. This research suggests they’re also more likely to use poor coping strategies to deal with pain.

And one of those poor coping strategies is religion. It seems to me that the use of prayer to deal with pain is part of a broader approach to life, one that tries to deal with uncertainties and feelings of helplessness by trying to gain help and support from the supernatural.

![]()

Meints, S., Miller, M., & Hirsh, A. (2016). Differences in pain coping between Black and White Americans: A meta-analysis The Journal of Pain DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.017