…and how it might change the way we view US anti-trafficking efforts

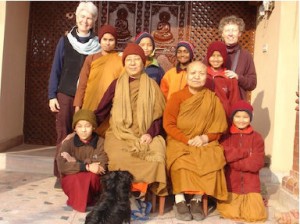

An Interview with the Venerable DhammaVijaya

Co-founder of the DhammaMoli project

Patheos has been putting the spotlight recently on human trafficking, and so far much of the discussion has been about US Evangelical Christians trying to fight it — and the critique they are receiving from certain academics, particularly about an alleged imposition of Protestant values on “rescued” “victims” (we’re using scare quotes here because both of these terms is at question, and I don’t have better replacements). There is, however, a broader range of conversations to be had about trafficking. Why not, for a moment, turn our eyes away from Christian, or even American, anti-trafficking projects, and look at what another faith tradition, in another country, is doing? The answer will of course be interesting in and of itself. But might it also inform the debate about the US approach? We’ll explore that question below. But first, let’s choose the tradition:

Buddhism ought to immediately grab our attention, if for no other reason than because authors like Kevin Bales have argued that Buddhist environments have tacitly permitted prostitution and sex slavery to flourish. Bales, founder of Free the Slaves, has written that Thai Buddhism often “shapes a culture ripe for human trafficking”. [Update, Feb. 28: I emailed Kevin Bales to make sure that I was characterizing his argument correctly. He said I hadn’t quite captured his thoughts — and has expanded in a comment below, which I encourage you to read.] In a future post, soon, we’re going to speak with someone who argues vehemently that Buddhism, properly interpreted, is completely incompatible with the practice of sex slavery. And Buddhist bloggers such as the Venerable Ani Drubgyudma have written that Buddhists should be actively engaged in stopping human trafficking. The fact that this discussion exists motivates us to find real examples of non-US Buddhist-based organizations, on the ground, fighting human trafficking. My (admittedly informal) Internet research actually did not turn up many examples. But there is one project that should be catching our eye: DhammaMoli. It may (or may not) provide a model for similar solutions around the world.

Buddhism ought to immediately grab our attention, if for no other reason than because authors like Kevin Bales have argued that Buddhist environments have tacitly permitted prostitution and sex slavery to flourish. Bales, founder of Free the Slaves, has written that Thai Buddhism often “shapes a culture ripe for human trafficking”. [Update, Feb. 28: I emailed Kevin Bales to make sure that I was characterizing his argument correctly. He said I hadn’t quite captured his thoughts — and has expanded in a comment below, which I encourage you to read.] In a future post, soon, we’re going to speak with someone who argues vehemently that Buddhism, properly interpreted, is completely incompatible with the practice of sex slavery. And Buddhist bloggers such as the Venerable Ani Drubgyudma have written that Buddhists should be actively engaged in stopping human trafficking. The fact that this discussion exists motivates us to find real examples of non-US Buddhist-based organizations, on the ground, fighting human trafficking. My (admittedly informal) Internet research actually did not turn up many examples. But there is one project that should be catching our eye: DhammaMoli. It may (or may not) provide a model for similar solutions around the world.

DhammaMoli is a small Buddhist community in Nepal that provides shelter and education to young local girls at risk of falling victim to human traffickers who might sell them to brothels in India. It was founded by two Theravadan Buddhist nuns, the Venerable DhammaVijaya and the Venerable Molini (hence the name DhammaMoli), both of whom received Ph.D.’s from a Buddhist university in Bihar, in northeast India. Theravadan Buddhism, it should be remarked, is the most prominent school practiced in Thailand, but is only one of many found in Nepal, a country in which Hinduism and Buddhism famously coexist in unique ways. Sister DhammaVijaya was ordained in Los Angeles in some 25 years ago. DhammaMoli is funded, in part, by a link-organization in Yellow Springs, Ohio.

Sister DhammaVijaya was generous enough to grant me an interview from Kathmandu to New York — not an easy task, given that communications technology at DhammaMoli is rather limited. The very talented Nepali-English interpreter Suman Kansakar helped out.

☯ ☯ ☯ ☯ ☯

Can you go into detail about how your personal spiritual practice motivates your work at Dhammamoli?

Spiritual practice supports me a lot to deal with the girls and other workers in DhammaMoli. In our practice, mindfulness is the main point, and that is why we have the confidence to tackle any situation carefully and rightly. We have no experience of motherhood, but we try our best to raise the girls with love and kindness. This is the main part of Buddhism. And we teach them Buddhist songs and meditation. They try to learn very happily and with great interest. I find the girls are very happy and satisfied at DhammaMoli.

Can you be more specific? What Buddhist thought instructs you to run a project aimed at helping stop human trafficking?

We were first exposed to the devastation brought on young girls by trafficking during our visit to Cambodia. We were invited to pray and provide teachings to HIV-infected girls in a rehabilitation center. After we came back to Nepal, we read the news of 2500 or so Nepalese girls returning from India with Hepatitis-B and HIV, and staying at an NGO called Maiti Nepal [Ed.’s note: a non-faith-based anti-trafficking organization in Kathmandu]. I, along with Sister Molini, went to visit them at the Maiti Nepal center and we were very touched by the plight of these young girls, who seem to have resigned themselves to fate. The inspiration to start DhammaMoli came to us after this visit.

As for which Buddhist ideas instruct us to run a social project like DhammaMoli: it is very difficult to explain in brief. The fundamental discourse of Buddhism is Loving and Kindness to all living beings, even your enemies. In short, Buddha has said that one should try, in whatever capacity one can, to help others — and more so, those that cannot take care of themselves. Even if you are able to save one life, that counts towards your achievement of Nirvana. [Ed.’s note: Sister DhammaVijaya says this comes from the Tripitaka Buddhist scriptures. In the classical Chinese novel Journey to the West, also called in English Monkey God, a character named Tripitaka says, “To save one life is better than to build a seven-storeyed pagoda.”]

What precisely does it mean that the girls are brought up in a “Buddhist monastic environment?” How much Buddhist doctrine and ritual do they practice while they are there?

When we started DhammaMoli, the condition of village girls in our country was very bad. We saw newspaper headlines about girls disappearing all the time from remote areas of Nepal. So we decided that we would help such girls according to Buddhist teaching. We started with four girls, at an average age of six years, from different remote regions of Nepal. We first taught them the following:

- The national language – Nepali. This is because there are many ethnic languages in Nepal, and Nepali is the language of communication all over the country.

- To be neat and clean.

- Monastic rules, regulations, and discipline.

- After that, we sent them to a public school.

- And Buddhist theory and practice.

Can you tell us more about the monastic rules and discipline? For example, do the girls meditate every day? How long?

- 5am – 6am: Wake up and getting ready time.

- 6am – 6.15am – 15 minutes meditation.

- 6.30-7.30am – Breakfast and cleanup.

- 7.45 am – Study time.

- 8.30am – Prepare for school. If no school, Buddhist teachings for about one hour.

- 9am – 4pm – School. If no school, play, read, talk, etc.

- 4.30pm – 5.00pm – Light dinner.

- 5.30pm – 6.00 pm – Chanting, 5-10 minutes meditation (school days); 30 minutes (non-school days).

- 6pm – 7.30pm – Private tutoring and homework time.

- 8.30pm – Bedtime.

Holidays – trips to local attractions. TV time (news, animal shows, cartoons).

Nepal is both a Hindu and Buddhist country, and the two religions mix together quite thoroughly there. How is Hinduism is incorporated into the life of the girls at Dhammamoli? How have parents reacted to the religious aspect of the education there?

Yes, Nepal is both a Hindu and Buddhist country. There is no influence from Hinduism in the life of girls in DhammaMoli. As they are all from remote areas of Nepal, their parents are poor and uneducated, and they don’t interfere regarding the religion. They are happy to see their children at DhammaMoli, in a clean environment, and going to school. It is with the parent’s permission that the girls come to DhammaMoli.

Do the parents get to visit? How do they react to it?

Yes, there are no restrictions on parents or relatives visiting the girls. We just ask that they visit them during the holidays or during free time. Some of the girls don’t have parents, so uncles and aunts come to visit. There is one girl from Lumbini whose mother always comes to meet us to check on her well-being when we visit Lumbini, the birthplace of Buddha. During our last visit, she requested that she wants to see her daughter, but she couldn’t herself come to Kathmandu. So we arranged to send her daughter to her mother’s place for few days’ visit.

When you are going to villages to scan for at-risk girls, what indicators do you look for? Is it usually the parents who say, here, my daughter is in a dangerous situation, please take her, or is it more that you have to identify by yourselves who is at risk, and then ask the parents if you can take the child?

We visit villages frequently, and we ask the girls how they are living and what the problems are there, often due to poverty and illiteracy. When they see us and meet us, they are happy to know that girls can also be educated, go to school, and learn new things. After the girls have shown interest, we visit their the parents and tell them about our shelter program in Kathmandu. Then the parents decide to send their daughters to stay at DhammaMoli, so that they can escape dangerous situations that arise out of poverty, such as getting married off at an early age, or being sent to cities or to India for employment, which is how most girls are tricked into prostitution.

What might the girls do when they leave DhammaMoli?

The girls are still in primary and middle school, so they have not yet graduated. Once they finish high school, we will honor their wishes at that time. They are welcome to stay at the Vihara [Ed.’s note: the Sanskrit word for Buddhist monastery, and origin of the name of the state of Bihar] or return back to their family. The girls are already learning English at our school, and we believe that education, along with Buddhist teachings, will give them the ability to make the right decision for themselves. This is something that they would not have acquired if they had been in their village.

The girls are still in primary and middle school, so they have not yet graduated. Once they finish high school, we will honor their wishes at that time. They are welcome to stay at the Vihara [Ed.’s note: the Sanskrit word for Buddhist monastery, and origin of the name of the state of Bihar] or return back to their family. The girls are already learning English at our school, and we believe that education, along with Buddhist teachings, will give them the ability to make the right decision for themselves. This is something that they would not have acquired if they had been in their village.

How do the girls, themselves, emotionally react, when they leave home and are brought to Dhammamoli?

Most of the girls that have come to DhammaMoli are young. They don’t know about anything. They are shy and quiet. They don’t know of the variety of food available, as they have grown up with only rice and lentil soup as their daily staple. They have not seen different kinds of vegetables, fruits, juices, and so forth. One of them didn’t know what a mango was. She was scared to eat a mango for the first time.

Do you know of other Buddhist-based organizations working to fight human trafficking?

We believe that there are many Buddhist organizations fighting human trafficking, but we do not know of them specifically.

A lot of trafficking originates or ends in prominently Buddhist countries (Thailand, Cambodia, Japan, etc.). Is there something in Buddhism — not necessarily in theory, but perhaps in the way it is incorrectly practiced — that enables sex trafficking, or that tacitly permits it to occur?

We have travelled in many southeast Asian countries where trafficking of girls is prevalent, and we feel that there are multiple reasons why this problem is there. The main reason is poverty, followed by illiteracy. Also, all of these countries are male-dominated societies, and a girl child is valued less, as she is seen as a burden. Also, even though some of these countries are known as Buddhist countries, the Buddhism practiced is not always pure Buddhism – it is mixed with Hinduism, Spiritualism, Tantrism, and so forth.

☯ ☯ ☯ ☯ ☯

Let’s now go back to the academic critique of Protestant values in US trafficking efforts. Certain feminist and queer theorists say that anti-trafficking organizations wrongly assume what’s best for the women and girls that they “save” (ditto on the scare quotes). Other academics worry about certain NGOs exploiting the vulnerabilities of trafficking victims to proselytize for Christianity, denying their cultural heritage.

- To be intellectually consistent, must these academics say the same things about DhammaMoli? Is it right or wrong that these Nepalese girls are brought to a safe place and then taught Buddhism from a young age?

- What about the fact that DhammaMoli doesn’t expose the girls to other Nepalese religious traditions (Hinduism, Islam, indigenous practices, and even some Christianity)? Does this constitute a similar denial of someone’s cultural heritage? When precisely is anti-trafficking about forced religion, cultural hegemony, heteronormativity or imposed “family values” — if ever?

- What is the moral difference between an American Christian bringing an at-risk girl to a church and teaching her Christianity, and a Buddhist nun bringing her to a vihara and teaching her Buddhism?

Your answers desired.

Soon I’ll be posting an American Buddhist anti-trafficking expert’s perhaps surprising opinion.

var _gaq = _gaq || []; _gaq.push(['_setAccount', 'UA-38934621-1']); _gaq.push(['_trackPageview']);

(function() { var ga = document.createElement('script'); ga.type = 'text/javascript'; ga.async = true; ga.src = ('https:' == document.location.protocol ? 'https://ssl' : 'http://www') + '.google-analytics.com/ga.js'; var s = document.getElementsByTagName('script')[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(ga, s); })();