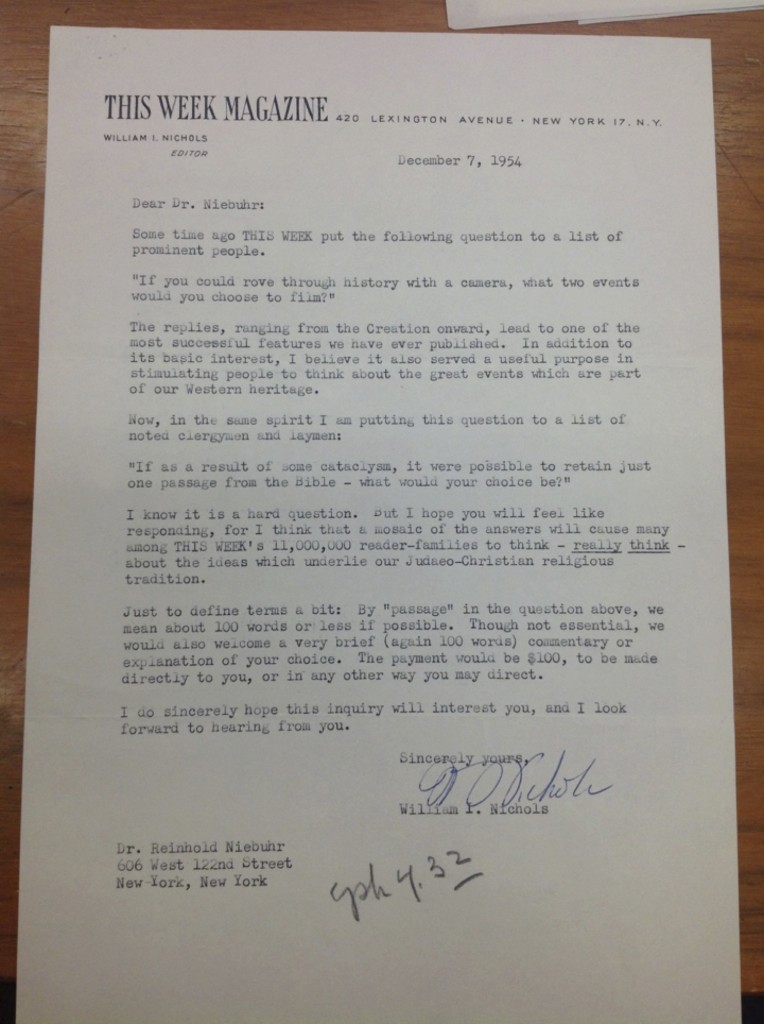

Mid-20th-century America saw several theological giants roaming the landscape, participating in public debates, and exercising a degree of social influence unrivalled by any American theologian today. One of the greatest of these giants was Reinhold Niebuhr, Professor of Applied Christianity at Union Seminary. In December of 1954, William Nichols, editor of This Week Magazine, put the following question before Dr. Niebuhr:

“If as a result of some cataclysm, it were possible to retain just one passage from the Bible – what would your choice be?”

Niebuhr’s choice, which he seems to have immediately penciled in on the letter from Mr. Nichols before writing out his full response two days later, is instructive about his theological priorities and his conception of the essence of the Christian Gospel. He responds as follows:

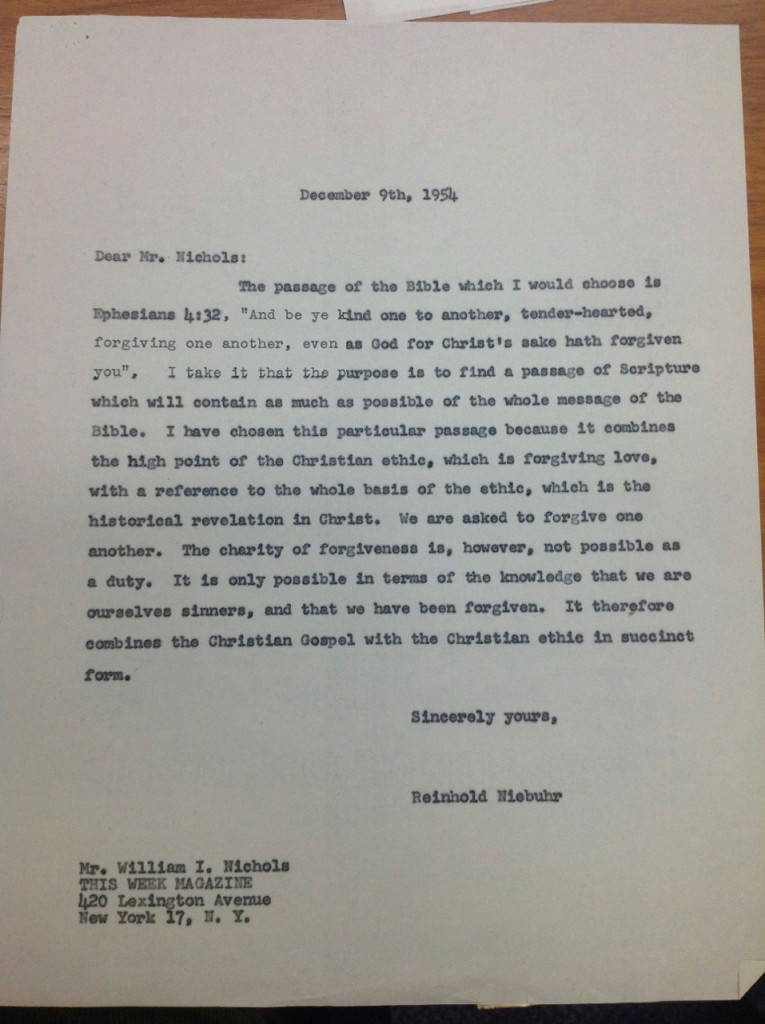

December 9th, 1954

Dear Mr. Nichols:

The passage of the Bible which I would choose is Ephesians 4:32, “And be ye kind one to another, tender-hearted, forgiving one another, even as God for Christ’s sake hath forgiven you.” I take it that the purpose is to find a passage of Scripture which will contain as much as possible of the whole message of the Bible. I have chosen this particular passage because it combines the high point of the Christian ethic, which is forgiving love, with a reference to the whole basis of the ethic, which is the historical revelation in Christ. We are asked to forgive one another. The charity of forgiveness is, however, not possible as a duty. It is only possible in terms of the knowledge that we are ourselves sinners, and that we have been forgiven. It therefore combines the Christian Gospel with the Christian ethic in succinct form.

Sincerely yours,

Reinhold Niebuhr

In Niebuhr’s view, therefore, the Christian message is twofold: a demanding ethical system, and the theological and historical grounding for that system, without which the ethical standard is impossible to achieve. This is Niebuhr’s articulation of Luther’s Law/Gospel dichotomy, which demonstrates that the Old Testament Law is not negated, but rather fulfilled by the New Testament Gospel. Christianity is not primarily an ethical system, but nor is it the occasion for antinomian licentiousness.

While this answer stands with the majority of the Christian tradition, it is also distinctively Niebuhrian in several ways. First, it recognizes the limitation on human moral performance. Niebuhr notes that mere knowledge of the moral imperative is insufficient to actually perform it. Secondly, the humble approach we must take toward our moral performance is occasioned by the reality of sin. Though Niebuhr would later mention that he regretted so frequently employing the language of sin because it entailed historical and doctrinal baggage from which he wanted to distance himself, that language is inextricably bound up with the rest of Niebuhr’s political, ethical, and theological projects.

The third way this answer is distinctively Niebuhrian (for his time and position in the mid-20th century) is his explicit emphasis on the historicity of Christ. This move is in keeping with the broad majority of Christianity and with more conservative theology that was contemporaneous with Niebuhr, an emphasis on the historicity of Christ separated Niebuhr from his earlier mainline Protestant Liberalism and which marked his shift later in life to something like Neo-Orthodoxy. Contra the post-Kantian move in Liberal Protestantism that sought to go beyond an historical faith, in Niebuhr’s view, the Christian ethical code is necessarily linked to an historical phenomenon that carries theological implications. Our forgiveness is only possible because we have been forgiven in Christ.

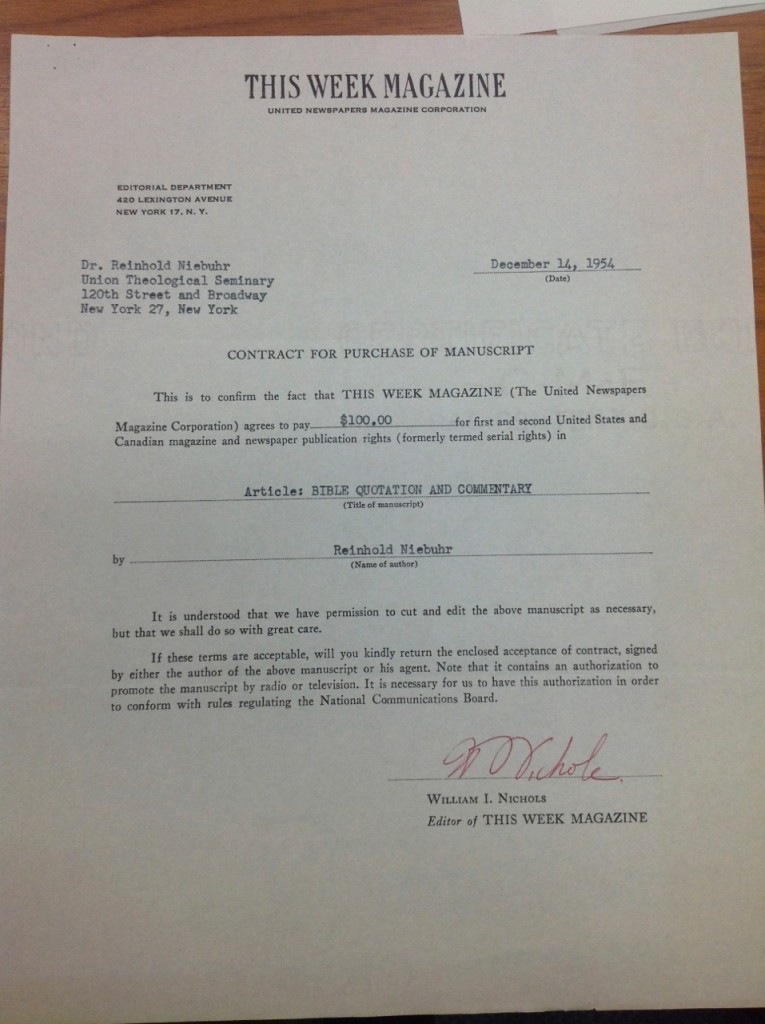

Several days later, Mr. Nichols responded with a contract and a payment for Niebuhr’s brief article. That document indicates he was paid $100.00 for his article, proving once again (much to the chagrin of theology students like myself) that even at the highest and most public level, theology has never been a very lucrative enterprise.