A couple of posts over at “Good Letters” have thoughtfully addressed art’s purpose and how it interacts with and reflects a greater reality. In the first of these pieces, Vic Sizemore responds to a recent article by Michael Chabon in the New York Review of Books. Chabon argues that the artist’s function is addressing brokenness in the world by putting back together the “‘scattered pieces of that great overturned jigsaw puzzle’ according to [the artist’s] own vision.” A creative work “is authentic only to the degree that it attempts to conceal neither the bleak facts nor the tricks employed in pulling off the presto change-o…artifice, openly expressed, is the only true ‘authenticity’ an artist can lay claim to.” Sizemore disagrees. If an artist exposes artifice and undercuts art’s ability to capture the observer, she rejects art’s capacity to reflect something greater than a single manufactured perspective. Sizemore claims art should be “an experience that you are swept up in, or at least glimpse, something larger, something utterly mysterious,” rather than a self-admittedly artificial attempt to represent a version of reality.

In a similar vein, Richard Chess’s post points out art’s limited ability to capture the largeness of life itself. Chess quotes Jon Kabat-Zinn, “Who you actually are is far bigger than the narrative you construct about who you are.” Most art is merely a single interpretation of something much larger and more complex, albeit one that can capture more of who we are, than, say, factual knowledge or logical thought. Chess concludes by noting, “I am small, though not as small as I was 713 words ago. Thank God, or art, whichever is bigger, whichever is big enough to hold what I am and what I am not.” The artist is, in some ways, imagining a divine view of the world— aspiring to an omniscient understanding of the individual.

What links these two pieces is a partial rejection of a post-modern/post-structuralist approach to creative works. While both Sizemore and Chess affirm that art involves storytelling from multiple subjective perspectives, they also imply that these perspectives actually refer to some greater reality. The artist’s hope is not that her work will comprehensively or simply creatively express a viewpoint, but rather that her (limited) piece will give the observer/reader/listener “a glimpse” into something “utterly mysterious” beyond.

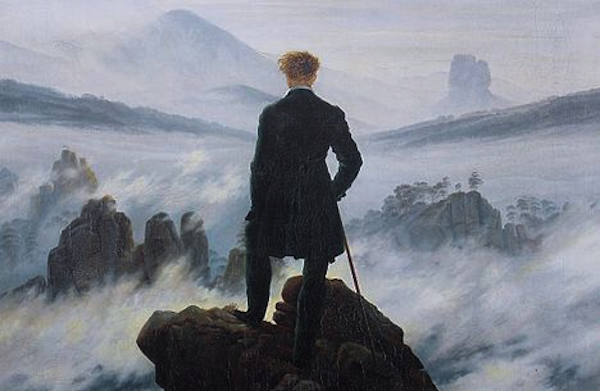

Because these two bloggers are people of faith, it would be easy to dismiss their perspectives as unrepresentative of current artistic thought. But some of these question are cropping up in non-religious circles as well. Earlier this month, Steve Neumann of “Rationally Speaking” wrote a piece on the subject of the sublime that was linked in the New York Times. Neumann references an almost Burkean sense of the sublime— something so overwhelmingly majestic that it inspires fear as well as awe—noting how romantics found the sublime in nature. He suggests that nature is less and less able to evoke a sense of the sublime, and that today, “our feeling for the sublime, if it is to happen at all, will have to come more and more from culture.” To Neumann, the sublime can be found in the cultural products of the entertainment industry – he cites the music of Led Zeppelin as an example.

It’s easy to see this logic in action. Consider recent films Les Miserables and The Great Gatsby. They are both larger-than-life motion pictures that capture an audience’s senses and emotions. Are they, as Sizemore puts it, “tipping their hand” to reveal their artifice? Not so much. And yet they are enjoyed by a catharsis-seeking general public, and are felt, in some sense, to be “true” by their audience.

But even if Neumann is onto something, the question remains of whether a concept of the sublime even should even exist in a post-modern framework. Why do we even need to encounter the sublime at all? Neumann clearly acknowledges the religious justification for this (fear of an all-powerful, all-loving God is about as sublime as it gets), though personally rejects this approach and derives his own justification from Nietzsche’s notion of Apollonian and Dionysian wills. But neither a religious nor Nietzschean approach is particularly “current.” His argument, paralleling Sizemore’s and Chess’s, begs the question of whether current philosophy of art, something like what Chabon describes, is neglecting something critical in both the authenticity and experience of art. Is a concept of art that neglects some idea of “the sublime” inadequate? Is our collective intuition poking holes in artistic post-structuralism? But I hope that a discussion is beginning.

[Image of a Caspar David Friedrich Painting From Wikipedia]